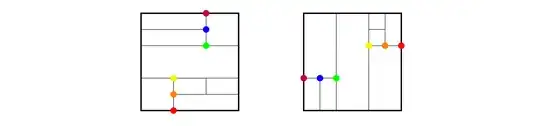

Given two tilings of a rectangle by other rectangles, say that they are equivalent if there is a bijection from the edges, vertices, and faces of the tilings which preserves inclusion. For instance, the following two tilings are equivalent (some corresponding vertices colored):

The number of non-equivalent rectangle tilings with $k$ tiles is given at A049021 in the OEIS.

Say that a tiling of a rectangle by $k$ other rectangles is prime if the only sub-rectangles in the tiling are individual tiles and the whole set.

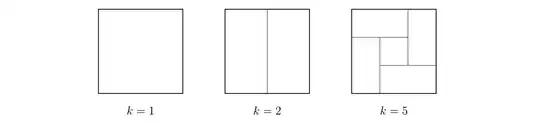

Here are the unique prime tilings for $k=1,2,5$ up to equivalence:

With some casework, one can verify that there are no prime tilings for $k=3,4,6$.

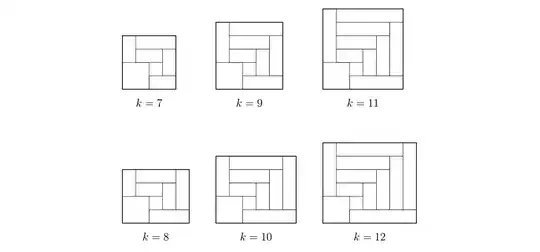

For all $k\ge 7$, there are at least two prime tilings. One follows the pattern shown below:

The other proceeds in a spiral pattern (in fact this construction yields the $k=5$ solution too):

It is not hard to check that these two constructions are distinct for all $k$.

How many non-equivalent prime tilings are there with k rectangles?

When $k=7$, I have verified that the above two constructions are the only ones possible, but the casework was extensive and I think approaches for $k$ beyond $9$ or $10$ will require new methods or computer-aided searches to be tractable.

This sequence starts $1,1,0,0,1,0,2,\ge2,\ge2,\ldots$. Even accounting for a possible initial term in the case $k=0$ and the possibility that I have missed a solution for $k=7$, there are no matches in the OEIS. I have started a draft for a new sequence, but I would like to be able to compute substantially more terms than this (and confirm my existing results) before adding anything. For comparison, A053740 gives the analogous sequence for prime dissections of a triangle into smaller triangles.

Some related discussion is at this post on /r/mathriddles.

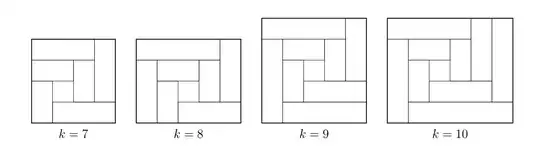

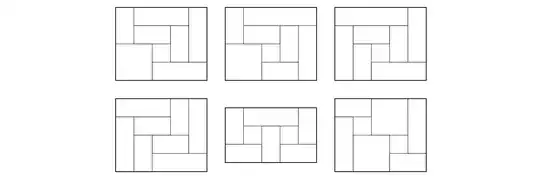

Edit: After a laborious manual classification, I believe there are exactly $6$ prime tilings in the $k=8$ case:

(Note that the horizontal symmetry of the example in the center of the second row is merely for visual appeal; the "heights" of either the SW or the SE rectangles could be varied without affecting equivalence.)

Edit 2021-02-15: These tilings are described in Tiling Rectangles With Rectangles (Chung et al., 1982), where they are called simple tilings. In the article, it is remarked that there are at least $c\cdot 2^{n/7}$ "essentially different" simple tilings with $n$ rectangles for some $c>0$ (and presumably only for $n\ge 7$?). It is also stated without proof that the number is bounded above by $20000^n$ given "a rather natural definition of equivalence". So the sequence grows exponentially, but it seems that the rate at which it does so is not very well pinned down.