This will be my another possible answer to Claim that Proposition 09 is Equivalent to Van Abuel's Theorem , So follow the Given steps to understand the Situation:

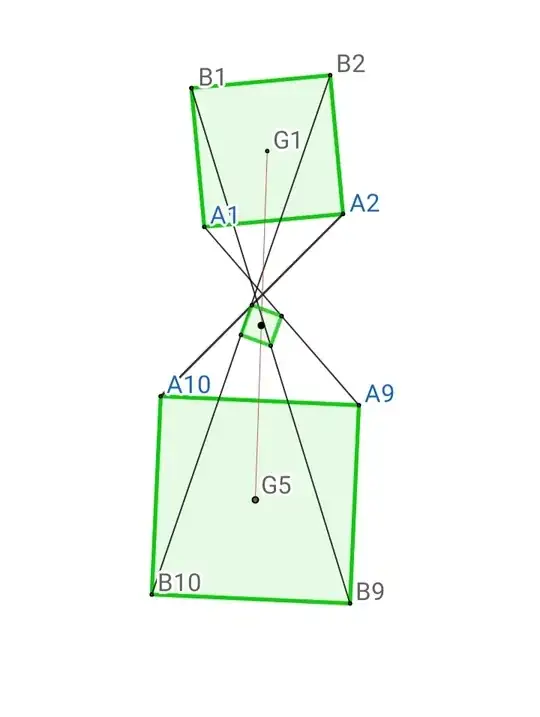

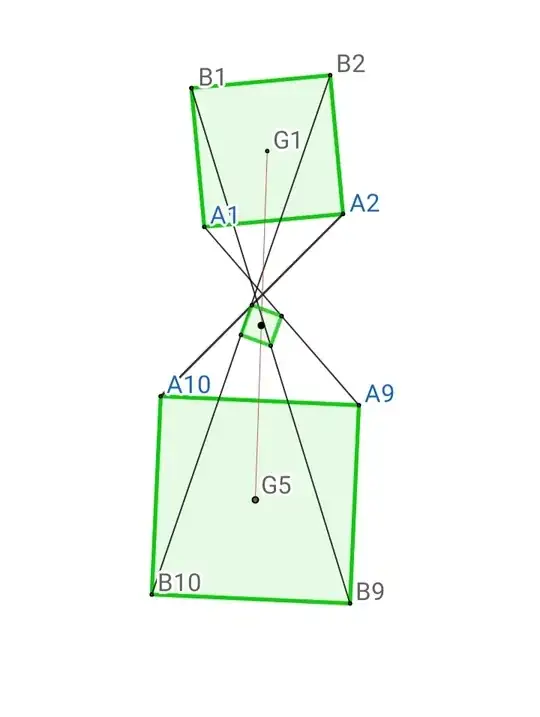

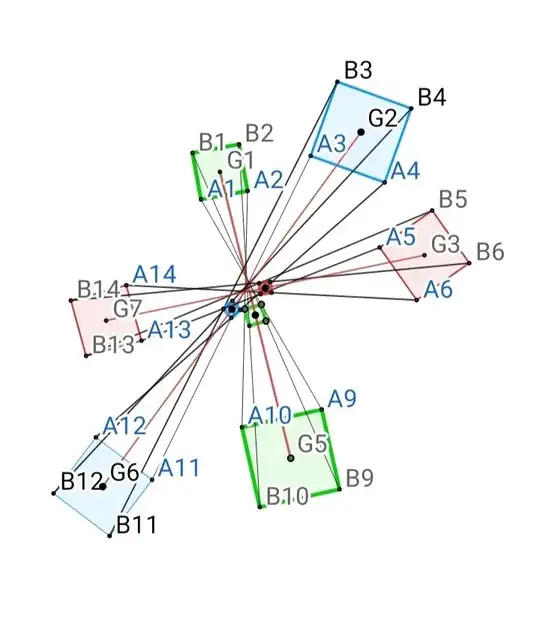

Step 01:Take Two Squares A1A2B1B2 and A9A10B9B10 then m(A2,A10) ;m(A1,A9) ; m(B2,B10); m(B1,B9) makes Green Square as shown in figure:

Let G1,G5 be center of Square A1A2B1B2 and A9A10B9B10 then m(G1,G5) will be center of small green Square.

Let G1,G5 be center of Square A1A2B1B2 and A9A10B9B10 then m(G1,G5) will be center of small green Square.

Step 02: We will name small green Square formed in step 01 as "Midpoint of Square A1A2B1B2 and A9A10B9B10".

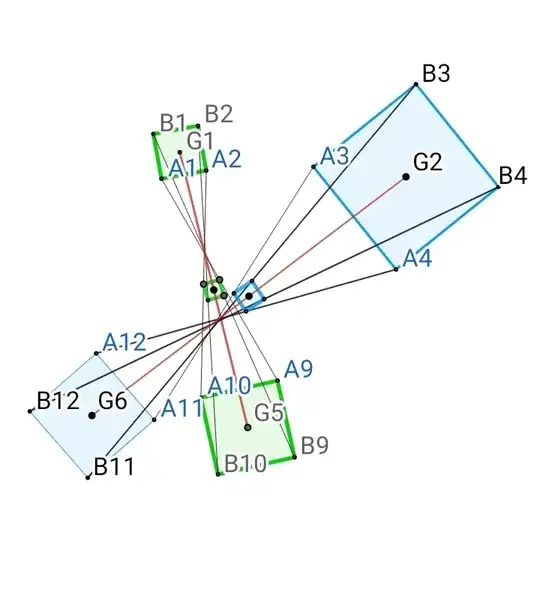

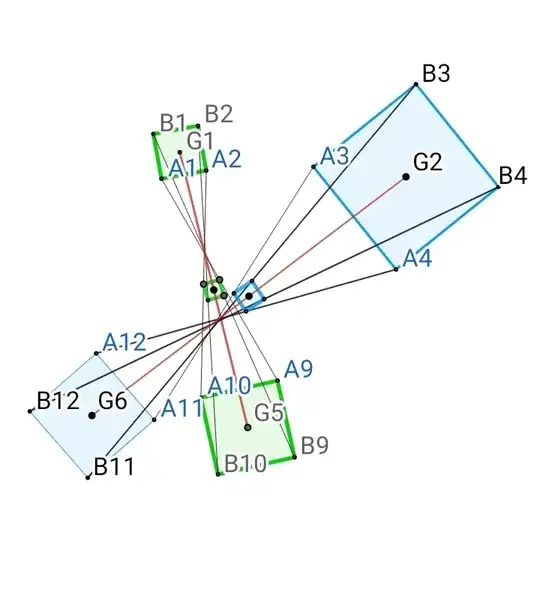

Step03: Similarly make "midpoint of Square of A3A4B3B4 and A11A12B11B12" as Shown in this figure:

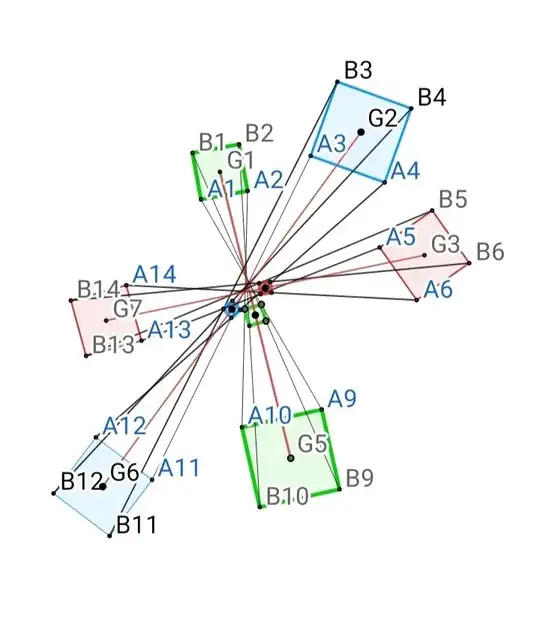

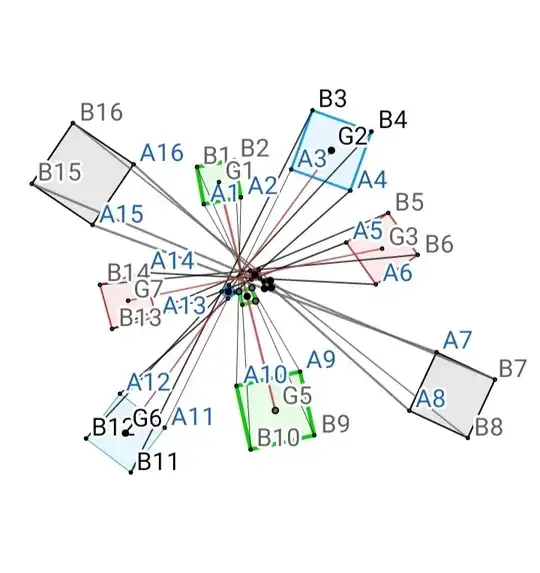

Step04: Now take again "midpoint of Square A5A6B5B6 and A13A14B13B14" as shown in figure:

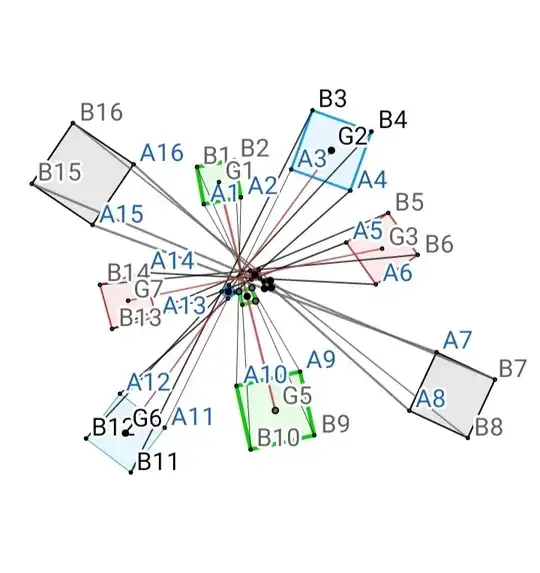

Step 05: Now again take "midpoint of Square A7A8B7B8 and A15A16B15B16" as shown in figure:

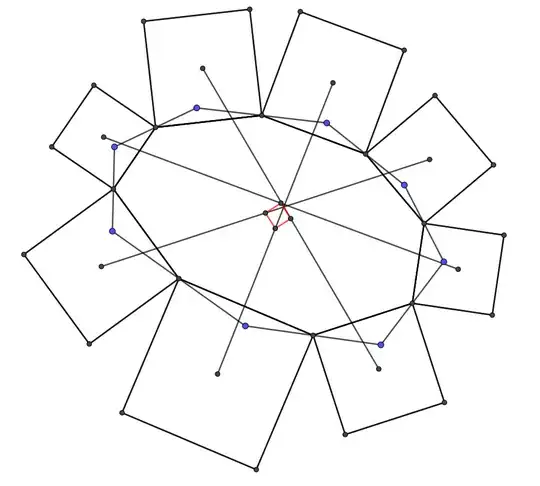

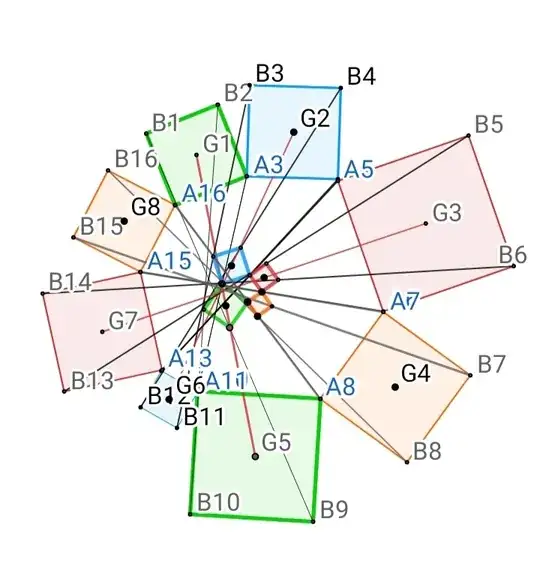

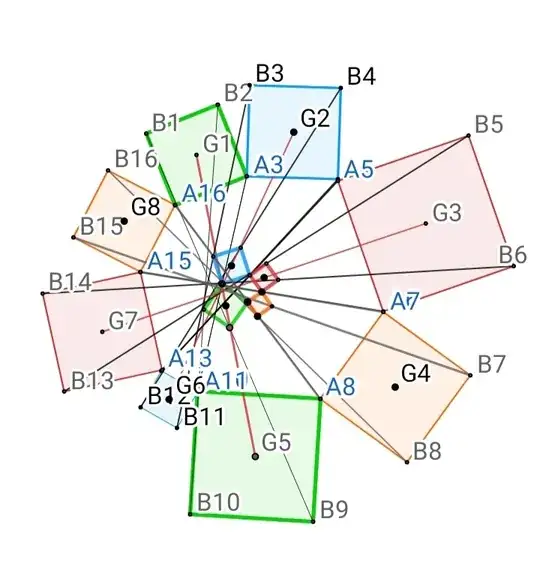

Step 06: When points A2=A3; A4=A5; A6=A7; A8=A9 ; A10=A11 ; A12=A13 ; A14=A15 ; A16=A1 then Figure will looks like this:

Conclusion 01: in steps 01 , we have shown that m(G1,G5) will be center of small green Square and Similarly if we take {G2,G3,....,G8) as center of Squares made on Base {A3A4; A5A6; ......; A15A16} then m(G2,G6);m(G3,G7) ;m(G4,G8) will be center of Squares made in step 03,04,05 and from Van Abuel's Theorem we will understand why those two lines are perpendicular to each other.

Conclusion 02: Proposition 10 is Special case of proposition 09 but question may arise why it becomes a Square?

Solution: The reason is very simple as "*It is well known fact that Centroid of Square made on sides of parallegram in same sence will makes another Square " which is mentioned as Napoleon Barlotti theorem in case of Quadrilateral".

Here is Hint about Where is Parallegram,

Hint= Let A1A2....A8 be convex irregular octagon and Let {C1,C2,....,C8} be m(A1, A2); m(A2,A3); ........; m(A8,A1) then you will find that m(C1,C5) ; m(C2,C6); m(C3,C7);m(C4,C8) makes parallegram as Shown in this figure:

So from there you Can construct Square on C1C2, C2C3,...,C8C1 and Simillarly Apply all those Steps mentioned above , then you will find that Proposition 10 equivalent to Square mades on Sides of Parallegram!!.