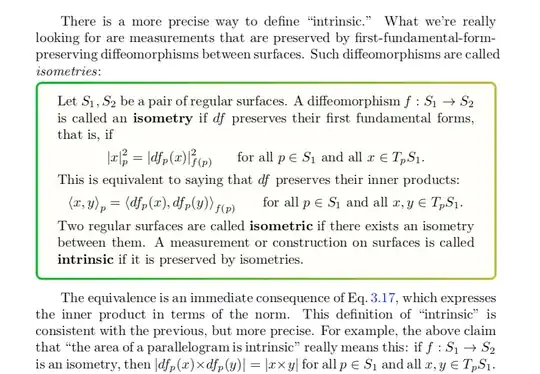

The definitions are consistent in the sense that a measure that is completely described in terms of the first fundamental form is preserved by isometries, since isometries preserve the first fundamental form, so the second definition "contains" the first one.

You might ask yourself what happens with the measurements that are preserved by isometries but are independent of the first fundamental form:

You could say that those measurements depend on the first fundamental form on a "trivial way", but this might be a bit dangerous.

An isometry is in particular a diffeomorphism, so the measurements that it preserves are precisely those that are described by the first fundamental form, or those that are preserved by diffeomorphisms, that is, the topological and differential structures of the space.

So the way I suggest you think about it is the following: an isometry is a map that preserves

The set structure (number of points): it is a bijection

The topology: it is a homeomorphism

The differentiable structure (which functions on the manifold are differentiable): it is a diffeomorphism

The measurements or geometrical properties (the first fundamental form): it is an isometry

Then the first definition is focusing on this last point, and the second contemplates all of them. Notice that each condition is stronger than the previous one and contains it.

This can be generalised to any dimensions by swapping regular surfaces for Riemannian manifolds and first fundamental form for Riemannian metric.

From your last point, the word "deforming" ought to be made precise, but as long as the deformation is a bijection, a homeomorphism or a diffeomorphism (or an isometry, of course), it is contained in the definition of isometry.

Let me know in the comments whether this answers the question :)