In logic, the sentence $\boldsymbol{\text‘P}$ implies $\boldsymbol {Q\text’}$ just means that $\boldsymbol P$ being true necessitates that $\boldsymbol Q$ is true.

(In particular, the assertion $\text‘P$ implies $Q\text’$ with $P$ being false allows us to deduce neither that $Q$ is true nor that $Q$ is false. Therefore, regardless of $Q$'s truth value, whenever $\boldsymbol P$ is false, it must be the case that $\boldsymbol P$ implies $\boldsymbol Q.)$

Implication statements, being underpinned by material implication, do not express causation, modality, or counterfactuals.

For example, it is true that 2 is an even number implies that Earth's moon is not made of cheese.

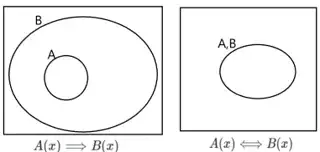

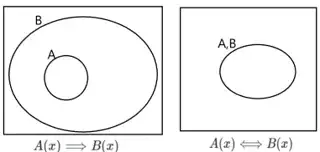

The statement x > 12 implies that x > 10 is not a genuine example of $\text‘P$ implies $Q\text’,$ but an example of the universal implication $\text‘\boldsymbol{\forall x\,(P(x)}$ implies $\boldsymbol{Q(x))}\text’,$ where the condition and consequent are linked by the variable $x,$ every value of which is to satisfy the statement. A visual explanation:

Note that truth is relative to the context. Typically, underpinning implication statements, like the last two, are various definitions (e.g., what ‘a > b’ means), axioms and/or real-world knowledge; these tacit assumptions are part of the aforementioned context, and enable us to legitimately assert implications between statements that may not be ostensibly related.

Other implication statements require none of these contexual assumptions and are true by virtue of their logical form; they are specifically called logical implication. Examples of such strong assertions are Jammy is both kerplung and zingsty implies that Jammy is not neither kerplung nor zingsty and ∀x (x>5 implies that x>5 or x<9), which are true irrespective of what ‘kerplung’, ‘zingsty’, ‘>’ and ‘<’ mean).

Roughly speaking, a logical truth is a sentence that is true regardless of how its non-logical symbols are interpreted. So, logical truths, including logical implications, are context-insensitive.

We can then classify implication into four categories:

- $P$ implies $Q$

- Some complex number is real implies that every positive number is real. (context: mathematical analysis)

- $P$ logically implies $Q$

- It is logically true that $\big(A\to\forall y\,By\big)\,$ implies $\,\exists y\big(A\to By\big).$

- $Px$ universally implies $Qx$

- Every multiple of $6$ is even. (context: mathematical analysis)

- $Px$ logically universally implies $Qx$

- It is logically true that every object that isn't itself satisfies $Qx,$ where $Qx$ is any well-defined propositional function.

The (non-quantified) statement I am holding a pen implies that it is raining outside (whose specific context might tacitly be right now, in Ximending, Taipei) is asserting neither causation nor a timeless truth, and is not predicting that it will rain whenever you hold a pen. It is indeed false in some context(s), since it isn't logically true.

On the other hand statement, this statement is logically true (true in every imaginable context), in other words, a logical validity: I am holding a pen and every empty-handed person is holding no object implies that I am not empty-handed.

Blockquote 5 > 4. This implies: 5 > 3, 5 > 2, and 5 > 1. If any of those statements after the first is useful in a proof, you are allowed to pull that statement out of thin air and use it. That use of implies is pretty confusing when you first start doing proofs, because for the first time the student is free to use what they know of numbers and counting to prove something is true. An original statement created as part of proving a hypothesis true.

– William Parrish Apr 09 '22 at 22:50