This answer attempts to situate the issue in a dual view that historicaly has been capital, especially to Plücker for the discovery of his relationship that you surely know well. It is also how 19th century mathematicians have perceived/understood the power of duality because it could be explained through geometrical figures (and not with our present-day abstract algebraic notations), the only way to "convey" at that time what duality was about.

Disclosure : this isn't a general proof ; this answer, based on a final example (Fig. 4) is meant as a way to (more or less) follow the steps of Plücker, inserting the alignment of the three inflection points of a cubic curve into a more general context that brought him to a vast generalization.

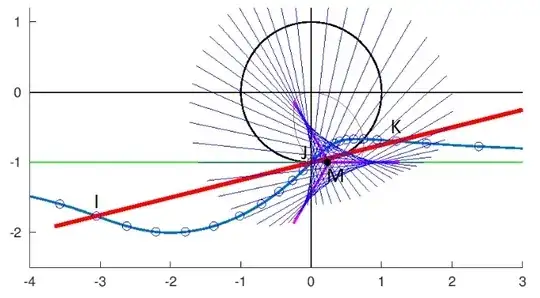

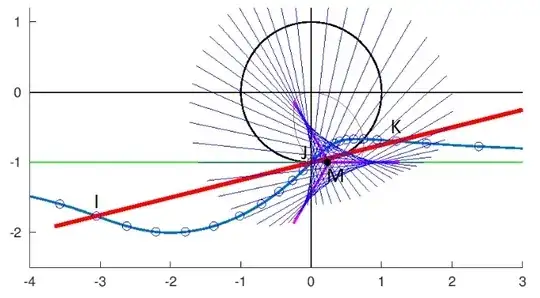

The objective is to understand Fig. 4.

In this respect, we need first a recall about the duality "poles $\leftrightarrow$ polar lines" (Fig. 1 and 2) ; it will allow us, in a second step (Fig. 3), to define the so-called "Polar Transform".

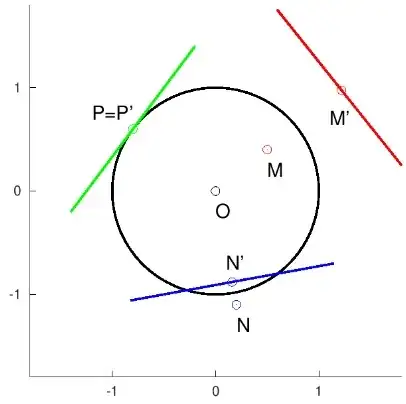

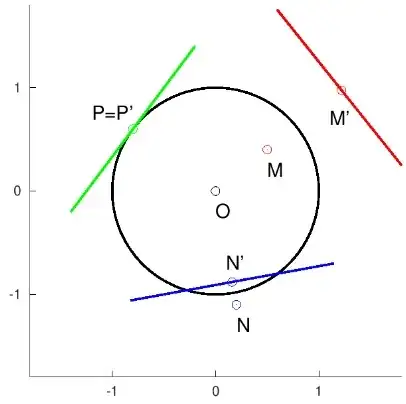

Let us consider the Euclidean plane with center $O$ and its unit circle. A point $M$ has a conjugate line called its polar line defined geometricaly in the following way ; the polar line of $M$ passes through $M'$ and is orthogonal to line $OM$ where $M'$ is the point of line $OM$ such that dot-product $\vec{OM}.\vec{OM'}=1$. The three different cases (point $M$ inside, outside and on unit circle are featured on figure $1$). $M$ is called the "pole" attached to its polar line.

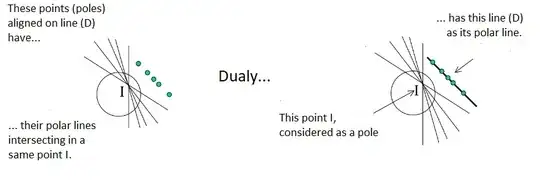

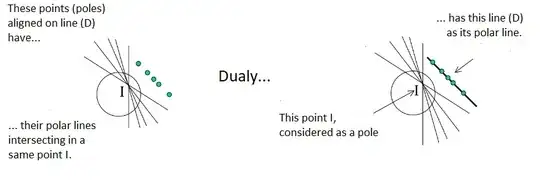

A fundamental property of duality is the connection between alignment of points and intersection of lines, illustrated on Fig. 2.

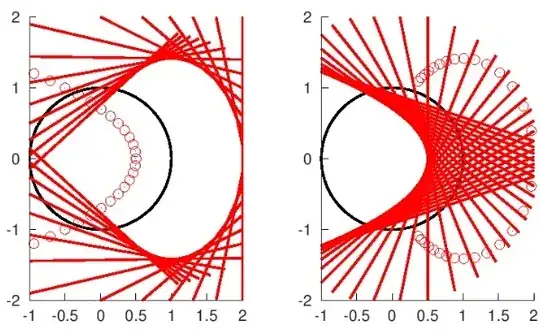

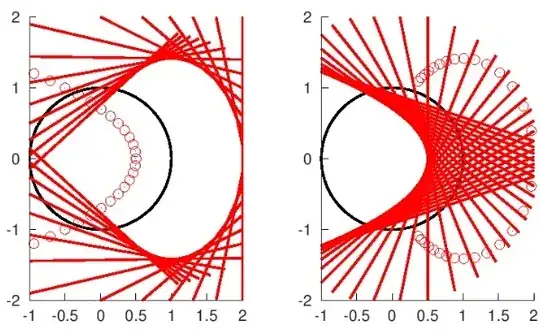

The concept of "polar transform" is explained using an example in Fig. 3.

Fig. 1 : When $P$ is on the unit circle, its polar line is the tangent line at $P$. One can consider the concept of polar line as a generalization of the concept of tangent.

Fig. 2 : Duality between points' alignment and (polar) lines intersection.

Fig. 3 : Duality between verbs "to describe" and "to envelope" : when points describe a curve (C) (here a parabola), their polar lines envelope a certain curve (C') (here an ellipse, partially materialized). In a dual way, when points describe (C'), their polar lines envelope (C) ! (C) and (C') are called reciprocal polar curves ; transform (C) $\leftrightarrow$ (C') is called "polar transform".

We have now the tools to understand Fig. 4 featuring the example of cubic curve $(C)$ with parametric equation :

$$(1+y)(x^2+y^2)-xy^2=0 \tag{1}$$

with 3 inflection points at finite distance and an asymptote $y=-1$.

Curve $(C)$ possesses an isolated point at the origin, that we will neglect. Please note that (1) can be converted into the following polar equation :

$$r=\frac{1}{\sin \theta (\tfrac12 \sin(2\theta)-1)}\tag{2}$$

Now turn to the legend of Fig. 4 which explains (almost) everything. The fact that inflection points are in correspondence with cusps is one of the most interesting observations that can be made.

Remarks :

-

- All the concepts introduced here (polar line, polar transform, etc...) can be given an algebraic form. See here. For example, if curve $(C)$ with current point $(x,y)$ decribed by parametric equations, one obtains the parametric equations of the polar transform under the form :

$$\begin{cases}x&=&\alpha(t)\\y&=&\beta(t)\end{cases} \ \ \to \ \ \begin{cases}X&=&-\beta'(t)/\delta(t)\\Y&=& \ \ \ \alpha'(t)/\delta(t)\end{cases}$$ $$\text{with} \ \delta(t)=\alpha(t)\beta'(t)-\alpha'(t)\beta(t).$$

In particular, the cubic and the deltoid can be represented resp. by the following parametric equations :

$$\begin{cases}x&=&\frac{t(1+t^2)}{(-1+t-t^2)}\\y&=&\frac{(1+t^2)}{(-1+t-t^2)}\end{cases} \implies \begin{cases}X&=&\frac{1-t^2}{(1+t^2)^2}\\Y&=&\frac{2t^3}{(1+t^2)^2}-1\end{cases}$$

-

- See this very interesting article, close to my approach.

-

- The thin red curve passing through the origin that can be seen on Fig. 4 is the inverse curve of $(C)$, which has as well a certain number of properties that would be too long to expand here.

Fig. 4 : A cubic curve $(C)$ (in blue), with some of its points and their polar lines ; the polar transform $(C')$ of $(C)$ (envelope of its polar lines) is a hypocycloid, more precisely a deltoid. The tangents at the 3 cusp/cuspidal points of $(C')$ (magenta color) are the polar lines of the 3 inflection points $I,J,K$ ; their common point $M$ is the pole of the line on which the inflection points are aligned.