There are at least five ways to multiply two natural numbers $a$ and $b$ given as integer points $A$ and $B$ on the number line by geometrical means. Two of them include counting, the others are purely geometric. I wonder (i) if there are other ways and (ii) how to deeply understand the interrelationship between the different methods (i.e. recipes).

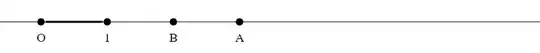

Let $A,B$ be two integer points on the line $O1$:

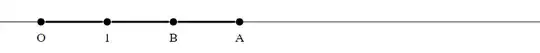

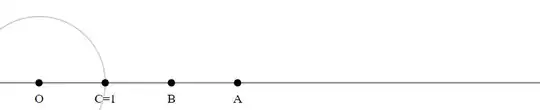

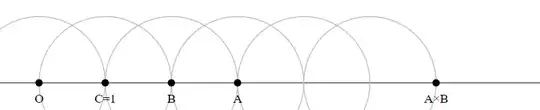

Method 1

- Count how often the unit length $|O1|$ fits into $|OA|$. Let this number be $a$ (here $a = 3$).

Draw a circle with radius $|OB|$ around $B$.

Let $C$ be the (other) intersection point of this circle with the line $O1$.

Draw a circle with radius $|OB|$ around $C$.

Do this $a-1$ times.

The last intersection point $C$ is the product $A \times B$.

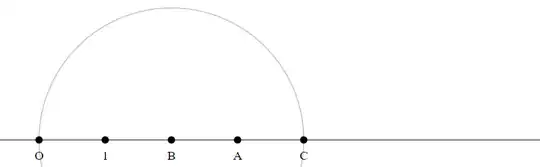

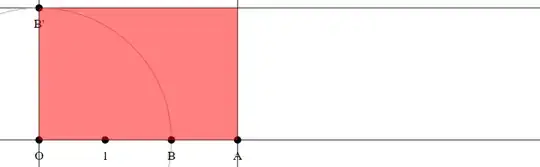

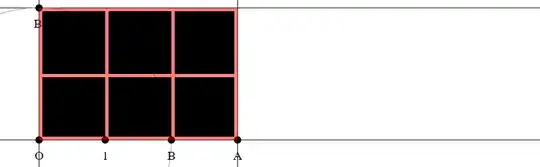

Method 2

- Construct a rectangle with side lengths $|OA|$, $|OB|$.

- Count how often the unit square (with side length $|O1|$) fits into the rectangle. Let this number be $c$ (here $c=6$).

Draw a circle with radius $|O1|$ around $0$.

Let $C$ be the intersection point of this circle with the line $O1$.

Draw a circle with radius $|O1|$ around $C$.

Do this $c$ times.

The last intersection point $C$ is the product $A \times B$.

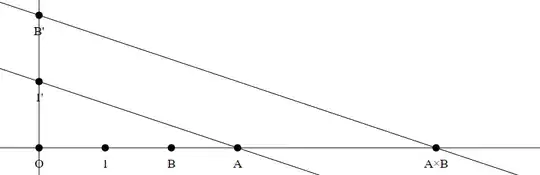

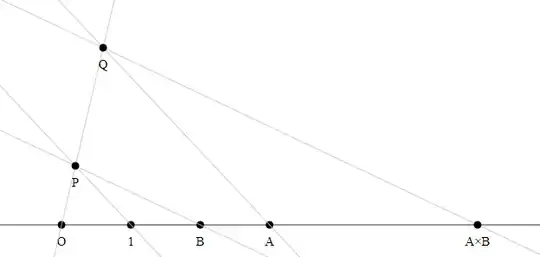

Method 3

Construct the line perpendicular to $O1$ through $O$.

Construct the points $1'$ and $B'$.

Draw the line $1'A$.

Construct the parallel to $1'A$ through $B'$.

The intersection point of this parallel with the line $O1$ is the product $A \times B$.

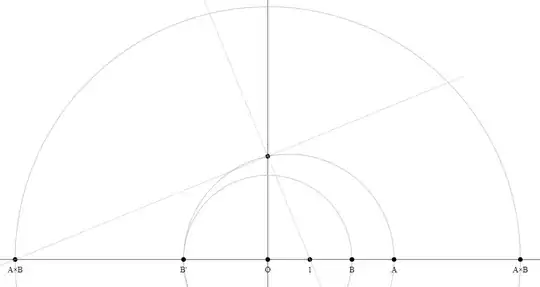

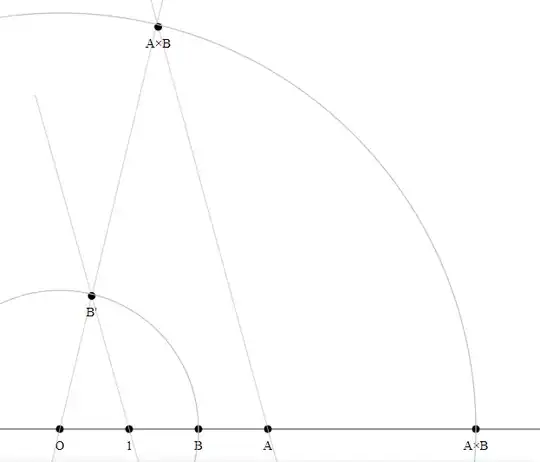

Method 4

Construct the perpendicular line to $O1$ through $O$.

Construct the point $1'$.

Construct the circle through $1'$, $A$ and $B$.

The intersection point of this circle with the line $O1'$ is the product $A \times B$.

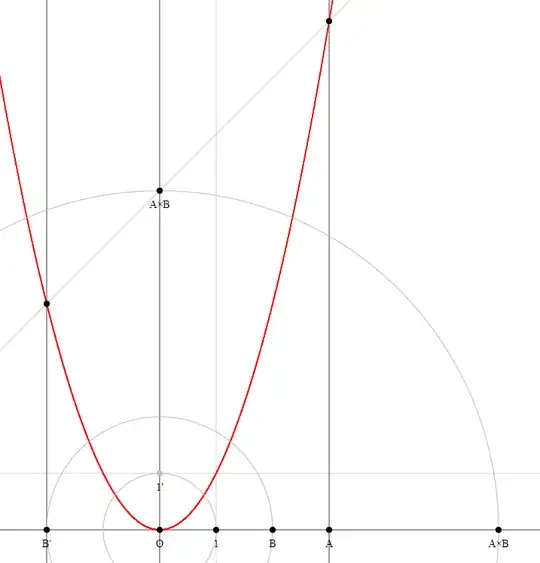

Method 5

This method makes use of the parabola, i.e. goes beyond compass-ruler constructions.

Construct the unit parabola $(x,y)$ with $y = x^2$.

Construct $B'$.

Construct the line perpendicular to $O1$ through $A$.

Construct the line perpendicular to $O1$ through $B'$.

Draw the line through the intersection points of these two lines with the parabola.

The intersection point of this line with the line $O1'$ is the product $A \times B$.

For me it's something like a miracle that these five methods – seemingly very different (as recipes) and not obviously equivalent – yield the very same result (i.e. point) $A \times B$.

Note that the different methods take different amounts $\sigma$ of Euclidean space (to completely show all intermediate points and (semi-)circles involved, assuming that $a >b$):

Method 1: $\sigma \sim ab^2$

Method 2: $\sigma \sim ab$

Method 3: $\sigma \sim ab^2$

Method 4: $\sigma \sim a^2b^2$

Method 5: $\sigma \sim a^3b$

This is space complexity. Compare this to time complexity, i.e. the number $\tau$ of essential construction steps that are needed:

Method 1: $\tau \sim a$

Method 2: $\tau \sim ab$

Method 3: $\tau \sim 1$

Method 4: $\tau \sim 1$

Method 5: $\tau \sim 1$

From this point of view method 3 would be the most efficient.

Once again:

I'm looking for other geometrical methods to multiply two numbers given as points on the number line $O1$ (is there one using the hyperbola?) and trying to understand better the "deeper" reasons why they all yield the same result (i.e. point).

Those answers I managed to visualize I will add here: