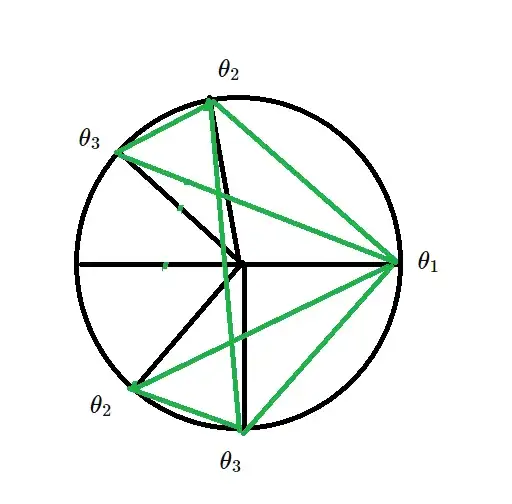

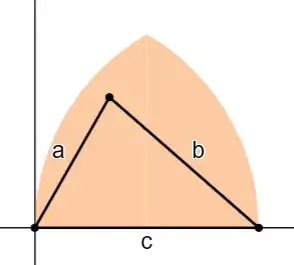

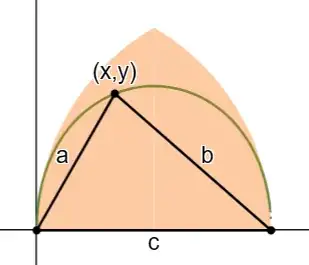

Let $(x,y,z)$ be the sides of a triangle whose vertices are uniformly random on the circumference of a circle. Experimental data using a simulation with $10^9$ trails for each tested value of $a \ge 1$ suggests that:

When $a \ge 1$ then the probability that $x^a + y^a \ge z^a$ is $P\left(x^a + y^a \ge z^a\right) = \frac{2}{3} + \frac{1}{3a^2}$, or equivalently if $x \le y \le z$. Then $P\left(x^a + y^a \ge z^a\right) = \frac{1}{a^2}$.

Can this Conjecture be proved or disproved? Related question.

Julia source code

using Random

step = 10^9

while true

a = 1

while true

f = 0

for _ in 1:step

angles = rand(3) .* 6.283185307179586

vertices_x = cos.(angles)

vertices_y = sin.(angles)

push!(vertices_x, vertices_x[1])

push!(vertices_y, vertices_y[1])

x_diff = diff(vertices_x)

y_diff = diff(vertices_y)

side_lengths = sqrt.(x_diff.^2 .+ y_diff.^2)

x, y, z = side_lengths

if x^a +y^a >= z^a

f += 1

end

end

prob = f/step

println((a, prob, prob / (2/3*(1 + 1/2/a^2))))

a = round(a + 0.1, digits=10)

end

end