Note that $g(x) = 1-x $ and $h(x) = \frac{1}{1-x}$ generate a subgroup $G$ of the Möbius group $\mathrm{Aut}(\hat{\mathbb{C}})$ that is isomorphic to $S_3$ via the relations:

$$ g^{2} = \mathrm{id}, \qquad h^{3} = \mathrm{id}, \qquad ghgh = \mathrm{id} $$

Note that $G$ also contains $h(g(x)) = \frac{1}{x}$ and that $G$ is also generated by $g$ and $hg$, which explains why $G$ is related to OP's question.

Now define $f(x)$ by

$$ f(x) := \sum_{\sigma \in G} \frac{\sigma(x)(\sigma(x) + 1)}{2}. \tag{1} $$

Then clearly $f(\tau(x)) = f(x)$ for any $\tau \in G$. Moreover, it turns out that this $f(x)$ is precisely what OP asked:

$$ f(x) = \frac{(x^2-x+1)^3}{x^2 (x-1)^2}. $$

Here is a possible explanation for the choice of $f(x)$. Consider the region

$$ U = \{ z \in \mathbb{C} : |z| < 1 \text{ and } |1-z| < 1 \text{ and } \operatorname{Im}(z) > 0 \}. $$

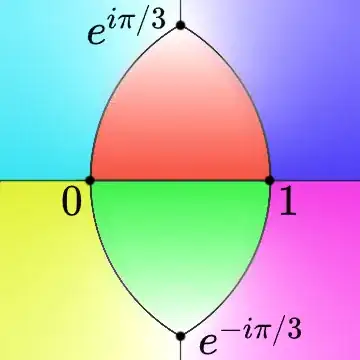

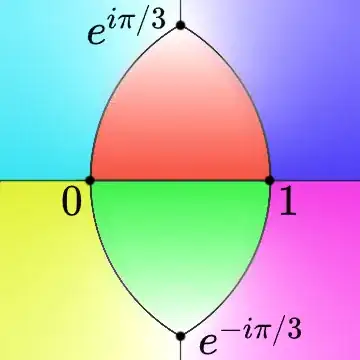

This $U$ corresponds to reddish region in the figure below:

Then $\sigma(\overline{U})$ for $\sigma \in G$ forms a non-overlapping division of the Riemann sphere $\hat{\mathbb{C}}$, each of which corresponding one of the six colored regions in the figure above.

Now, as the figure suggests, the points $e^{\pm i\pi/3}$ play special roles, in that $\sigma(e^{\pm i\pi/3}) = e^{i\pi/3}$ or $e^{-i\pi/3}$ for each $\sigma \in G$. In fact,

- exactly three elements of $G$ maps $e^{i\pi/3}$ to $e^{i\pi/3}$, and

- the remaining three maps $e^{i\pi/3}$ to $e^{-i\pi/3}$.

This tells that

$$ \sum_{\sigma \in G} \sigma(e^{i\pi/3})^2 = 3(e^{i\pi/3} + e^{-i\pi/3}) = -3. $$

This and the identity

$$ \sum_{\sigma \in G} \sigma(x) = \frac{1}{2} \left[ \sum_{\sigma \in G} \sigma(x) + \sum_{\sigma \in G} g(\sigma(x)) \right] = 3 $$

together, we know that $f(x)$ has the factor $x^2 - x + 1$. Moreover, since the figure above tells that three regions meet at each of $e^{\pm i\pi/3}$, it is not unreasonable to expect that $f(x)$ contains multiple copies of $x^2 - x + 1$.

Although I don't have enough expertise to pursue this direction, I believe Artin had certain understanding on this kind of topic when he designed the function $f(x)$.