Your functions belong to the following set :

$$\begin{cases}\Phi_1(x)=x, & \Phi_2(x)=1-\tfrac{1}{x},&\Phi_3(x)=\tfrac{1}{1-x},\\

\Phi_4(x)=1-x, & \Phi_5(x)=\tfrac{1}{x},

& \Phi_6(x)=\tfrac{x}{x-1}\end{cases}$$

of 6 functions which is "closed" for composition, and moreover has a group structure for this operation of composition (see remark 1 at the bottom of this answer). A detailed explanation can be found in an old answer of mine here.

Let us take it from the beginning.

Have you noticed that all the operations you are doing deal with so-called homographic functions (sometimes called Möbius functions) having the form

$$\varphi(x)=\frac{ax+b}{cx+d} $$

for certain coefficients $a,b,c,d$. For example,

if $a=1, b=-1, c=1, d=0,$ one gets function $f(x)=1-\frac1x=\frac{x-1}{x} ;$

if $a=0, b=1, c=1, d=0,$ one gets function $g(x)=\frac1x$ ;

if $a=-1, b=1, c=0, d=1,$ one gets (affine) function $h(x)=1-x=\frac{-x+1}{0x+1}$, which can be considered as a homographic function, etc.

The main point is that when two homographic functions $f(x)=\frac{ax+b}{cx+d}$ and $g(x)=\frac{a'x+b'}{c'x+d'}$ are composed in the following way $g \circ f(x)=g(f(x))$, you find back a homographic function.

Proof :

$$g(f(x))=\frac{a'f(x)+b'}{c'f(x)+d'}=\frac{a'\tfrac{ax+b}{cx+d}+b'}{c'\tfrac{ax+b}{cx+d}+d'}=$$

$$=\frac{a'(ax+b)+b'(cx+d)}{c'(ax+b)+d'(cx+d)}=$$

$$=\frac{(a'a+b'c)x+(a'b+b'd)}{(c'a+d'c)x+(c'd+d'd)}$$

One often prefers to reason on square arrays called matrices (maybe you haven't seen them yet) under the form :

$$\underbrace{\pmatrix{a'&b'\\c'&d'}}_{\text{coeff. of } g} \underbrace{\pmatrix{a&b\\c&d}}_{\text{coeff. of } f} = \underbrace{\pmatrix{(a'a+b'c)&(a'b+b'd)\\(c'a+d'c)&(c'd+d'd)}}_{\text{coeff. of } g \circ f}$$

For example, your calculation $f(1/x)=-x+1$ corresponds to the following matrix product :

$$\underbrace{\pmatrix{1&-1\\1&0}}_{\text{coeff. of } f}\underbrace{\pmatrix{0&1\\ 1&0}}_{\text{coeff. of } 1/x}=\underbrace{\pmatrix{\color{red}{-1}&\color{red}{1}\\\color{red}{0}&\color{red}{1}}}_{\text{coeff. of} -x+1} $$

i.e., with notations above :

$$\Phi_2 \circ \Phi_5 = \Phi_4 $$

The set of homographic functions is infinite, whereas the group you use is finite (as said at the beginning of this answer).

Remarks :

- If you have already met the notion of "group" in mathematics, here are some precision about the so-called "anharmonic group" of 6 functions ; its "Cayley table" for the composition operation is as follows :

$$\begin{array}{c|cccccc}

\circ & \Phi_1 & \Phi_2 & \Phi_3 & \Phi_4 & \Phi_5 & \Phi_6 \\

\hline

\Phi_1 & \Phi_1 & \Phi_2 & \Phi_3 & \Phi_4 & \Phi_5 & \Phi_6\\

\Phi_2 & \Phi_2 & \Phi_3 & \Phi_1 & \Phi_6 & \Phi_4 & \Phi_5\\

\Phi_3 & \Phi_3 & \Phi_1 & \Phi_2 & \Phi_5 & \Phi_6 & \Phi_4\\

\Phi_4 & \Phi_4 & \Phi_5 & \Phi_6 & \Phi_1 & \Phi_2 & \Phi_3\\

\Phi_5 & \Phi_5 & \Phi_6 & \Phi_4 & \Phi_3 & \Phi_1 & \Phi_2\\

\Phi_6 & \Phi_6 & \Phi_4 & \Phi_5 & \Phi_2 & \Phi_3 & \Phi_1 \end{array}$$

Do you retrieve relationship $\Phi_2 \circ \Phi_5 = \Phi_4 $ ? (which is different from $\Phi_5 \circ \Phi_2 = \Phi_6$ : the group isn't commutative). Please note also that function $\Phi_1$ defined by $\Phi_1(x)=x$ is neutral for function's composition which is quite logical...

You can notice in particular that the three first functions constitute a stable subset (in fact a particular subgroup).

The main group is isomorphic to $S_3$, the group of the $3!=6$ permutations on 3 elements ; the subgroup $\{\Phi_1,\Phi_2,\Phi_3\}$, which is the subgroup of matrices having $\det=1$, is isomorphic to the so-called alternating group $A_3$.

A homographic function is defined by its four coefficients up to a multiplicative factor : $(ka,kb,kc,kd)$ gives the same function as $(a,b,c,d)$ due to simplication by $k$. This property is called, for reasons that we will not give here, a "projective property".

Now, in case you have already studied complex numbers, here is a completely different view on functions $\Phi_k$ when they are considered no longer as functions $\mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}$ but as functions $\mathbb{C} \to \mathbb{C}$.

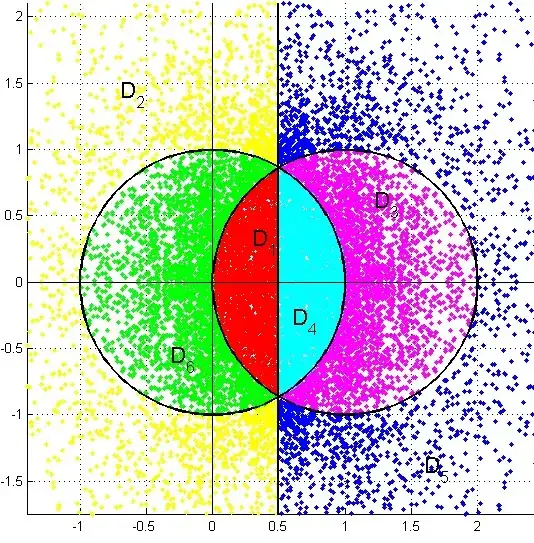

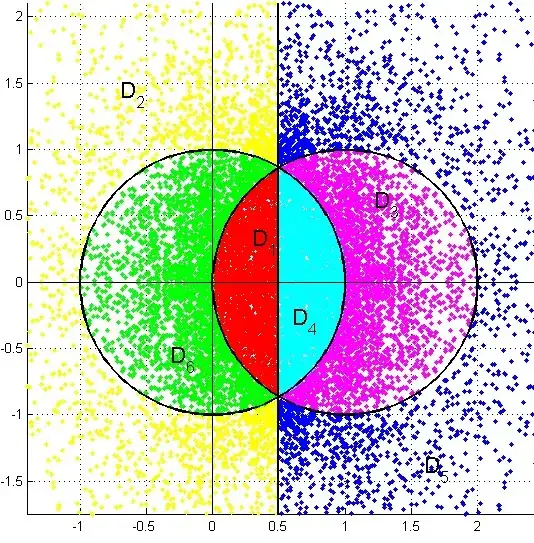

Let us start from a value of $z$ belonging to the so-called fundamental domain $D_1$ in red. If we apply to it function $\Phi_2$ defined by $\Phi_2(z)=1-\tfrac{1}{z}$, one will obtain a point in the yellow region. If, instead, we apply to it function $\Phi_4(z)=1-z$, you will obtain a point in region $D_4$ etc. In this way, all the plane is covered.

(The figure has been created by taking $5000$ random points in the red area, then computing their images by the different $\Phi_k$.)