Posting this as an answer, because I still want more feedback from the OP. And I need to post pictures to get that so it has to be an answer.

My idea is to use orbits of a Coxeter group. So if $G$ is a finite group generated by orthogonal reflections through the origin, and $x\in\Bbb{R}^3$ a carefully chosen "initial point", then the set of vectors

$$C=\{g(x)\mid g\in G\}$$

will have some nice properties that I describe below:

- In 3D we can use three planes, $H_1,H_2,H_3$, (= the walls of a Weyl chamber) such that $G$ is then generated by the reflections $s_i, i=1,2,3,$ w.r.t. these walls.

- Without loss of generality we can assume that $x$ is within that Weyl chamber (examples below). When that happens it is easy prove that the minimum distance between two points of $C$ is equal to the distance between $x$ and the closest of the points $s_i(x),i=1,2,3$. This is obvious to anyone well versed in Coxeter groups.

- So if we select $x$ so that it is equidistant from all the three walls, then we know that $x$ has three closest neighbors $s_i(x), i=1,2,3$.

- The elements of $G$ are all distance preserving (i.e. elements of $O(3)$). Therefore the conclusion of the previous bullet applies more generally. Every element of $C$ has three equidistant closest neighbors. The closest neighbors of $g(x)$ are $g(s_i(x)), i=1,2,3$.

- The generators $s_1,s_2,s_3$ are all reflection w.r.t a plane, so they reverse handedness (have determinants $=-1$). It follows that $G$ has a subgroup $H$ of index two consisting of the elements of $G\cap SO(3)$. Observe that none of the generators $s_i$ are in $H$. This is important.

- We then split $C$ into two parts:

$$C_+=\{g(x)\mid g\in H\}\qquad\text{and}\qquad C_-=\{g(x)\mid g\notin H\}.$$ Observe that the closest neighbors of any vector $y\in C$ belong to the opposite half. Therefore we get a desirable construction by drawing the vectors related to $C_+$ pointing out, and those related to $C_-$ pointing in.

- Because $C$ is a single orbit of a subgroup of $O(3)$ the resulting collection is homogeneous. Meaning that by rotating the space in an appropriate way we can bring any vector to the position of $x$ in such a way that the entire constellation $C$ is rotated back to itself $-$ the constellation looks alike around any one of its points.

As an example let us consider the Coxeter group of symmetries of a cube. These are orthogonal transformations of the form

$$(x_1,x_2,x_3)\mapsto (\pm x_{\sigma(1)},\pm x_{\sigma(2)},\pm x_{\sigma(3)})$$

with all $8$ sign combos and all $6$ permutations $\sigma\in S_3$ for a total of $48$ elements in $G$. This turns out to be a Coxeter group (take my word for it for now) generated by the reflections

- $s_1(x,y,z)=(y,x,z)$, the reflection w.r.t. the plane $H_1:x=y$,

- $s_2(x,y,z)=(x,z,y)$, the reflection w.r.t. the plane $H_2:y=z$,

- $s_3(x,y,z)=(x,y,-z)$, the reflection w.r.t. the plane $H_3:z=0$.

The (fundamental) Weyl chamber then consists of the points with coordinates $(x,y,z)$

satisfying $x\ge y\ge z\ge0$. The point $x=(1+2\sqrt2,1+\sqrt2,1)$ is then at distance

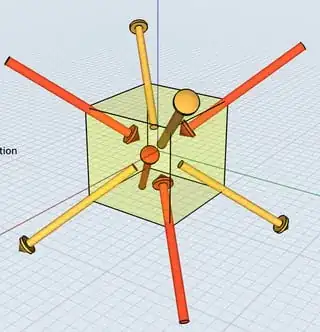

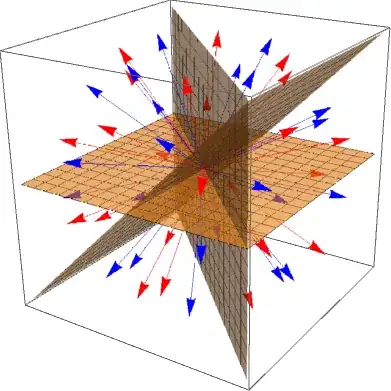

$1$ from all the planes $H_i$. It may be easier to verify that $d(s_i(x),x)=2$ for all $i=1,2,3$. Anyway, the resulting picture looks like the following:

The vectors in $C_+$ are red and those in $C_-$ are blue. I could reverse the direction of the blue arrows, but then the blue arrowheads would form an uninformative lump at the origin. I'm afraid the picture may not be very intuitive.

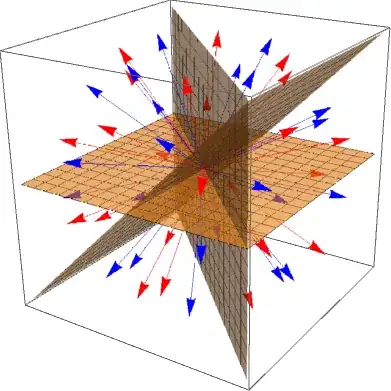

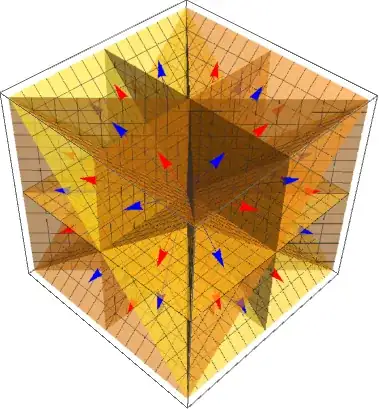

Below there is another image of the same configuration. This time I added the three walls $H_1,H_2,H_3$. The fundamental Weyl chamber is the pyramid shape in the front. You see the red vector $x$ inside it, its arrowhead equidistant from the three walls.

If $g\in G$ and $H$ is a wall of the chamber around $x$, then $g(H)$ is a wall of the chamber containing $g(x)$.

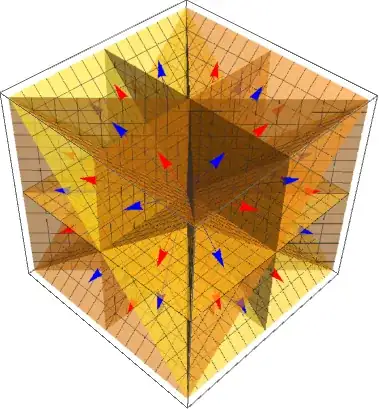

In the next picture we see all the $48$ chambers. Alltogether there are nine planes of reflective symmetry, and these are the walls separating the chambers. I tried to pick the view point in such a way that you see an octant split into six chambers in the front. Each chamber within an octant has the absolute values of the coordinates are sorted in one of the six possible specific ordes.

The homogeneity of the constellation manifests itself in several ways. All the chambers have the same shape, each has three walls, each contains one vector, red or blue, according to the rule that every time you cross a wall to the adjacente chamber the color changes.

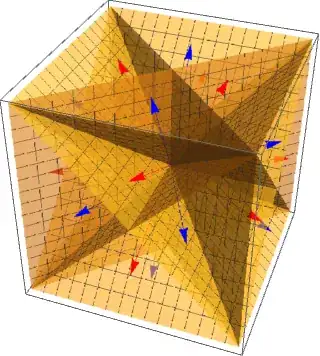

A smaller example of $24$ vectors can be gotten by using the group of $24$ symmetries of a regular tetrahedron. Imagine that the four vertices of a tetrahedron are at the points $(\pm a,\pm a,\pm a)$ where we this time only allow an even number of minus signs (so two or none). The corresponding Coxeter group is a subgroup of the previous group of transformations, where this time we only allow an even number of sign changes. The generators $s_1$ and $s_2$ from above can be reused, but I replace $s_3$ with

$$

s_3':(x,y,z)\mapsto (x,-z,-y)

$$

reflecting w.r.t. the plane $H_3':y=-z$. This time there are only six walls altogether (because reflections w.r.t. the coordinate planes are no longer symmetries). We readily see that the initial vector $x=(2,1,0)$ is at distance

$\sqrt2/2$ from all the walls $H_1,H_2,H_3'$.

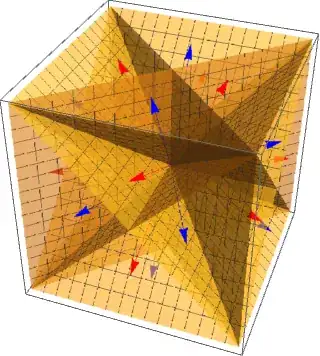

The picture with chamber, walls and blue/red arrows looks like the following.

The remark about the color changing every time we cross the wall from one chamber to an adjacent one applies. This time we have four chambers on each face of the cube.