1.2: Epsilon-Delta Definition of a Limit wrote that the $\delta$ we are seeking "can't contain $x$".

But at the top of page 51 in Writing Proofs in Analysis (2016), Jonathan M. Kane defined the $\delta$ as a function of $x$. Who's correct?

1.2: Epsilon-Delta Definition of a Limit wrote that the $\delta$ we are seeking "can't contain $x$".

But at the top of page 51 in Writing Proofs in Analysis (2016), Jonathan M. Kane defined the $\delta$ as a function of $x$. Who's correct?

That is just wrong. In a $\varepsilon-\delta$ proof of the fact that $\displaystyle\lim_{x\to a}f(x)=f(a)$, there can be no restriction of $\varepsilon$ and $\delta$ can only depend on $\varepsilon$ and on $a$. Nothing else.

No, nor $\delta$ nor $\epsilon$ can depend on $x$, and in fact it is quite easy to get rid of this dependence.

$x\to a$ means that $x$ gets close to $a$ or in mundane terms $x$ is almost the same value as $a$ and we can make $\delta$ depends on $a$ instead.

For instance if $a>0$ we can take $\delta_1=\frac a2$ and get $\frac a2\le x\le \frac{3a}2$

We now get $\frac {3a}2\le x+a\le \frac {5a}2$ and also $\frac{2}{5a}\le\frac 1{x+a}\le\frac{2}{3a}$ where bounds only depends on $a$ now.

Another possibility you often see is to take $\delta_1=1$ (for sake of simplicity) when $|a|>1$ instead of $\frac a2$.

So that $|x^2-a^2|<cst\times\epsilon$

Merging the two conditions leads to take some $\delta=\min(\delta_1,\delta_2)$.

Also many proofs like to arrive to a bare epsilon at the end so $\delta_2=\frac{\epsilon}{cst}$, this is the reason why you often see proofs like:

$$\text{let's take }\delta=\min(1,\frac{\epsilon}{12})\quad\text{ then ...}$$

$$u<1\implies \cdots <u^3<u^2<u<1$$

Making any polynomial in $|x-a|<1$ easily boundable since $|x-a|^n<1$ so we can bound by the sum of absolute values of coefficients of the polynomial.

e.g $|(x-a)^3+5(x-a)^2-2(x-a)+7|\le |x-a|^3+5|x-a|^2+2|x-a|+7<1+5+2+7=15$

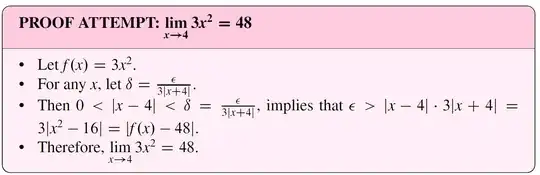

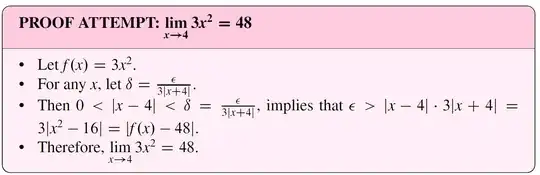

Please note that the section of the book Writing Proofs in Analysis quoted in this question is labelled a PROOF ATTEMPT. It is specifically presented in the book as an incorrect proof. The book goes on to discuss why the proof is incorrect, and then presents a correct proof. Seeing what can go wrong with a proof is an excellent way to learn what one needs to consider when writing a proof.

Jonathan Kane, author of "Writing Proofs in Analysis"

Are you familiar with quantifiers? To see what variables can depend on what in an $\epsilon-\delta$ proof (or really, any proof), write down the statement of what you need to prove and follow the order of the quantifiers.

In this case: $$\lim_{x\rightarrow a} f(x) = L \iff \forall \epsilon >0\, \exists \delta >0 \,\forall x\, \left(|x-a| < \delta \implies |f(x) - L| < \epsilon\right).$$

$\forall$ means "for all" and $\exists$ means "there exists". In English:

$\lim_{x\rightarrow a} f(x) = L $ means that for all $\epsilon > 0$ there exists $\delta > 0$ such that for all $x$, when $|x-a| < \delta$ then $|f(x) - L| < \epsilon$.

Since $\delta$ comes after $\epsilon$ in the expression above, $\delta$ can be chosen to depend on $\epsilon$. However, since $x$ comes after $\delta$, $\delta$ cannot be chosen to depend on $x$. So the cited proof is incorrect. (Notice though that in the screenshot you give, it is given as a "proof attempt" not a proof, so perhaps it is intentionally incorrect. I don't have access to the text so I don't know the context.)