Let $u \in \mathcal{C}_+^0([-1,1])$ be the normalized eigenvector of $T$ for the eigenvalue $r(T)$. One can indeed show the following result:

Theorem 1.

For every non-zero function $v_0$ in the positive cone, the iterates $\big(\frac{T}{r(T)}\big)^n v_0$ converge to a non-zero multiple of $u$ as $n \to \infty$.

Corollary 2.

Let $v_0$ be a non-zero function in the positive cone and define $v_n = \frac{Tv_{n-1}}{\|Tv_{n-1}\|}$ for each $n \ge 1$. Then $v_n$ converges to $u$ as $n \to \infty$.

Proof of Corollary 2.

Cearly, we have

$$

v_n = \frac{\big(\frac{T}{r(T)}\big)^n v_0}{\left\| \big(\frac{T}{r(T)}\big)^n v_0 \right\|}

$$

for each $n \ge 1$.

We know from Theorem 1 that there exists a number $\alpha > 0$ such that $\big(\frac{T}{r(T)}\big)^n v_0 \to \alpha u$. Hence, the norm $\left\| \big(\frac{T}{r(T)}\big)^n v_0 \right\|$ converges to $\|\alpha u\| = \alpha$, so $v_n \to \frac{\alpha u}{\alpha} = u$. $\square$

In order to prove Theorem 1, one can use general results from the spectral theory of positive operators on Banach lattices. To get this machinery to work, the first thing to do is to observe that the function space $\mathcal{C}^0([-1,1])$ is, in a sense, "too large" for the operator. Indeed, for each $f$ from this space, the function $Tf$ vanishes at $-1$ and $-1$.

So let $\mathcal{C}_0((-1,1))$ denote that set of all functions from $\mathcal{C}^0([-1,1])$ that vanish at $-1$ and $1$. Then the range of $T$ is contained in $\mathcal{C}_0((-1,1))$, so it suffices to prove the result for the restriction of $T$ to $\mathcal{C}_0((-1,1))$. Hence, we will assume from now on that $T$ is defined on the slightly smaller space $\mathcal{C}_0((-1,1))$.

The space $\mathcal{C}_0((-1,1))$ is a Banach lattice (with respect to the usual pointwise ordering) and the operator $T$ on it is positive (i.e. it maps the cone into the cone).

Remark. The space $\mathcal{C}^0(([-1,1])$ is a Banach lattice, too, and $T$ is a positive operator on it, too; the reason why this space is not good to work with will be explained below.

In order to apply general results from the literature, we need the following terminology:

Definition 3.

Let $E$ be a Banach lattice (e.g., the space $\mathcal{C}_0((-1,1))$).

(a) A vector subspace $I$ of a Banach lattice $E$ is called an ideal if, for all $f,g \in E$ such that $g \in I$ and $\lvert f \rvert \le g$, we have $f \in I$.

(b) A positive linear operator $S$ on $E$ is called irreducible if the only closed $S$-invariant ideals in $E$ are $\{0\}$ and $E$. (Here, an ideal $I$ is said to be $S$-invariant if $SI \subseteq I$.)

In the Banach lattice $\mathcal{C}_0((-1,1))$ an explicit description of all closed ideals is known: they are precisely the sets of the form

$$

\{f \in \mathcal{C}_0((-1,1)): \, f|_A = 0\},

$$

where $A$ is any closed subset of $(-1,1)$. This can be seen as follows:

Proof that each closed ideal can be described in this way: The fact that each such set is a closed ideal is obvious.

To see that the converse implication holds, one can, for instance, refer to [Mey91, Proposition 2.1.9]. There, a similar description of all closed ideals in the space $\mathcal{C}(K)$ for a compact Hausdorff space $K$ is given. We can simply apply this description to $\mathcal{C}^0([-1,1])$ (which would be denoted as $\mathcal{C}([-1,1])$ in the notation of [Mey91]). Since $\mathcal{C}_0((-1,1))$ is clearly a closed ideal in $\mathcal{C}^0([-1,1])$, it follows that each closed ideal $I$ in $\mathcal{C}_0((-1,1))$ is also a closed ideal in $\mathcal{C}^0([-1,1])$; hence, $I$ has the description claimed above. $\square$

With this description of closed ideals at hand, it is easy to show that our operator $T$ is irreducible. In fact, if $f$ is a non-zero function in the cone of $\mathcal{C}_0((-1,1))$, and if we use the notation

$$

\{g > 0\} := \{x \in (-1,1): \, g(x) > 0\}

$$ for any real-valued function $g$ defined on $(-1,1)$, then we have

$$

\{f > 0\} \subseteq \{Tf > 0\} \subseteq \{T^2f > 0\} \subseteq \{T^3f > 0\} \dots,

$$

and the (monotone) union of those sets equals the entire set $(-1,1)$. These observations are consequences of the definition of $T$.

Consequently, our operator $T$ has the following property:

Proposition 4. For each interger $n \ge 1$, the power $T^n$ is irreducible.

Remark. The fact that $T$ is irreducible and compact implies that $r(T) > 0$ by a general theorem of de Pagter [dPa86, Theorem 3]. However, I don't know whether the general theory is particularly helpful to determine the precise value of $r(T)$.

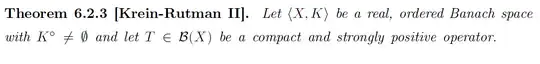

Now we apply the quite have machinery of infinite dimensional Perron-Frobenius theory, which yields the following result:

Proposition 5. Our operator $T$ has the following properties:

(a) The eigenspace $\ker(r(T) - T)$ is one-dimensional and spanned by a function $u$ which is strictly positive on $(-1,1)$.

(b) The dual eigenspace $\ker(r(T) - T)'$ is spannend by a strictly positive functional $\varphi$ in the dual space of $\mathcal{C}_0((-1,1))$ (where strictly positive means that $\langle \varphi, f\rangle > 0$ for every non-zero vector $f$ in the cone of $\mathcal{C}_0((-1,1))$).

(c) The eigenvalue $r(T)$ of $T$ is algebraically simple.

(d) Each eigenvalue of $T$ of modulus $r(T)$ is the product of $r(T)$ with a root of unity.

Proof.

Assertions (c) and (d) follow, for instance, from [Gro95, Theorem 5.3]. Assertion (b) now follows from [Gro95, Proposition 5.1]. Finally, assertion (a) follows from [Gro95, Theorem 5.2]. Note that, in order to translate the latter reference to assertion (a) above, one needs to observe that the quasi-interior points of the cone in $\mathcal{C}_0((-1,1))$ are precisely those functions $f$ that satisfy $f(x) > 0$ for each $x \in (-1,1)$. $\square$

Remark. The OP has already observed in the question that the eigenspace $\ker(r(T) - T)$ is one-dimensional. Part (a) of the previous proposition actually shows that this fact can also be derived from general infinite dimensional Perron-Frobenius theory.

For the previous proposition, we only needed $T$ itself to be irreducible, but not necessarily its powers. For the next result, we finally use the irreducibility of the powers of $T$:

Proposition 6.

The operator $T$ does not have any eigenvalue of modulus $r(T)$, except for $r(T)$ itself.

Proof.

Let us consider the operator $S := T/r(T)$. If $\lambda \not= 1$ is an eigenvalue of modulus $1$ of this operator, then it is a root of unity by Proposition 5(d). Hence, there exists an integer $n \ge 1$ such that $\lambda^n = 1$. But this implies that $1$ is an eigenvalue of $S^n$ of geometric multiplicity at least $2$. This is a contradiction: since $S$ is irreducible, the eigenspace $\ker(1-S)$ has dimension $1$ [Gro95, Theorem 5.2]. $\square$

Now, we can finally prove Theorem 1:

Proof of Theorem 1.

It suffices to prove the theorem for $v_0 \in \mathcal{C}_0((-1,1))$.

Set $S := T/r(T)$, and let $P$ denote the spectral projection of $S$ for the eigenvalue $1$. It follows from Proposition 5(a)-(c) that $P$ is a rank-$1$-projection that is given by $Pf = \langle \varphi, f \rangle u$ for all $f \in \mathcal{C}_0((-1,1))$ (provided that $\varphi$ is scaled such that $\langle \varphi, u\rangle = 1$).

According to Proposition 6, $S$ has no eigenvalues on the unit circle except for $1$. Hence, the powers $S^n$ converge to $P$ with respect to the operator norm as $n \to \infty$. In particular, for each $v_0 \in \mathcal{C}_0((-1,1))$, the sequence $(S^n v_0)$ converges to $Pf = \langle \varphi, v_0\rangle u$. $\square$

Remarks.

(a) The reason why we considered the space $\mathcal{C}_0((-1,1))$ rather than $\mathcal{C}^0([-1,1])$ is that the operator $T$ is not irreducible on $\mathcal{C}^0([-1,1])$ (in fact, the space $\mathcal{C}_0((-1,1))$ itself is a closed ideal in $\mathcal{C}^0([-1,1])$ which is invariant under $T$).

(b) The arguments shown above use quite general and abstract tools from operator theory on Banach lattices. For the concrete operator under consideration, it might be possible to find a more elementary proof (although I personally don't know one). Still, those general techniques have the advantage that they can be applied in a large variety of situations and that they yield rather strong qualitative results.

References:

[Gro95]: J. J. Grobler: Spectral theory in Banach lattices, 1995. [link to zbMATH]

[Mey91] Peter Meyer-Nieberg: Banach lattices, 1991. [link to zbMATH]

[dPa86]: Ben de Pagter: Irreducible compact operators, 1986. [link to zbMATH]