Short answer: Your proof is correct and well-written.

Longer answer: Depending on how far you wish to take this question there are varying degrees of complexity to which an answer may exhibit. This all depends on what you allow yourself to assume. Namely, you take for granted that $A$ and $(A \implies B)$ together mean that $B$ is $\operatorname{True}$ (and you do the same for $B$ and $C$). This is, of course, intuitively obvious but you have not mathematically justified it.

This property is referred to as Modus Ponens and you can refer to this as a justification for why you were able to conclude that $B$ holds. However, you may already be thinking that this doesn't answer the question of why the property holds.

If you are familiar with the following implications: $$\operatorname{True} \implies \operatorname{True}$$

$$\operatorname{True} \newcommand{\notimplies}{\;\not\!\!\!\implies} \notimplies \operatorname{False}$$

$$\operatorname{False} \implies \operatorname{True}$$

$$\operatorname{False} \implies \operatorname{False}$$

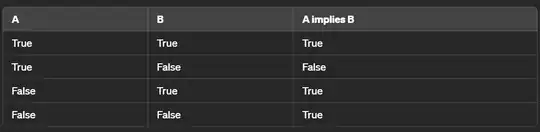

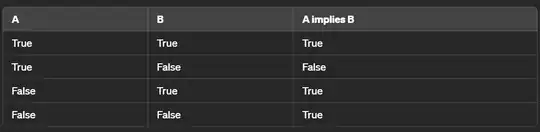

Then you can put these into a Truth Table as follows:

Now you can simply interchange the second and third columns to see that Modus Ponens does indeed hold. However, you may choose to question why this Truth Table holds. Again, this is something that you are likely to find intuitively true, but what is the mathematical justification for this? For that, the answer depends on how you are defining $ \implies$ and the proof can then become significantly more complicated depending on where you choose to start. See the answers to this question for two different characterisations of $\implies$ (note that these are two of the simpler constructions and you can go a lot deeper than this).

And we can continue down an (almost) neverending rabbit hole, going into deeper and deeper levels of formalism. At some point, you have to stop though and consider the purpose of the exercise.

To me, the argument you gave, as I said at the beginning, is completely correct and fine. Although, this is a question where you have the liberty to make it as easy or as complicated as you like.