It seems to me that most high school students are comfortable with the intuitive notion of a limit ("as $x$ gets arbitrarily close to $c$, $f(x)$ gets arbitrarily close to $L$") and gain little insight from learning the $\varepsilon$-$\delta$ definition. Is the added rigor of the $\varepsilon$-$\delta$ definition worth teaching at the high school level?

11 Answers

I strongly disagree with Arkemis' answer - we should not design the high school math curriculum to cater to the tiny minority of students who go on to become pure math majors, who are the only ones who would really benefit from such material. I'm not convinced that calculus should be taught in high school at all (or if it is, in the form that it usually appears in North American high schools), much more useful would be time spent say, critically analyzing statistical claims made by politicians and journalists.

I don't buy the argument that "definition pushing" somehow improves rigourous thinking in students either. One can demand just as much rigour and clarity of thought from an analysis of Shakespeare than from a $\epsilon - \delta$ proof - the solution is to demand higher standards from the rest of the curriculum, not introduce what amounts to trivia for 99.9% of the students.

By the way, I am speaking a pure mathematician doing academic research for a living.

- 237

-

2I think this is better suited as a (admittedly long) comment to @Arkamis, and not as an answer to the OP's question. – Dan Rust Aug 01 '13 at 10:38

-

11The counter-argument, of course, is that an $\epsilon-\delta$ argument is clearly either right or wrong, whereas scholars have been re-interpreting Shakespeare for close onto 500 years, and so any argument, using sufficiently complicated vocabulary, can be crow-barred into being considered legitimate. Mathematics is not so. Words have different definitions, histories have different interpretations, but mathematical definitions are concrete. – Emily Aug 01 '13 at 19:16

-

While the answer ("No, we shouldn't teach $\epsilon$-$\delta$ to high school students") is defensible, I see a lot of unjustified assumptions in this argument: 1) It is not clear that one needs to be a pure math major to benefit from $\epsilon$-$\delta$. E.g. at UChicago this is covered in all calculus classes whatsoever, which together are taken by the vast majority of undergraduate students. (I also hear a bit of "Should we cater to the tiny minority of students who are extraordinarily talented and interested? What about the students who couldn't care less -- how are we serving them?") – Pete L. Clark Aug 04 '13 at 11:13

-

4

- "[M]uch more useful time...analyzing statistical claims". This creates a false dichotomy: in 99.9% of high schools in the US, calculus is an elective taken only by interested students. The proposed course on analyzing statistical claims would be valuable for everyone. Why can't some students take both? 3) Again, $\epsilon$-$\delta$ vs. Shakespeare is a false dichotomy, this time flagrantly so. Both are valuable for many students, in very different ways. And again, Shakespeare is part of the required curriculum in many schools and districts; not so, calculus.

– Pete L. Clark Aug 04 '13 at 11:15 -

2

- "By the way, I am speaking a pure mathematician doing academic research for a living." If so, then the fact that you are not willing to leave this answer under your own name is not a ringing endorsement. Rather, you seem to have created an account entirely to leave this answer. Why??

– Pete L. Clark Aug 04 '13 at 11:18 -

(By the way, I didn't much like Arkamis's counter-argument either. I agree with anon's "just as much" if we interpret this as "neither more nor less rigorous in the partial ordering of subjects by rigor and clarity of thought". Shakespeare and mathematics are very different wonderful things. They are not in competition in the curriculum; it seems distracting and even a little silly to try to argue for one over the other here.) – Pete L. Clark Aug 04 '13 at 11:27

-

A "pure mathematician" who evidently doesn't understand the general import of mathematical maturity? Of course not everybody can achieve mathematical maturity, especially in high school. However, as it is effectively "knowing how to think", it is important for any real discipline, not just pure math. To say that people analyzing Shakespeare are on the same intellectual level as somebody with mathematicaly maturity is pathetically naive. – Jonathan Aug 04 '13 at 14:19

-

Here is a personal story, and hopefully it will shine some light on some of the trends in recent math education.

I went to a small (US-based) high school that was primarily an agricultural high school. The year I took calculus, it was with a teacher in his last year before retirement. We learned $\epsilon-\delta$ definitions of limits and derivatives before we learned the "exponent rule". However, we didn't really learn proof technique, nor did we learn the importance of definitions nor the preciseness of mathematical language. In fact, we were all quite glad to be done with the formalism by the time we learned that $(x^n)' = nx^{n-1}$. This was in the late 90s.

I then went to a highly-revered engineering school. Calculus classes, and indeed, introductory engineering classes, were all designed around Maple. While we had to learn Calculus, we primarily had to learn it using Maple. As a result, our homework and exams focused on how to apply techniques such as integration by parts in Maple. We had "gateway examinations" on computer that required us to answer questions in Maple-based syntax.

I left my undergraduate program shortly before finishing, due to medical reasons. When I returned 4 years later and changed my major to Mathematics, I had to take real analysis. When we got to the formal definitions of derivatives and limits, the professor asked how many of us knew $\epsilon-\delta$ proofs. I was the only one.

He then asked how many of us went through a Maple-based Calculus education. Again, I was the only one.

In a span of no more than eight years, a prominent Top Tier US university completely overhauled its calculus education not once, but twice.

In both cases, the introductory level material left students woefully underprepared for doing any sort of rigorous math. The introduction of a required "Intro to Proofs" class did very little to skew the comprehension curve in the class.

Truth be told, it was only after quite a long while of self-education that I began to understand analysis, algebra, and mathematics.

Indeed, some may argue that undergraduate real analysis is just definition pushing. But my classmates couldn't even push definitions! We were hopelessly lost!

So, given that high-school students in Calculus are advanced at math, should we teach $\epsilon-\delta$ proofs? In my opinion, yes. But also, in my opinion, it should be done to teach what "proving" something means.

There is nothing wrong with "definition pushing" mathematics, especially at an early level. At the same time, we must still prepare the non-mathematician students for their careers in engineering, finance, or the sciences.

High school is supposed to prepare us for college. The best thing we can do for a college-bound high school student is to teach them how to think. Rigorous thinking applies to many fields.

So if you can teach $\epsilon-\delta$ rigorously, but without losing sight of its imperative, then do so.

Otherwise, find a different way. My educational experience set my mathematical understanding back 10 years, and I "learned" multiple ways. It took me 10 years to figure out what could have been taught to me in a single, well-structured calculus class.

So, to answer your question, yes. The rigor is worth it. But it's only worth it if you can do it right.

- 36,334

-

I share much of the same sentiments, but I am more towards the gray between this and anon's answer. While I do think presenting the definitions are important, and I see many students woefully prepared for forming rigorous arguments, I do not think it should start in a high school calculus course, but rather in some proofing course that lands between calculus and real analysis. Calculus is very intuitive and applicable, and I'd rather not have students worrying over formality at the cost of that. – Simply Beautiful Art Feb 02 '20 at 05:57

Let me try again with a less personal answer.

There are a lot of different high school calculus courses at a lot of different levels. To be honest, a really satisfactory answer to this question would necessitate inquiring into the reasons why so many American high school students take calculus nowadays, and especially, take calculus instead of the more in-depth study of pre-calculus mathematics that used to be considered suitable for even very strong high school students up through their senior year. I think we would find that some of the motives are less than pure.

Instead let me stick with the model of the two kinds of AP Calculus. There is one, called "AB Calculus" and another called "BC Calculus". The letters are weird but the way I understand it is that in the former you spend a year of high school doing what amounts to a semester of college level calculus, whereas in the latter you spend a year of high school doing two semesters of college level calculus. (I know that in some schools students take AB in their junior year and BC in their senior year. I disapprove of this, in part because I cringe to imagine the short-changing of precalculus mathematics that is involved here.) A lot of students who take AB calculus (or, especially, something even less ambitious) end up taking a first semester of university calculus anyway.

Thus I think a reasonable model for AB-type calculus courses is that it is a gentle first introduction to calculus, with the idea that students who are more interested will revisit similar material again in more depth. If you want a gentle first introduction, then you should probably not require the students to do $\epsilon$-$\delta$ proofs.

Let's consider the first introduction aspect more carefully. If you open up a typical freshman calculus text, there will be three sections on limits. The first will be an intuitive introduction, the second will give you tools for computing them, and the third will mention $\epsilon$-$\delta$. I don't entirely agree with this ordering, but I do agree with the idea that you spend a lot of time with limits at various levels of sophistication, and $\epsilon$-$\delta$ is not the first thing you do with them.

But now let me say more about what you can do with limits. First of all, in a first introduction to calculus the primary emphasis should be on the derivative, not on the limit concept. Traditionally freshman calculus books didn't do this so well (they want to maintain the illusion of logical completeness, I guess because if your text looks superficially more logically complete than Professor Y's, then some instructors will complain about Professor Y's text and maybe people will choose yours instead), following a Chapter 1: precalculus, Chapter 2: limits, Chapter 3: derivatives approach. More recently calculus texts seem to have clued in to the fact that it is possible to compute many derivatives without explicitly addressing the limit concept at all. In one view, this is what Newton and Leibniz did. Or rather, they had some words about the limit concepts but those words fell so far short of a logically complete presentation that most of their contemporaries and successors just ignored them and tried to learn the calculations (at least, at first). So for instance, I would like to compute the slope of the tangent line to $y = x^2$ at $x = c$. My idea is as follows: the slope of the secant line between $c$ and $c+h$ is

$\frac{f(c+h)-f(c)}{h} = \frac{(c+h)^2-c^2}{h}$,

and I want to evaluate this at $h = 0$. Well of course if I just plug in $h = 0$ directly I get $\frac{0}{0}$, which doesn't tell me the answer. So I do some algebra first, simplifying to

$\frac{c^2+2ch+h^2-c^2}{h} = 2c+h$.

Now I can sensibly plug in $h = 0$, getting $2c$. If I want to justify this by looking at the graph of $2c+h$ as a function of $h \neq 0$, no problem: the value that I'm interested in is the hole in this graph, so I plug the hole with the value at the point.

This procedure will of course work for all polynomial and rational functions, which is a great place to start: it gives us plenty to work with (We can solve lots of optimization problems using the observation that at a minimum or maximum the slope of the tangent line had better be horizontal, for instance).

Eventually -- but already I could imagine high school calculus courses ending before getting to this -- you'll want to look at an example where the derivative computation is not purely algebraic. E.g. you'll try to differentiate the sine function at zero and get $\frac{\sin h}{h}$. At this point the honest thing to do is graph the function for nonzero values. You'll certainly decide that you want the answer to be $1$ but then you have the task of explaining what is going on. To my mind the next simplest thing to do is to talk about a class of functions whose graphs are "nice curves" and for a nice curve if you simply remove one point from the domain you can see from the nearby values what the value at that point was: it was the unique value which plugs the hole to make a continuous curve. Here I am alluding to the definition of limit in terms of continuity, which I am surprised not to see in freshman calculus texts, since the idea of function being a "nice curve" near a point is much less confusing than the (approach the point)/(what happens at the point is irrelevant!) koan that fries the brains of so many calculus students.

The next step is to realize that "nice unbroken curve" is not helpful enough for calculations. One way to proceed is to (i) assume that the familiar elementary functions are continuous at every point of their domain and (ii) write down "axioms" for combining continuous functions to get continuous functions: namely, $+,-,\cdot,/$ and $\circ$. While we're at it we may want to assume a few basic results that have been experimentally observed, e.g. that defining $\frac{\sin h}{h}$ to be $1$ at $h = 0$ gives a continuous curve. One can then show that $(\sin x)' = \cos x$ using the basic trig identities and check this at various points to see that it works out.

Maybe one is happy with this for a while and wants to move on to integration (Newton and Leibniz did). Or again, maybe the course ends at this point. Or maybe we eventually give a description of continuity in terms of the variation in $y$ always being controllable by making the variation in $x$ sufficiently small: i.e. we discuss some form of the $\epsilon$-$\delta$ definition of continuity. If this is done then one should certainly explain why $f,g$ continuous implies $f+g$ continuous: it's just that the sum of two quantities which can be made arbitrarily small can again be made arbitrarily small. Continuity of the composite function has a similarly clear moral. Doing things like products and quotients is more about algebra tricks than fundamental ideas, so maybe that gets done and maybe it doesn't.

In summary: eventually one should discuss some form of the $\epsilon$-$\delta$ definition of continuity: I wouldn't want to have an entire semester of university freshman calculus without saying something meaningful about the definition of continuity. But almost no student nowadays will be finished with calculus in high school unless they decide that they hate it and don't want to have anything further to do with it. So I think that a more leisurely development of the ideas which allows students to get a sense of how calculus works and is useful even in the simplest nontrivial examples would probably be more appropriate for most AB-type calculus courses. Even in a BC-calculus course I would probably present some $\epsilon$-$\delta$ material in the lectures but spend little or no time asking students to make these types of arguments...unless they are exceptionally strong, well-prepared and interested, or unless they really want to.

- 100,402

-

2While I sympathize with most of your response, I just can't see non-gifted high school students being able to understand epsilon-delta arguments.Worse,since such students are in all likelihood to be mostly honors physical and social science majors expecting to learn techniques they can actual use in those fields, a formal limit approach might alienate them and make most of them become law students. And God knows,we've got too many of them to begin with......lol (The last part was a joke,but you get the idea.) – Mathemagician1234 Jan 25 '15 at 04:57

I'm from Italy, and I was born in 1974. I learned Calculus in a Liceo scientifico, a high school that should prepare to pursue scientific studies at the university. It was 1993, and much has changed in recent years. My professor used to teach the rigorous $\varepsilon$ & $\delta$ approach essentially from the beginning. That's why, as an assistant professor, I am rather skeptic about those US textbooks that introduce limits like they were speaking in a TV show. I am aware that, in Europe, we were strongly influenced by the french school of Bourbaki, and many colleagues now teach as in the US. However, I must also remark that my students at the university know less mathematics that we knew twenty years ago. And they think mathematics is something you can do by hands, without really understanding the definitions. They can compute limits, but they can't define the concept of limits. And, what is worse, they do not want to learn the rigorous definition. In my humble opinion, mathematics should be taught (and thus learned) correctly as soon as possible. If you can't really understand the basic definitions of Calculus when you are 18, then you should seriously think about a career in the humanities.

- 35,786

Using the $\varepsilon$-$\delta$ definition of limit to prove that $\displaystyle \lim_{x \to 3} \dfrac{1}{x+4} = \dfrac 17$ is (to most non-math geeks) tedious and misses the point. The point is that, if $\displaystyle \lim_{x \to x_0} f(x) = L \ne 0$, then $\displaystyle \lim_{x \to x_0} \dfrac{1}{f(x)} = \dfrac 1L$.

Using the $\varepsilon$-$\delta$ definition of limit, you can prove that theorem and many more of that ilk. We are passing up the chance to show these student that, with the help of formal definitions and logic, we can avoid a lot of tedious work.

- 27,619

I strongly agree with Anon' comment that the high school math curriculum should not be designed to cater to the tiny minority of students who go on to become pure math majors, who are the only ones who would really benefit from such material.

It may be useful to broaden the scope of the discussion somewhat, by comparing the effectiveness of epsilon, delta teaching with an alternative approach using infinitesimals. Such an approach is adopted in Keisler's textbook Elementary Calculus.

Teaching experience over several years with hundreds of students indicates that the approach using infinitesimals is more intuitive and therefore more accessible to students, while at the same time fully rigorous.

- 47,573

-

Yeah, why don't we teach infinitesimals in beg. calculus, now that we have non-standard analysis? – MathTeacher Dec 22 '14 at 09:04

-

1

-

@MathTeacher, you could consult this post: http://math.stackexchange.com/questions/1057355/which-universities-teach-true-infinitesimal-calculus – Mikhail Katz Dec 22 '14 at 11:08

There is an assumption that the $\epsilon$-$\delta$ method of teaching limits and continuity is the most "rigorous". It is not the most intuitive. I prefer an emphasis on the domains of real functions, such as $(x^2-1)/ (x-1)$, which is defined on all reals except $1$. So it has an extension to all reals giving the function $x+1$, which is continuous. One also needs examples of non continuous functions, such as $f(x)= x$ for $x \geqslant 1$, $f(x)= -1$ for $x<1$. You can define a neighbourhood of a point $x \in \mathbb R$ to be any set of reals containing an open interval containing $x$, and use the neigbourhood definition of continuity, illustrated by pictures. The $\epsilon$-$\delta$ method is then put in its place as a calculational tool, in which the $\epsilon$, $\delta$ are a sometimes convenient measure of the sizes of particular neighbourhoods, rather than a geometric aspect.

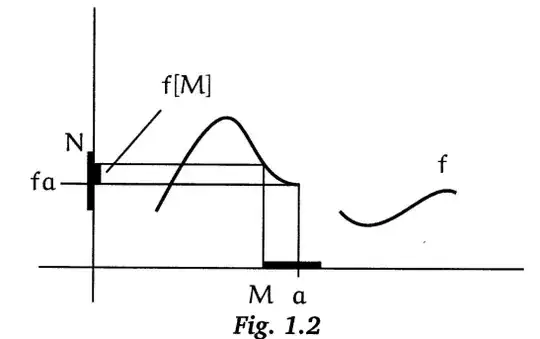

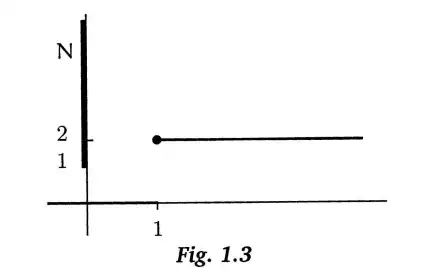

Here is a figure for the definition of continuity

and another for an example of a non continuous function

both taken from my book Topology and Groupoids. Actually the second one illustrates $f^{-1}(N) $ is not a neigbourhood of $1$. (All this was developed in the 1970s at Hull University for first year students and published in a book "A preliminary course in analysis" by R.M.F. Moss and G. Roberts (available from amazon). The students, a mixed bunch, seemed quite happy with this approach.)

The question asked about what is appropriate for high school. I don't claim any experience in this, but I do believe in the use of pictures!

In this approach one develops rules for constructing continuous functions, and this is relevant to modern approaches in which one emphasises the category of topological spaces and continuous functions, rather than just the notion of a topological space.

Another example for all this is to compare the outputs of a radio when you change the volume knob or the tuning knob. One wants the first change to be continuous, while the second to be approximately non-continuous, so that you get sharp tuning.

- 4,000

- 15,909

-

-

2We can always count on Dr.Brown to give a strikingly insightful and surprisingly original comment on an educational dilemma. I'd never heard of this book before now-but rest assured,I'm going to find an old copy now! – Mathemagician1234 Jan 30 '15 at 04:23

I believe that one important aspect of math teaching is linking the formal and the intuitive. Thus, epsilon-delta or epsilon-M proofs should be taught only if it is somehow linked to students' intuitive idea of a limit. I think this is possible by: motivating the definition, and perhaps playing a "game" with students, where you give them a function, say f(x)=1/x, and a specific value, say x=3, and ask them something like "how if x gets big enough, will 1/x be less than 1/3 and say less than 1/3? How big does x have to be for this to be the case?". I think it would have to be done carefully so that students don't think of proofs as somehow separate from their mathematical intuitions.

Professor Roh at ASU does some neat stuff on this that I would suggest checking out.

- 1,639

As I self-teaching student, I believe that the epsilon-delta definition is very useful. The intuitive definition worked great for me, but the rigor behind the epsilon-delta definition is vital. I may be a bit biased as I am planning to pursue a math-related profession in the future, but still think all students should know the definition. Not being able to use the epsilon-delta definition is like understanding the process behind addition, but not really being able to do the procedure (I have a younger sibling hence the analogy). Yes, the epsilon-delta definition took me around a week to learn how to apply and use, but it was worth it in the end. Also, you can PROVE limits with epsilon-delta.

- 11

In my opinion, you should not teach proofs using $\epsilon$ and $\delta$, but you should definitely give the definition of continuity and limits.

Of course, it is very important to explain in english the intuition behind the definition, and I don't think most students need the actual rigorous definition. But I don't think it can hurt anyone to write it down at least once properly in the course. When I was in high school, I remember being frustrated because I wasn't given rigorous definition to match all the "intuitive approach".

Then giving theorems (without proof) that polynomials are continuous, or that a sum of limits is the limit of the sums, at least hold a meaning for the interested student. And for the average/not particularly interested in mathematics students, it's just one line of definition that won't be in the test.

- 9,487

Boy, this is one for the ages so I guess I will take my stab at it. Let's all first agree that the beginnings of rigor come in basic calculus proofs of say the mean value theorem which in my personal opinion should be held off for either high school students who have selected a major already (this is the case in my parents country Iran). But more simple ones such as showing $f(x)=\vert x \vert$ is continuous on $[0,\infty)$ could be taught to say an honors or AP calculus one student. It's all based on the willingness the student has to learn the subject matter. I have been able to show a second grader how to find GCF and LCM but I know high school seniors who can't do $5-24$ in their heads. So it's all based on the "mathematical maturity" your audience has. Together with your both willingness and knowledge to teach the materials.

- 4,591

$\varepsilon$-$\delta$(or$\varepsilon\text{-}\delta$), not$\varepsilon-\delta$. – Zev Chonoles Aug 01 '13 at 05:18