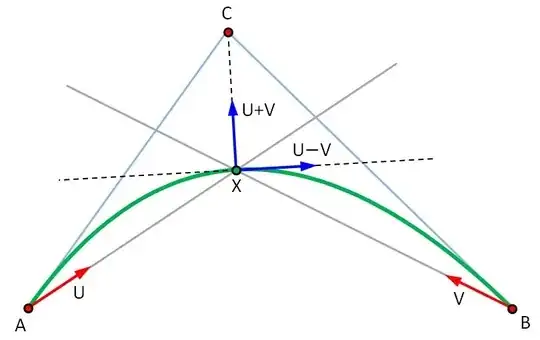

For simplicity of derivation, choose a coordinate system such that $\vec{X}$ is the origin.

The quadratic curve between $\vec{A}$ and $\vec{B}$ has the parametrization:

$$[0,1] \ni s \quad\mapsto\quad \vec{\gamma}(s) = (1-s)^2 \vec{A} + s^2 \vec{B} + 2s(1-s)\vec{C}$$

Since $\vec{X}$ lies on the quadratic curve, for some $t \in [0,1]$,

$\vec{\gamma}(t) = \vec{X} = \vec{0}$. This implies

$$\vec{C} = -\frac12 \left( \lambda^{-1} \vec{A} + \lambda \vec{B} \right)

\quad\text{ where }\quad \lambda = \frac{t}{1-t}.$$

So the problem of locating $\vec{C}$ reduces to the problem of figuring out the parametrization parameter $t$ for $\vec{X}$.

The tangent vector for the quadratic curve at $X$ is given by:

$$\gamma'(t) = \left.\frac{d\vec{\gamma}(s)}{ds}\right|_{s=t} = -2(1-t)\vec{A} + 2t\vec{B} + 2(1-2t)\vec{C} $$

Notice

$$\lambda = \frac{t}{1-t} \implies t = \frac{\lambda}{1+\lambda},\;\;1 - t = \frac{1}{1+\lambda} \;\;\text{ and }\;\; 1 - 2t = \frac{1-\lambda}{1+\lambda}$$

We find

$$ \gamma'(t) = -\frac{2}{1+\lambda}\vec{A} + \frac{2\lambda}{1+\lambda} \vec{B} - \frac{1 - \lambda}{1+\lambda}

\left( \lambda^{-1} \vec{A} + \lambda \vec{B} \right)

= \lambda \vec{B} - \lambda^{-1}\vec{A}

$$

The condition that $\vec{X}$ is the point on $\vec{\gamma}(s)$ closest to $\vec{C}$ can be expressed as:

$$\gamma'(t) \cdot \vec{C} = 0

\quad\iff\quad

\left( \lambda^2 \vec{B} - \vec{A} \right) \cdot \left( \lambda^2 \vec{B} + \vec{A} \right) =

\lambda^4 R_B^2 - R_A^2 = 0

$$

where $R_A = |\vec{A}| $ and $R_B = |\vec{B}|$.

This give us

$$\lambda = \sqrt{R_A/R_B}

\quad\implies\quad\vec{C} = -\frac{\sqrt{R_AR_B}}{2}\left( \frac{\vec{A}}{R_A} + \frac{\vec{B}}{R_B} \right)$$

Update

In the general case when $\vec{X}$ is not the origin, let

$$\vec{A} = (A_x,A_y),\;\;\vec{B} = (B_x,B_y),\;\;\vec{C} = (C_x,C_y),\quad\text{ and }\quad \vec{X} = (X_x,X_y).$$

The distances of $\vec{A}$, $\vec{B}$ from $\vec{X}$ become

$$\begin{cases}

R_A = & \sqrt{(A_x - X_x)^2 + (A_y - X_y)^2}\\

R_B = & \sqrt{(B_x-X_x)^2 + (B_y-X_y)^2},

\end{cases}$$

and the coordinates of $\vec{C}$ turns into:

$$\begin{cases}

C_x = & X_x -

\frac{\sqrt{R_A R_B}}{2}\left(\frac{A_x - X_x}{R_A} + \frac{B_x - X_x}{R_B}\right)\\

\\

C_y = & X_y -

\frac{\sqrt{R_A R_B}}{2}\left(\frac{A_y - X_y}{R_A} + \frac{B_y - X_y}{R_B}\right)

\end{cases}$$

- black curve is what we get, yellow is a desired curve. it looks nice only if you drag in the middle - that's why I was looking for a better solution

– bub

Sep 09 '13 at 23:53

- black curve is what we get, yellow is a desired curve. it looks nice only if you drag in the middle - that's why I was looking for a better solution

– bub

Sep 09 '13 at 23:53