In the book An Introduction to Quantum Field Theory by Peskin and Schroeder, p. 14 in section 2.1, it is stated that, in looking at the asymptotic behavior for $x^{2} \gg t^{2}$ of the integral \begin{equation} \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \mathrm{d}p \; p \, \mathrm{e}^{\phi(p)}, \qquad \phi(p) = i\left( p x - t \sqrt{p^{2} + m^{2}}\right),\tag{1} \end{equation} one can implement the method of stationary phase.

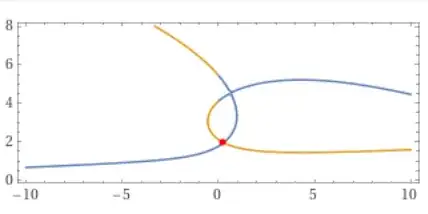

However, the stationary points of $\phi(p)$, $$p_{\pm} = \pm imx/\sqrt{x^{2} - t^{2}},\tag{2}$$ are imaginary, which would seem to indicate to me that the method of stationary phase is not applicable as is. The book then mentions that one can "freely push the contour upward", but exactly how and why is not clear to me.

After looking around, it seems that the asymptotic behavior can be obtained by using the method of the steepest descent. However, I don't understand the following:

How does one chooses a contour in the complex plane such that, through Cauchy's theorem I suppose, relates to the integral above, while at the same time passing through one of the stationary points.

Should one choose only one of the stationary points? If yes, why?

Any help is greatly appreciated.