Given a polynomial with real coefficients is there a method (e.g. from algebra or complex analysis) to calculate the number of complex zeros with a specified real part?

Background. This question is motivated by my tests related to this problem.

Let $p>3$ be a prime number. Let $G_p(x)=(x+1)^p-x^p-1$, and let $$F_p(x)=\frac{(x+1)^p-x^p-1}{px(x+1)(x^2+x+1)^{n_p}}$$ where the exponent $n_p$ is equal to $1$ (resp. $2$) when $p\equiv-1\pmod 6$ (resp. $p\equiv1\pmod 6$).

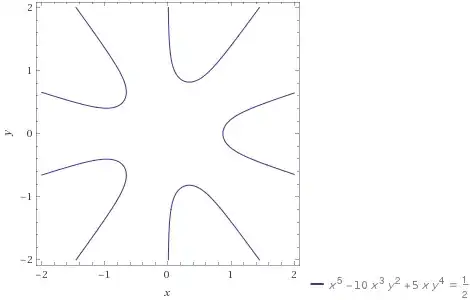

The answer by Lord Shark the Unknown (loc. linked) implies that $F_p(x)$ is a monic polynomial with integer coefficients. The degree of $F_p$ is equal to $6\lfloor(p-3)/6\rfloor$. I can show that the complex zeros of $F_p(x)$ come in groups of six. Each of the form $\alpha,-\alpha-1,1/\alpha,-1/(\alpha+1),-\alpha/(\alpha+1),-(\alpha+1)/\alpha.$ That is, orbits of a familiar group (isomorphic to $S_3$) of fractional linear transformations.

My conjecture. Exactly one third of the zeros of $F_p(x)$ have real part equal to $-1/2$.

I tested this with Mathematica for a few of the smallest primes and it seems to hold. Also, each sextet of zeros of the above form seems to be stable under complex conjugation, and seems to contain a complex conjugate pair of numbers with real part $=-1/2$. Anyway, I am curious about the number of zeros $z=s+it$ of the polynomial $F_p(x)$ on the line $s=-1/2$.

Summary and thoughts.

- Any general method or formula is welcome, but I will be extra grateful if you want to test a method on the polynomial $G_p(x)$ or $F_p(x)$ :-)

- My first idea was to try the following: Given a polynomial $P(x)=\prod_i(x-z_i)$ is there a way of getting $R(x):=\prod_i(x-z_i-\overline{z_i})$? If this can be done, then we get the answer by calculating the multiplicity of $-1$ as a zero of $R(x)$.

- May be a method for calculating the number of real zeros can be used with suitable substitution that maps the real axes to the line $s=-1/2$ (need to check on this)?

- Of course, if you can prove that $F_p(x)$ is irreducible it is better that you post the answer to the linked question. The previous bounty expired, but that can be fixed.

May be a method for calculating the number of real zeros can be usedLet $,x=-1/2 + i z,$, then $,P(x)=A(z) + i B(z),$ with $,A,B \in \mathbb{R}[\text{x}],$ has roots with real part $,-1/2,$ iff $,\gcd(A,B),$ has real roots. The computations would not be pretty, though. – dxiv Jul 17 '18 at 20:55