The webpage Rounding Up To $\pi$ defines a certain "rounding up" function by an extremely simple procedure:

Beginning with any positive integer $n$, round up to the nearest multiple of $n-1$, then up to the nearest multiple of $n-2$, and so on, up to the nearest multiple of $1$. Let $f(n)$ denote the result.

E.g., using an obvious notation, the sequence starting with $n=10$ is $$ 10 \xrightarrow{9} 18 \xrightarrow{8} 24 \xrightarrow{7} 28 \xrightarrow{6} 30 \xrightarrow{5} 30 \xrightarrow{4} 32 \xrightarrow{3} 33 \xrightarrow{2} 34 \xrightarrow{1} 34 =:f(10). $$

The interesting thing is that, according to the webpage$^\dagger$, $(f(1),f(2),f(3),\dots)$ is the same sequence that results from a certain sieving method, for which Erdős & Jabotinsky (1958) proved that $$ \lim_{n\to\infty}\frac{n^2}{f(n)} = \pi, $$

so one naturally wonders what happens if, instead of rounding up to the nearest multiple, we round up to the second-nearest multiple, or the third-nearest, etc. Thus, let $f_k(n)$ denote the result of the "rounding up" sequence when using the $k^{\mathrm{th}}$-nearest multiple; e.g., using the second-nearest multiple, the sequence beginning with $10$ is $$ 10 \xrightarrow{9} 27 \xrightarrow{8} 40 \xrightarrow{7} 49 \xrightarrow{6} 60 \xrightarrow{5} 65 \xrightarrow{4} 72 \xrightarrow{3} 75 \xrightarrow{2} 78 \xrightarrow{1} 79 =: f_2(10). $$

(These $f_k$ sequences occur in the OEIS under names like "Generalized Tchoukaillon (or Mancala, or Kalahari) solitaire" or related sieving processes, e.g. at the links $f_1$, $f_2$, $f_3$, $f_4$.)

Now let $g_k(n):={n^2/f_k(n)}$ and, assuming all the limits exist, define the sequence $(G_k)_{k=1,2,3,\dots}$ as $$ G_k := \lim_{n\to\infty} g_k(n) = \lim_{n\to\infty}\frac{n^2}{f_k(n)}. $$

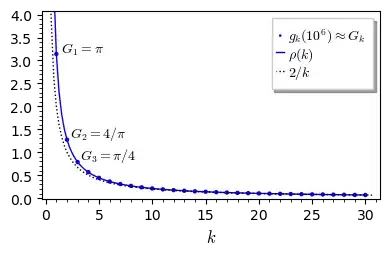

Here's a plot of $(g_k(10^6))_{k=1,\dots,30}$ in which the $g_k$ have apparently converged in at least their first $5$ digits (numerically, it appears that generally the first $d$ digits of $g_k(10^{d+1})$ are those of the limit $G_k$):

We know that $G_1=\pi,$ and in the plot I've indicated my conjectured values for $G_2,G_3$ as well, based on a simple pattern that I found by searching numerically among the $g_k(n)$; specifically, I found that $g_{k+1}(n) \approx \frac{4}{k^2\,g_k(n)}$, with the absolute error bounded by $5/n$, i.e., $$ \left|g_{k+1}(n) - \frac{4}{k^2\,g_k(n)}\right| < \frac{5}{n}, \quad k=1,2,3,\dots $$ and also that $$ \left|g_{k}(n) - a_k\right| < \frac{5}{n}, \quad k=1,2,3,\dots $$ with the $a_k$ defined recursively by $a_1=\pi,\; a_{k+1}=\frac{4}{k^2\,a_k},\; k=1,2,3,\dots$ This strongly suggests the following ...

Conjecture: $$ \boxed{\quad G_1 = \pi, \quad G_{k+1} = \frac{4}{k^2\,G_k}, \quad k=1,2,3,\dots \quad}\tag{1} $$

i.e., $$ (G_k)_{k=1,2,3,\ldots} = \left(\pi,\, \frac{4}{\pi},\, \frac{\pi}{4},\, \left(\frac{2}{3}\right)^2 \frac{4}{\pi},\, \left(\frac{3}{4} \frac{1}{2}\right)^2 {\pi},\, \left(\frac{4}{5} \frac{2}{3}\right)^2 \frac{4}{\pi},\, \left(\frac{5}{6} \frac{3}{4} \frac{1}{2}\right)^2 {\pi},\,\ldots \right). $$

Question: How to prove the recurrence relation in (1)??

NB: From the conjecture (1) it's straightforward to derive the following formulas that hold for all positive integers $k$:

$$G_k=\begin{cases}\left(\prod_{j=1}^{k-1\over 2}{2j-1\over 2j}\right)^2\pi&\text{if $k$ is odd}, \\ \left(\prod_{j=1}^{k-2\over 2}{2j\over 2j+1}\right)^2 {4\over\pi}&\text{if $k$ is even}\end{cases}\\ $$

$$G_k=\left({(k-2)!!\over(k-1)!!}\right)^2\cdot \begin{cases} \pi&\text{if $k$ is odd},\\[3ex] {4\over\pi}&\text{if $k$ is even}\end{cases}\\ $$

$$G_k\sim{2\over k}$$

where the last line is from the known asymptotic behavior of double factorials.

EDIT: As noted in a comment by Ash Malyshev, the conjectured $(G_k)_{k=1,2,3,\dots}$ can also be written compactly as a ratio of squared gamma functions that I'll call $\rho(k)$:

$$G_k = \left({\Gamma\left({k\over 2}\right) \over \Gamma\left({k+1\over 2}\right)}\right)^2=:\rho(k)$$

This can be established either by deriving it from the above formulas, or by showing that $\rho(k)$ satisfies the defining recursion (1). I've updated the above plot to include the continuous function $\rho$ (blue curve) on the real interval $(0, 30]$: The conjecture is that the blue dots ($G_k$) coincide with this curve at every positive integer $k.$

EDIT: Yet another form in which this can be written is the infinite continued fraction $$\begin{align*}G_k= \cfrac{4}{x+\cfrac{1^2}{2x+\cfrac{3^2}{2x+\cfrac{5^2}{2x+\ddots}}}} \end{align*}$$ where $x=2k-1$. This follows from the identity $$x+{1^2\over2x+}\,{3^2\over2x+}\,{5^2\over2x+}\,\cdots=4\left({\Gamma({x+3\over4})\over\Gamma({x+1\over4})}\right)^2,\quad x>0$$ which [Perron, Die Lehre von den Kettenbruchen, Band II, 1957, p.36] attributes to Ramanujan (and to Euler for selected values of $x$).

$^\dagger$ The "rounding up" function $f$ is actually implicit in the proof given by Erdős & Jabotinsky; see this answer by Misha Lavrov for more detail.

For reference, here is the program I used for $f_k(n)$:

# Python

def f(k,n):

y = n

for x in range(n-1,0,-1): # i.e., for x = n-1, n-2, ..., 1

y = ((y-1)//x + k)*x # i.e., y <- k-th multiple of x not less than y

return y

Also, in view of the possible relevance of sieves for proving conjecture (1), here is a program implementing the following algorithm, which I claim generates the $f_k$:

Starting with seq$_1$ = $(1,2,3,\dots)$, let seq$_{i+1}$ be the result of deleting from seq$_i$ the first $k−1$ elements and then deleting every $(i+1)$th element from those remaining. $f_k(n)$ will be the first element of seq$_n.$

def sieve(k, maxel): # generates f_k(1), ..., f_k(n) <= maxel

seq = list(range(1, maxel+1)) # seq_1 = (1,2,3,...,maxel)

keep = seq[:1] # keep the first element of seq_1

i = 1

while seq: # while seq is not empty

del seq[:k-1] # delete the first k-1 elements

del seq[::i+1] # delete remaining elements with index divisible by i+1

keep += seq[:1] # keep the first element of seq_(i+1)

i += 1

return keep