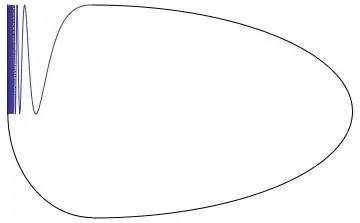

The Warsaw Circle is defined as the closed topologist's sine curve, with an additional arc attached at its free end point and one of the end points of the critical line:

Since we don't have an uncountable collection of disjoint open sets in the plane - such as the bounded component of its complement - we'll have to have an uncountable sequence $W_r$ such that if $r < s$ then $W_r$ is contained in the bounded component of $W_s^c$. Trying to draw it, it's actually kind of hard for me to tell for sure if it's true or not; it LOOKS true, but jeeze I think showing it with analytic, coordinate representations of each one is gonna be a bear.

Anyone really feeling it?

To be honest, I don't know the answer for the closed topologist's sine curve itself, either! Probably both are possible or both are impossible; have never seen it proved for either space.