I recently learned the following pleasant fact. (It was in the proof of Proposition 3.1 of this paper - but don't worry, there's no model theory in this question.)

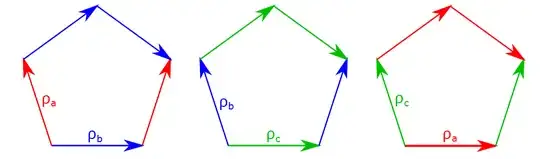

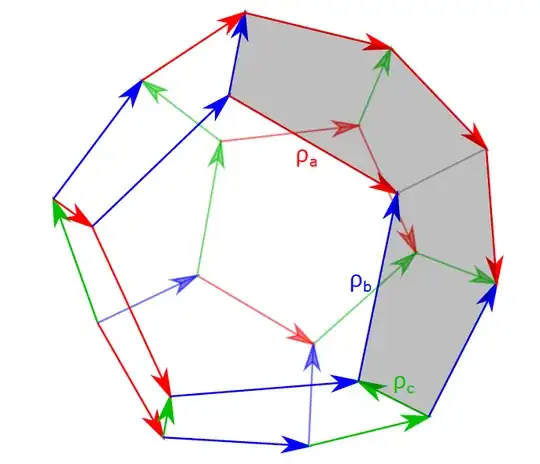

Let $G$ be a group, and let $a,b,c\in G$. If $aba^{-1} = b^2$, $bcb^{-1} = c^2$, and $cac^{-1} = a^2$, then $a = b = c = e$. Put another way, the group defined by generators and relations $\langle a,b,c \mid aba^{-1} = b^2, bcb^{-1} = c^2, cac^{-1} = a^2 \rangle$ is the trivial group.

I came up with the following elementary, but ugly, proof:

The relations can be rewritten as (1) $ab = b^2a$, (2) $bc = c^2b$, (3) $ca = a^2c$.

Using (1), (2), and (3), we can rewrite $a^4bc = a^4c^2b = c^2ab = c^2b^2a$.

But we can also rewrite $a^4bc = b^{16}a^4c = b^{16}ca^2 = c^{2^{16}}b^{16}a^2$.

So $c^{2^{16}}b^{16}a^2 = c^2b^2a$. This implies $a = b^{-16}c^{2-2^{16}}b^2$.

Substituting for $a$ in (1) above, $b^{-16}c^{2(1-2^{15})}b^3 = b^{-14}c^{2(1-2^{15})}b^2$, and cancelling from both sides, $c^{2(1-2^{15})}b = b^{2}c^{2(1-2^{15})}$.

But now by (2), we have $bc^{1-2^{15}} = b^{2}c^{2(1-2^{15})}$, and $b = c^{2^{15}-1}$. But then $b$ and $c$ commute, so $bcb^{-1} = c^2$ implies $c = c^2$, and $c = e$. It then follows easily that $a = b = c = e$.

Question: Is there a better way to see this? i.e. a more abstract proof, or at least one that doesn't involve manipulating words of length $2^{16}$?