Consider the following linear matrix inequality (LMI) feasibility problem $$ \begin{aligned} \textrm{find} \quad & X \\ \textrm{s.t.} \quad & X \succ 0 \\ \quad & F(X) \prec Q \end{aligned} \tag{1} $$ where $F$ is linear in $X$ and $Q \succeq 0$. I'm trying to solve this feasibility problem using an LMI solver, but the solver only accepts semi-definiteness constraints, and not definiteness constraints as given in $(1)$. How can I convert this feasibility problem into one with only semi-definiteness constraints? Note that this question is a generalization of this one, where the special case when $F(X) = A^T X + XA$ and $Q = 0$ was considered.

1 Answers

We provide a proof that the feasibility problem in $(1)$ is equivalent to the feasibility problem $$ \begin{aligned} \textrm{find} \quad & (Y,t) \\ \textrm{s.t.} \quad & Y \succeq I \\ \quad & t \geq 1 \\ \quad & F(Y) \preceq t \cdot Q-I \end{aligned} \tag{2} $$ for every homogenous function $F$, such that $\forall \alpha \in \mathbb R, F(\alpha X) = \alpha F(X)$, and every positive semi-definite matrix $Q$.

First, we define what it means for the problem in $(1)$ to be equivalent to the problem in $(2)$. There are two possible outcomes of the problem in $(2)$: Either a $Y$ exists that satisfies the feasibility constraints, or it doesn't. When a $Y$ exists that satisfies the feasibility constraints in $(2)$, we want to be able to say that there exists an $X$ (not necessarily equal to $Y$) that satisfies the feasibility constraints in $(1)$. Similarly, when there does not exist a $Y$ that satisfies the feasibility constraints in $(2)$, we want to be able to say that there does not exist an $X$ that satisfies the feasibility constraints in $(1)$.

Therefore, the problem in $(1)$ is equivalent to the problem in $(2)$ if the following two statements are true:

- If there exists a $t \in \mathbb R$ and $Y$ such that $Y \succeq I, t \geq 1,$ and $F(Y) \preceq t \cdot Q - I$, then there exists an $X$ such that $X \succ 0$ and $F(X) \prec Q$.

- If there does not exist a $t \in \mathbb R$ and $Y$ such that $Y \succeq I, t \geq 1$ and $F(Y) \preceq t \cdot Q - I$, then there does not exist an $X$ such that $X \succ 0$ and $F(X) \prec Q$.

We first prove statement (1) as follows. Suppose that there exists a $t \in \mathbb R$ and $Y$ such that $Y \succeq I, t \geq 1,$ and $F(Y) \preceq t \cdot Q - I$. Next, let $Y = tX$. Because $Y \succeq I$ and $I \succ 0$, then $Y \succ 0$, such that $X \succ 0$, as desired.

Next, because $F(Y) \preceq t \cdot Q - I$ and $Y = tX$, then $$ \begin{align} F(Y) &\preceq t \cdot Q - I \\ F(tX) &\preceq t \cdot Q - I \\ tF(X) &\preceq t \cdot Q - I \\ F(X) &\preceq Q - \frac{1}{t}I \\ \end{align} $$ Finally, because $\frac{1}{t} > 0$ for every $t \geq 1$, then $Q - \frac{1}{t}I \prec Q$, such that $F(X) \prec Q$, as desired.

Next, we prove statement (2). We do so by proving the contrapositive of statement (2), which is: "If there exists an $X$ such that $X \succ 0$ and $F(X) \prec Q$. then there exists a $t \in \mathbb R$ and $Y$ such that $Y \succeq I, t \geq 1$ and $F(Y) \preceq t \cdot Q - I$".

Suppose that there exists an $X$ such that $X \succ 0$ and $F(X) \prec Q$. First, note that $X \succ 0 \iff \forall t \geq 1, tX \succ 0$. Moreover, for every $t \geq 1$, and for every $\lambda_1 \in (0,t\lambda_\min(X)]$, we have that $tX - \lambda_1 I \succeq 0$, or $tX \succeq \lambda_1 I$, where $\lambda_\min(X)$ is the smallest positive eigenvalue of $X$. Then, choose $t$ such that $$ t \geq \max\left(1,\frac{1}{\lambda_\min(X)},\frac{1}{|\lambda_\max(F(X) - Q)|}\right) \tag{3} $$ where $\lambda_\max(F(X) - Q)$ is the largest negative eigenvalue of $F(X) - Q$. Note that this choice of $t$ given in $(3)$ is guaranteed to be greater than or equal to $1$. Then, with the choice of $t$ given in $(3)$, we have that $t\lambda_\min(X) \geq 1$, such that $\lambda_1 \in (0,t\lambda_\min(X)]$ can always be chosen to be greater than or equal to $1$. Hence, choose any $\lambda_1 \geq 1$ and let $Y = tX$. Because $tX \succeq \lambda_1I$, as shown above, then $Y \succeq \lambda_1 I \succeq I$, as desired.

Similarly, note that $F(X) - Q \prec 0 \iff \forall t \geq 1, t \cdot (F(X) - Q) \prec 0$. For the same choice of $t$ given in $(3)$, and for every $\lambda_2 \in (0,t \cdot |\lambda_\max(F(X) - Q)|]$, we have that $t \cdot (F(X) - Q) + \lambda_2I \preceq 0$, or $t F(X) - t Q \preceq -\lambda_2I$. Additionally, note that $t \cdot |\lambda_\max(F(X) - Q)| \geq 1$, such that $\lambda_2 \in (0,t \cdot |\lambda_\max(F(X) - Q)|]$ can always be chosen to be greater than or equal to $1$. Hence choose any $\lambda_2 \geq 1$, such that $$ \begin{align} t F(X) - t Q &\preceq -\lambda_2I \\ F(tX) &\preceq t Q -\lambda_2I \\ F(Y) &\preceq t Q -\lambda_2I \\ &\preceq t Q - I \\ \end{align} $$ as desired.

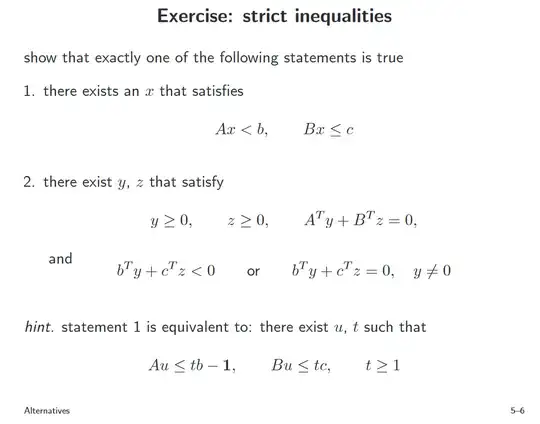

This is a generalization of the following theorem for linear (vector) inequalities: $$ \exists x, Ax < b, Bx \leq c \iff \exists (u,t), Au \leq tb - \mathbf 1, Bu \leq tc, t \geq 1 $$ for every set of matrices $A,B$ and vectors $b,c$. This theorem is part of an example of Farkas' lemma and can be found in slide 6 in "Lecture 5: Alternatives" by Lieven Vandenberghe (available online here and screenshot of the slide below).

- 1,528