The operative term here is "free Abelian group". It basically encodes the idea of "multiplying a bunch of things by coefficients and adding them up". To echo @HallaSurvivor in the comments, the reason you might want this will depend on the specific application.

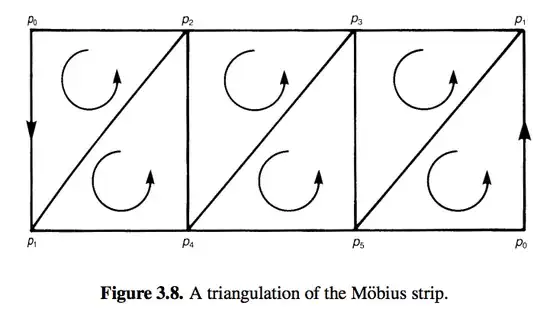

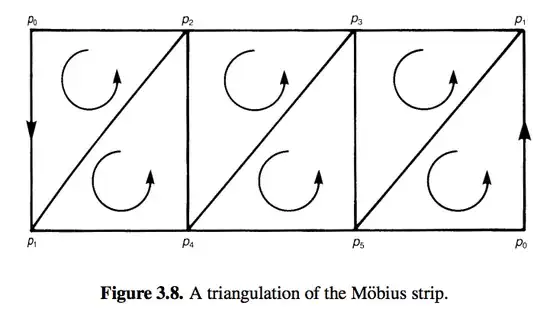

In the simplicial case, the interpretation is actually relatively intuitive. Let's take this example from a few sections later in Nakahara.

In the above diagram, we would like to say that the boundary of the entire strip consists of the edges $\langle p_1 p_3\rangle$, $\langle p_3 p_2\rangle$, $\langle p_2 p_0\rangle$, $\langle p_0 p_5\rangle$, $\langle p_5 p_4\rangle$, $\langle p_4 p_1\rangle$. Since the simplices are oriented by the order of their vertices, we could just say that this boundary is $$\langle p_1 p_3\rangle+\langle p_3 p_2\rangle+\langle p_2 p_0\rangle+\langle p_0 p_5\rangle+\langle p_5 p_4\rangle+\langle p_4 p_1\rangle$$ without ambiguity as to how the path is traversed, even if the order of these simplices were swapped.

Additionally (no pun intended), we would like to say that the total boundary of the strip is the sum of the boundary of the pieces. So when an edge is traversed one way in one piece and traversed the opposite way in another piece, as is the case with the edge $\langle p_1 p_2\rangle$ in $\langle p_0 p_1 p_2\rangle$ and $\langle p_1 p_4 p_2$, we could assign $\langle p_1 p_2\rangle$ from $\langle p_0 p_1 p_2\rangle$ with a positive sign, and the copy from $\langle p_1 p_4 p_2\rangle$ with a negative sign, so that when we take the boundary $\partial (\langle p_0 p_1 p_2\rangle+\langle p_1 p_4 p_2\rangle)$, the two terms (marked red) cancel,

\begin{align}

\partial (\langle p_0 p_1 p_2\rangle+\langle p_1 p_4 p_2\rangle) & = \partial \langle p_0 p_1 p_2\rangle+\partial\langle p_1 p_4 p_2\rangle\\

& = (\langle p_0 p_1\rangle + \color{red}{\langle p_1 p_2\rangle} - \langle p_0 p_2\rangle) + (\langle p_1 p_4\rangle - \langle p_2 p_4\rangle - \color{red}{\langle p_1 p_2\rangle} \\

& = \langle p_0 p_1\rangle - \langle p_0 p_2\rangle + \langle p_1 p_4\rangle - \langle p_2 p_4\rangle

\end{align}

There are deeper reasons why taking free Abelian groups generated by not very algebraic looking objects is useful. At this stage I would suggest taking it on faith that you could "multiply a bunch of things by coefficients and add them up", just to see how the computation shakes out and how the results can be interpreted, then try to convince yourself that there is an intuition behind the exercise after all.