Does $f'(x)=f(f(x))$ have any solutions other than $f(x)=0$?

I have become convinced that it does (see below), but I don't know of any way to prove this.

Is there a nice method for solving this kind of equation? If this equation doesn't have any non-trivial solutions, do you know of any similar equations (i.e. involving both nested functions and derivatives) that do have interesting solutions?

If we assume $f$ is analytic (which I will be doing from this point onward), then it must also be injective (see alex.jordan's attempted proof), and therefore has at most one root (call it $x_0$.)

We know $f'(x_0)=f(f(x_0))=f(0)$.

Claim: $f$ cannot have a positive root.

Suppose $x_0$ is positive. If $f(0)$ is negative, then for some sufficiently small $\delta>0$, $f(x_0-\delta)>0$. This implies there must be another root between $x_0$ and $0$, but $f$ has at most one root.

The same reasoning applies if $f(0)$ is positive.

If $f(0)=0$, then both $x_0$ and $0$ are roots. Thus, we conclude that $x_0$ cannot be positive.

Claim: $f$ cannot have zero as a root.

Suppose $x_0=0$. Since $f$ has at most one root, we know $f$ will be of constant sign on each of the positive and negative halves of the $x$ axis.

Let $a<0$. If $f(a)<0$, this implies $f'(a)=f(f(a))<0$, so on the negative half of the real line, $f$ is negative and strictly decreasing. This contradicts the assumption that $f(0)=0$. Therefore, $a<0\implies f(a)>0$, which then implies $f'(a)<0$.

But since $f'(a)=f(f(a))$, and $f(a)>0$, this implies $f(b)<0$ when $b>0$. Moreover, we know $f'(b)=f(f(b))$, and $f(b)<0 \implies f(f(b))>0$, so we know $f$ is negative and strictly increasing on the positive half of the real line. This contradicts the assumption that $f(0)=0$.

Claim: $f$ is bounded below by $x_0$ (which we've proved must be negative if it exists)

We know $f(x_0)=0$ is the only root, so $f'(x)=0$ iff $f(x)=x_0$. And since $f$ is injective, it follows that $f$ is either bounded above or bounded below by $x_0$ (if $f$ crossed $y=x_0$, that would correspond to a local minimum or maximum.) Since $f(x_0)=0$ and $x_0<0$, we know $x_0$ must be a lower bound.

Claim: $f$ is strictly decreasing.

Question B5 from the 2010 Putnam math competition rules out strictly increasing functions, so we know $f$ must be strictly decreasing.

Claim: $f$ has linear asymptotes at $\pm \infty$

Since $f$ is strictly decreasing and bounded below by $x_0$, we know $\lim_{x\rightarrow\infty}f(x)$ is well defined, and $\lim_{x\rightarrow\infty}f'(x)=0$. Since $f'(x)=0$ iff $f(x)=x_0$, it follows that $\lim_{x\rightarrow\infty}f(x)=x_0$.

$f''(x)=\frac{d}{dx}f'(x)=\frac{d}{dx}f(f(x))=f'(f(x))f'(x)$. Since $f'(x)<0$, we know $f$ is concave up. Thus, $\lim_{x\rightarrow -\infty}f(x)\rightarrow\infty$. This in turn implies $\lim_{x\rightarrow -\infty}f'(x)=\lim_{x\rightarrow -\infty}f(f(x))=\lim_{x\rightarrow \infty}f(x)=x_0$.

So $f$ goes to $x_0$ when $x\rightarrow\infty$, and approaches the asymptote $y=x_0\cdot x$ when $x\rightarrow-\infty$.

Claim: $x_0<1$

Consider the tangent line at $f(x_0)$. We know $f'(x_0)=f(0)$, so this line is given by $y=f(0)x-f(0)x_0$. Since $f$ is concave up, we know $f(x) > f(0)x-f(0)x_0$ for $x\neq x_0$, so $f(0) > -f(0)x_0$. And we can conclude $x_0<-1$.

Claim: $f$ must have a fixed point, $x_p$ (i.e. $f(x_p)=x_p$)

We know $f(x_0)=0$, $x_0<0$, and $f(0)<0$. Therefore, $f(x)-x$ has a root in the interval $(x_0,0)$.

This is all I have been able to prove. However, the existence of a fixed point turns out to be very useful in constructing approximate solutions.

Consider the following:

$$f(x_p)=x_p$$ $$f'(x_p)=f(f(x_p))=x_p$$ $$f''(x_p)=f'(f(x_p))f'(x_p)=f(f(f(x_p)))f(f(x_p))=x_p^2$$ $$f'''(x_p)=\cdots=x_p^4+x_p^3$$

If we are willing to put in the work, we can evaluate any derivative at the fixed point. I wrote a python program that computes these terms (unfortunately it runs in exponential time, but it's still fast enough to compute the first 20 or so terms in a reasonable amount of time). It leverages the following bit of information.

Suppose $f^{[n]}$ represents the nth iterate of $f$. e.g. $f^{[3]}=f(f(f(x)))$. Then we can derive the following recursive formula.

$$\frac{d}{dx}f^{[n]}=f'(f^{[n-1]})\frac{d}{dx}f^{[n-1]}=f^{[n+1]}\frac{d}{dx}f^{[n-1]}$$

And since we know the base case $\frac{d}{dx}f^{[1]}=f^{[2]}$, this lets us determine $(f^{[n]})'=f^{[n+1]}f^{[n]}\cdots f^{[3]}f^{[2]}$.

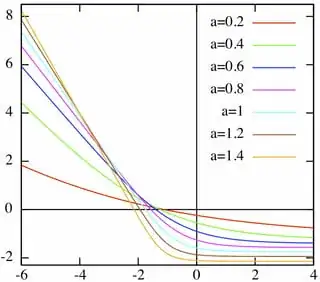

So, if we choose a fixed point, we can calculate the expected Taylor series around that point.

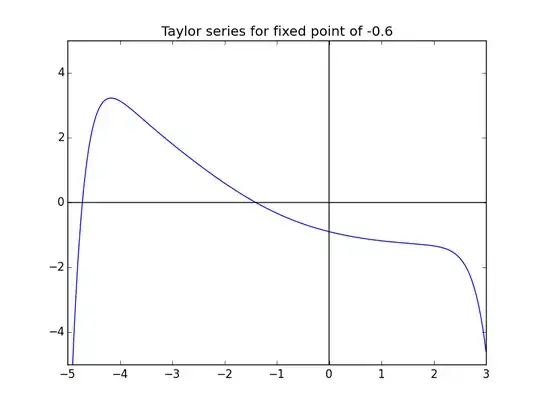

Here's the graph for the Taylor series with 14 terms, calculated with fixed point $-0.6$

You can clearly see the points where the series starts to fail (the radius of convergence doesn't seem to be infinite), but elsewhere the approximation behaves just as we would expect.

I computed $(P'(x)-P(P(x)))^2$, where $P$ is the Taylor polynomial, over the range where the series seems to converge, and the total error is on the order of $10^{-10}$. Moreover, this error seems to get smaller the more accurately you compute the derivative (I used $P'(x)\approx\frac{P(x+0.001)-P(x-0.001)}{0.002}$).

Being an analyst, I remember finding that problem much easier than many of the discrete math, contest-oriented problems on the Putnam =P

– Christopher A. Wong May 31 '13 at 22:02