It's well known that 3 random variables may be pairwise statistically independent but not mutually independent, for an illustration see: example pairwise vs. mutual relations.

Can mutual statistical independence be modeled with Bayesian Networks aka Graphical Models? These are nonparametric structured stochastic models encoded by Directed Acyclic Graphs.

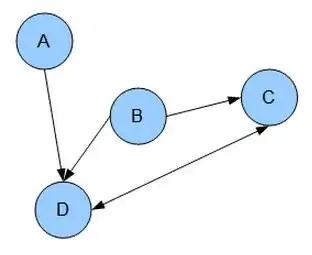

"Each vertex represents a random variable (or group of random variables), and the links express probabilistic relationships between these variables. The graph then captures the way in which the joint distribution over all of the random variables can be decomposed into a product of factors each depending only on a subset of the variables." -- CM Bishop Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning, Ch. 8 p. 630.

Here's a basic example from Wikipedia:

It would appear that hypergraphs are needed to represent the higher order (in)dependence. Is there some trick based on "d-separation", "Markov Blankets" or maybe grouping variables that would enable such a representation?