Silverman in their book Rational Points on Elliptic Curves have a theorem;

Theorem 2.1: Let $C$ be a non-singular cubic curve $$C : y^2 = f (x) = x^3 + ax + bx + c.$$

(c) A point $P = (x, y) \neq \mathcal{O}$ on $C$ has order three if and only if $x$ is a root of the polynomial $$\psi_3 (x) = 3x^4 + 4ax^3 + 6bx^2 + 12c^x + 4ac − b^2.$$

(d) The curve $C$ has exactly nine points of order dividing three. These nine points form a group that is a product of two cyclic groups of order three.

We say that a point $P$ has order 3 if $[3]P = \mathcal{O}$, where $\mathcal{O}$ is the identity element, not necessarily the point at infinity. Then we have $[2]P = -P$ and looking at the $x$ coordinates $$x([2]P) = x(-P)=x(P)$$ then we can conclude that $x([2]P)=x(P)$ if $P \neq \mathcal{O}$

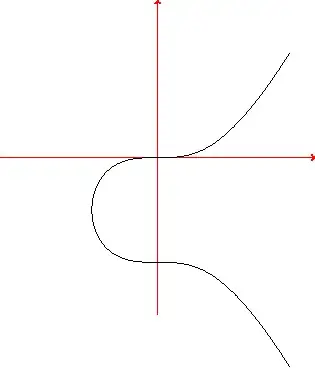

When we consider a curve like $y^2 +y = x^3$

If the two intersection points of the curve with the $y$-axis are inflection points then we will have the 6 points.

Where are all nine points on the curve geometrically?