Informal Answer

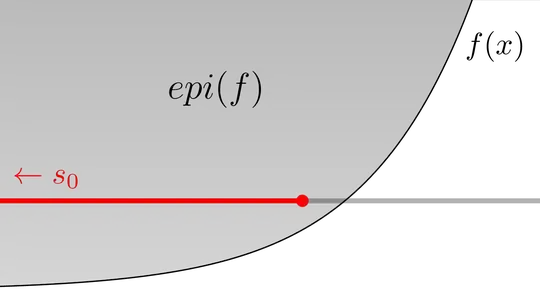

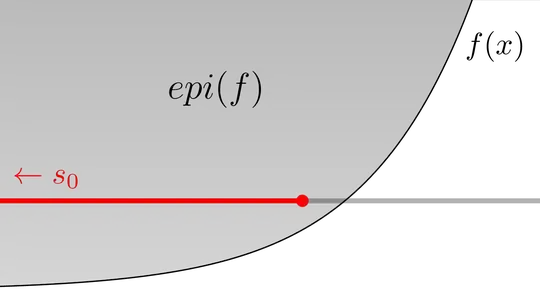

The epigraph of an increasing function $f$ has the property that $\mathop{epi}(f) = \mathop{epi}(f) + \Bbb R_-\times \{0\}$, i.e. it contains its own translation leftwards. In other terms:

A function $f:\Bbb R \to \Bbb R$ is increasing iff $\mathop{epi}(f)$ is star-convex with the vantage point "$(-\infty,0)$".

Definitions:

- Intervals $\Bbb R_- = (-\infty,0]$, $\ \Bbb R_+ = [0,\infty)\ $ and $\ \Bbb R_{++} = (0,\infty)$.

- Minkowski sum $S + \Bbb R_-\times \{0\} = \{(x-\alpha,y)\in \Bbb R^2: (x,y)\in S, \alpha \in \mathbb R_-\}$

- A set $S\subset \Bbb R^n$ is star-convex if there is a point $s_0$ such that for any point $s\in S$ the line segment between $s$ and $s_0$ is contained in $S$. The point $s_0$ is then called the vantage point and $S$ is said to be star-convex at $s_0$.

Note that a set might have multiple vantage points, convex sets provide an extreme example of it (a related post):

A set $S$ is convex iff it is star-convex at every point $s_0\in S$.

Usually the point $s_0$ is required to be a point in $S$. However, in order to be able to characterize the property $S=S+\Bbb R_-\times \{0\}$ as that $S$ is star-convex, we need to augment the definition of star-convexity by allowing for a vantage point to be a "point at infinity" in a certain directions. I will formalize this below.

Oriented extended Euclidean plane

Let me define an "oriented" version of the extended Euclidean plane:

Let equivalence relation $\sim$ be defined on the set $H = \Bbb R^2 \times \Bbb R_+ \setminus \{(0,0,0)\}$ so that points $(a_1,b_1,c_1)$ and $(a_2,b_2,c_2)$ form $H$ are in relation iff $(a_1,b_1,c_1)=(a_2t,b_2t,c_2t)$ for some $t\in \Bbb R_{++}$. We say that the quotient space $H/_{\sim}$ is the oriented extended Euclidean plane. For every point $(a,b,c)\in H$ we denote its quotient class as $[a,b,c]\in H/_\sim$. We distinguish two types of points in $H/_\sim$:

- A point $[x,y,1]$ represents the Euclidean space point $(x,y)\in\Bbb R^2$, we write then $[x,y,1]\sim (x,y)$;

- A point $[a,b,0]$, where $(a,b)\in \Bbb R^2 \setminus \{(0,0)\}$ represents an oriented point at infinity.

Note: Unlike in the in the conventional extended Euclidean plane, here $[a,b,0]$ and $[-a,-b,0]$ represent two different points (that is why I chose the adjective "oriented"). Hence, every line has two oriented points at infinity.

Generalized star-convexity:

For a set $S\subset \mathbb R^2$ we denote $[S]\subset \Bbb R^3$ the set of all points $(a,b,c)\in H$ such that $[a,b,c]=[x,y,1]$ for some $(x,y)\in S$; and $S^\infty\subset \Bbb R^3$ the set of all the points $(a,b,0) \in \mathop{cl}[S]$ (meaning that $(a,b,0)$ is a limit point of $[S]$ in the Euclidean space $\Bbb R^3$).

We say that $S\subset \Bbb R^2$ is star-convex at $[a,b,0]\in H/_\sim$ if and only if $[S] \cup S^\infty \subset \Bbb R^3$ is star-convex at $(a,b,0)\in\Bbb R^3$.

Or equivalently:

$S\subset \Bbb R^2$ is star-convex at $[a,b,0]\in H/_\sim$ iff for any $u \in [S]$ the half-open line segment connecting $u$ (included) and $(a,b,0)$ (excluded) is contained in $[S]$.

Formal Answer

A function $f:\Bbb R \to \Bbb R$ is increasing iff $\mathop{epi}(f)$ is star-convex at the oriented point at infinity $[-1,0,0]$.

Note: In fact $\mathop{epi}(f)$ of an increasing function is generalized star convex at any oriented point at infinity $[-a,b,0]$ with $(a,b)\in \Bbb R_+^2$.

Discussion: Formalizing in which sense $\mathop{epi}(f)$ of an increasing function is star-convex is somewhat cumbersome. The reason why I find it meaningful is thanks to the relation between star-convex sets and convex sets. I also believe that it can shed light on how epigraph of functions with positive third-order derivative could be characterized, as I'm trying to do:

Geometric characterization of functions with positive third derivative.