Ultimately, I don't think there's a much better answer to "where does it come from?" besides throwing up our hands and saying, "magic!" The technically correct answer is that we can create an orthonormal basis for $\mathbb{O}$ which is closed up to multiplication (up to sign) because of iterative vector rejection and normalization combined with the fact the Cayley-Dickson construction functions as identities in a generic real normed division algebra because of tricky polarization and inner product manipulations. I will give some of the history and logic behind where these tensors originate, and (IMO) more memorable mnemonics for octonion multiplication (namely, alternativity + "special anti-associativity" for one convention, or triangles in a heptagon + shifting indices mod $7$ in a different convention).

The quaternions battled with vectors and geometric algebra (AKA Clifford algebra, slightly more often than not with opposite sign conventions) for primacy in curriculum and physics usage for modeling rotational mechanics and electromagnetism (Maxwell's equations). While quaternions had their day due to Hamilton's evangelism, as we all know they died out in favor of vectors (which separated the real and imaginary parts of quaternion multiplication into dot product and cross product), now much more standard material in undergraduate math and physics. Arguably, quaternions and then octonions have made a comeback, quaternions with rotational mechanics in 3D (and, mathematically, in 4D), and octonions in relation to spin and exceptional objects (even in the discrete world!).

After the Frobenius Theorem classified real associative division algebras ($\mathbb{R},\mathbb{C},\mathbb{H}$), Hurwitz Theorem classified real normed division algebras ($\mathbb{R},\mathbb{C},\mathbb{H},\mathbb{O}$ are the positive-definite cases). The general, abstract setting is, well, you start with a real normed division algebra and begin making inferences. First off, a norm gives you an inner product after "polarizing." Left and right multiplication of elements by unit-magnitude elements are isometries. Define elements orthogonal to real numbers as imaginary and then all elements have real and imaginary parts. Unit imaginary elements are the square roots of negative one. Elements commute iff their imaginary parts are parallel and anticommute iff they are orthogonal and imaginary. You can prove these things and more in different orders with varying degrees of naturality/difficulty, though a running theme is variations on the "polarization" trick.

Given a real normed division algebra, you can build up subalgebras by picking one element at a time. First, it comes equipped with $\mathbb{R}$ as a subalgebra, then you can pick any element $a$ outside of it to generate a complex subalgebra $\mathbb{R}[a]\cong\mathbb{C}$ (the normalized imaginary part of $a$ corresponding to $\mathbf{i}$), then pick any element $b$ outside of $\mathbb{R}[a]$ to generate a quaternionic subalgebra $\mathbb{R}[a,b]\cong\mathbb{H}$, this time with $\mathbf{j}$ corresponding to the normalized imaginary part of $b$'s vector rejection away from $\mathbb{R}[a]$ (considered as a 2D plane). If $B$ is any proper subalgebra, we can pick an element outside of $B$, reject it away from $B$ (i.e. chop off the parallel component WRT $B$), and normalize the imaginary part to get $\ell$, then consider the "doubled" subalgebra $B\oplus B\ell$. Some tedious algebra shows it obeys the Cayley-Dickson construction rules, so in effect all real normed division algebras emanate from applying this construction to $\mathbb{R}$. But not conversely: applying it to $\mathbb{O}$ yields the sedenions $\mathbb{S}$ which is not division.

The construction process puts in our head, for octonions, the idea of special triples like $(\mathbf{i},\mathbf{j},\ell)$. (I have seen a niche term for these triples, but don't recall what it is. Might have literally just been "special triples.") These are triples $(\mathbf{u},\mathbf{v},\mathbf{z})$ of unit imaginary octonions for which $\{1,\mathbf{u},\mathbf{v},\mathbf{uv},\mathbf{z},\mathbf{uz},\mathbf{vz},(\mathbf{uv})\mathbf{z}\}$ forms an orthonormal basis for $\mathbb{O}$; or equivalently has the same multiplication table as the corresponding set for $\{\mathbf{i},\mathbf{j},\ell\}$; or equivalently generates a loop isomorphic to that generated by $\mathbf{i},\mathbf{j},\ell$; or equivalently $\mathbf{u},\mathbf{v}$ are orthogonal and $\mathbf{u},\mathbf{v},\mathbf{uv}$ are all orthogonal to $\mathbf{z}$. These are useful for understanding the structure of the symmetry group $\mathrm{Aut}(\mathbb{O})\cong G_2$ which acts not just transitively on unit imaginary octonions (i.e. $S^6$) but acts regularly on special triples.

Since every two elements generate at most a quaternionic subalgebra, which is associative, the octonions are still alternative, which says any product involving just two elements (or also their conjugates and inverses) can be parenthesized however without affecting the result, e.g. $a(ab)=(aa)b$ and $a(ba)=(ab)a$. (When considering possible four-term three-variable identities, we can get the Moufang identities.) Just as elements anticommute iff they are imaginary and orthogonal, we can go further and prove unit octonions $u,v,z$ (not assumed to be imaginary!) anti-associate, i.e. $(uv)z=-u(vz)$, iff $(u,v,z)$ is a special triple.

The aforementioned orthonormal basis for $\mathbb{O}$ generated by a special triple has a multiplication table which can be generated simply using the rules of alternativity and the special anti-associativity. Pretty much any kind of calculation or involved proof I do involving octonions uses alternativity and special anti-associativity.

The orthonormal basis has $2^3=8$ elements corresponding to binary choices of whether or not to include each entry of the special triple in a product, e.g. $(1,1,1)$ could correspond to $(\mathbf{uv})\mathbf{z}$. This allows us to view the Fano plane $\mathbb{F}_2\mathbb{P}^2$ as underlying the imaginary "axes" of the octonions. By viewing vectors in $\mathbb{F}_2^3$ as binary, we can label basis elements $e_0$-$e_7$ (with $e_0=1$) and then $e_1e_2=e_3$, as in the convention you cite. This allows us to calculate the product of basis elements using a Fano plane mnenonic: ignoring sign, the result is the third element in the projective line spanned by two elements.

In your antisymmetric tensor $\varepsilon_{ij}^k$, the symbol is $0$ except when $k$ corresponds to the index you get when multiplying $e_i$ and $e_j$, so the only mystery as to why $\varepsilon_{ij}^ke_k$ is just one basis element is why the basis elements are closed under multiplication (up to sign) to begin with. And the reason that is, recall, is because of the Cayley-Dickson doubling phenomenon which is possible because of iterative vector rejection and normalization to a "special" state. That the rules of the Cayley-Dickson are generic identities in arbitrary real normed division algebras IIRC follows from tricky polarizations and inner product manipulations.

Polarization is the kind of thing you see in versions of the so-called "polarization identity" in vector algebra, it means turning a quadratic form into a bilinear form (in our case, the norm yields an inner product). More generally, polarization turns a homogeneous polynomial into a multilinear form, and the mutually inverse process is called restitution. Besides cancelling left/right multiplication, the most basic feature of inner products for proving identities is nondegeneracy: if $\langle a,x\rangle=\langle b,x\rangle$ for all $x$, then $a=b$. The trickiest recurring manifestation of this I recall was a polarization which turned $\langle ab,cd\rangle$ into a weighted average of other permutations of the same expression (I don't have my personal octonion notes on hand).

Personally, I find the Fano plane mnemonic hard to remember because I don't remember the directions involved in the seven projective subspaces. I have to recreate the directions using the alternativity + special anti-associativity rules. However, symmetry can give us a different convention for multiplication which is easier to remember. The automorphisms of $\mathbb{O}$ arising as permutations of a special orthonormal basis (IOW the symmetries of its multiplication table) is none other than the symmetry gruop $\mathrm{PGL}_3\mathbb{F}_2$ of the Fano plane. There is a so-called exceptional isomorphism $\mathrm{PGL}_3\mathbb{F}_2\cong\mathrm{PSL}_2\mathbb{F}_7$ which allows us to instead think of the axes of $\mathbb{O}$ as the projective line over $\mathbb{F}_7$ (with the real axis corresponding to $\infty$).

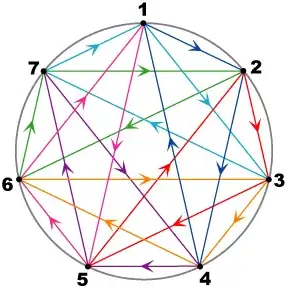

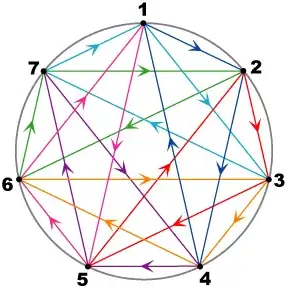

The 3rd and 4th sections of my answer here explain how to do this in more detail. In conclusion, we can start with $124$ and apply shifts mod $7$ to get $7$ different oriented triangles in a regular heptagon. Each such triangle has the same mnemonic as the $\mathbf{ijk}$ cycle for quaternions. It is very easy to draw circles with seven points labelled $1$-$7$ and then figure out the product of any two basis elements using this mnemonic:

It may look complicated (and beautiful!) with all the triangles drawn at once, but really just a blank circle with mental math is how I do most of my octonion calculations in a specific basis. The circle labels and triangle orientations should all turn in the same direction (in this case, clockwise). Observe any two elements differ by $1$, $2$, or $3$ units along the direction, which makes it always possible to envision any two labels in a triangle identical to (and shifted from) the $124$ triangle.

Note these triangles correspond to special triples of basis elements. Whatever convention you use, these triples of indices (ignoring order and signs) form the Steiner system $S(2,3,7)$, i.e. a collection of triples for which every pair is in a unique triple (hence defining a binary operation, yielding the third element of any triple containing two given elements - corresponding to octonion multiplication). This is just a taste of how the octonions and their weird symmetry are related to all sorts of exceptional structures, including the Golay code, Leech lattice, and Jacques-Tits magic square.