Please refresh the page at least once for the hyperlinks to work properly.

$\require{begingroup}\begingroup\renewcommand{\dd}[1]{\,\mathrm{d}#1}$This is the second half of the tentative solution, following the first half. The whole attempt is too long (over the input limit of $30$k characters) for a single post.

Sec.3.1$\quad$ Encoding going from $n = 3$ to $n = 5$

Here's the formal statement the rules (algorithm) for generating the codes (configurations) for $n+1$ given those of $n$. Each rule is considered proven, as they are obviously true by demonstration.

- The new point (the $(n+1)$th point) can go only after the $n$th point, by construct.

- There's no variation in the "all-negative" piece. Just attach the new point at the end.

- The new point can go between $0$ and any of the "gaps" symbolized by $C_X,D_X,E_X,\ldots$ etc that are explicitly present in the code (not out of bounds).

- The inadmissible region $P_X$ for any point $P$ is attached to the end of the code if and only if $P$ is in front of zero. In other words, $P_{t}$ and $P_t$ are out of bounds ("more negative" than $\theta = -t$) if and only if $P$ comes after zero.

Going to $\mathbf{n = 4}$ by inserting $D$. We get three pieces of $n = 4$ from the baseline piece of $n = 3$, and there's only one descendant from the all-negative piece:

$$\begin{array}{c|cccccc|c}

\mathbf{ \Gamma(1) } & C & & 0 & & C_X & & \\ \hline

\Gamma(1, \frac13) & C & D & 0 & & C_X & D_X & \scriptsize \text{new baseline for}~ n=4 \\

\Gamma(1, \frac23) & C & & 0 & D & C_X & & \\

\Gamma(1, \frac33) & C & & 0 & & C_X & D & \\

\end{array} \\

\begin{array}{c|ccc|c}

\mathbf{ \Gamma(-1) } & 0 & C & & \\ \hline

\Gamma(-1, -1) & 0 & C & D & \scriptsize \text{new all-negative for}~ n=4

\end{array}$$

Reminder: the gaps $C_X$ and $D_X$ are out of bounds (more negative than $A_{-t}$ at $\theta = -t$ ). It is indeed true that these inadmissible range like $D_X$ can be in the upper half ($0 < \theta < t < \frac12$). No worries, the ranges for points (integration limits) will work out "automatically", necessarily leading to a sequence of decreasing spaces that yields the simplex volume.

#####Going to $\mathbf{n = 5}$, we have the $2^{n-2} = \text{four}$ configurations from $n = 4$ that makes up \ref{Eq_f4} encoded as $\Gamma(1,\frac13), \Gamma(1,\frac23), \Gamma(1,\frac33)$, and $\Gamma(-1,-1)$ just above.

Let’s start with the baseline, inserting the fifth point $E$ yields four new configurations.

$$\begin{array}{c|ccccccccc|c}

\mathbf{ \Gamma(1, \frac13) }& C & D & & 0 & & C_X & & D_X & & \\ \hline

\Gamma(1, \frac13, \frac14) & C & D & E & 0 & & C_X & & D_X & E_X & \scriptsize \text{new baseline for}~ n=5 \\

\Gamma(1, \frac13, \frac24) & C & D & & 0 & E & C_X & & D_X & & \\

\Gamma(1, \frac13, \frac34) & C & D & & 0 & & C_X & E & D_X & & \\

\Gamma(1, \frac13, \frac44) & C & D & & 0 & & C_X & & D_X & E &

\end{array}$$

The remaining two of the "bloodline of $n = 4$ baseline" $\Gamma(1, \cdot)$ produce two and one respectively:

$$\begin{array}{c|cccccc}

\mathbf{ \Gamma(1, \frac23) } & C & 0 & D & & C_X & \\ \hline

\Gamma(1, \frac23, \frac12) & C & 0 & D & E & C_X & \\

\Gamma(1, \frac23, \frac22) & C & 0 & D & & C_X & E \\

\end{array} \quad,\quad \begin{array}{c|ccccc}

\mathbf{ \Gamma(1, \frac33) } & C & 0 & C_X & D & \\ \hline

\Gamma(1, \frac33, 1) & C & 0 & C_X & D & E

\end{array}$$

Of course, the all-negative for $n = 4$ necessarily produces only the new all-negative.

$$\begin{array}{c|cccc|c}

\mathbf{ \Gamma(-1, -1) } & 0 & C & D & & \\ \hline

\Gamma(-1, -1, -1) & 0 & C & D & E & \scriptsize \text{all-negative for}~ n=5

\end{array}$$

These are the $(4+2+1)+1 = 2^{n-2} = \text{eight}$ configurations that have a one-to-one mapping with the constituent "pieces" of $~f_5(t)$, the \ref{Eq_f5} in Sec.1.

Sec.3.2$\quad$ Going to $n=6$ and Comments on $\Gamma$ Indexing and Lengths

Pardon me for not reproducing a table listing all the eight configs of $n = 5$ to save space.

Again, with the baseline of $n = 5$, one can see why it yields five configs for $n = 6$.

$$\begin{array}{c|cccccccccccc|c}

\mathbf{ \Gamma(1, \frac13, \frac14) } & C & D & E & & 0 & & C_X & & D_X & & E_X & & \\ \hline

\Gamma(1, \frac13, \frac14, \frac15) & C & D & E & F & 0 & & C_X & & D_X & & E_X & F_X & \scriptsize \text{baseline}~n=6 \\

\Gamma(1, \frac13, \frac14, \frac25) & C & D & E & & 0 & F & C_X & & D_X & & E_X & & \\

\Gamma(1, \frac13, \frac14, \frac35) & C & D & E & & 0 & & C_X & F & D_X & & E_X & & \\

\Gamma(1, \frac13, \frac14, \frac45) & C & D & E & & 0 & & C_X & & D_X & F & E_X & & \\

\Gamma(1, \frac13, \frac14, \frac55) & C & D & E & & 0 & & C_X & & D_X & & E_X & F &

\end{array}$$

The astute readers might already know that the remaining "base-bloodline" configs $\Gamma(1, \frac13,\cdot)$ will produce three, two, and one, respectively.

$$\begin{array}{c|ccccccccc}

\mathbf{\Gamma(1, \frac13, \frac24) } & C & D & 0 & E & & C_X & & D_X & \\ \hline

\Gamma(1, \frac13, \frac24, \frac13) & C & D & 0 & E & F & C_X & & D_X & \\

\Gamma(1, \frac13, \frac24, \frac23) & C & D & 0 & E & & C_X & F & D_X & \\

\Gamma(1, \frac13, \frac24, \frac33) & C & D & 0 & E & & C_X & & D_X & F \end{array} \\

\scriptsize\begin{array}{c|ccccccc}

\mathbf{\Gamma(1, \frac13, \frac34) } & C & D & 0 & C_X & E & & D_X & \\ \hline

\Gamma(1, \frac13, \frac34, \frac12) & C & D & 0 & C_X & E & F & D_X & \\

\Gamma(1, \frac13, \frac34, \frac22) & C & D & 0 & C_X & E & & D_X & F

\end{array} \quad \begin{array}{c|ccccccc}

\mathbf{\Gamma(1, \frac13, \frac44) } & C & D & 0 & C_X & D_X & E & \\ \hline

\Gamma(1, \frac13, \frac44, \frac11) & C & D & 0 & C_X & D_X & E & F

\end{array}$$

Continue the descending pattern, the "secondary base-bloodline" $\Gamma(1, \frac23,\cdot)$ render two and one. Then there's the "single bloodline".

$$\begin{array}{c|ccccccc}

\mathbf{\Gamma(1, \frac23, \frac12) } & C & 0 & D & E & & C_X & \\ \hline

\Gamma(1, \frac23, \frac12, \frac12) & C & 0 & D & E & F & C_X & \\

\Gamma(1, \frac23, \frac12, \frac22) & C & 0 & D & E & & C_X & F \end{array} \quad

\begin{array}{c|cccccc}

\mathbf{\Gamma(1, \frac23, \frac22) } & C & 0 & D & C_X & E & \\ \hline

\Gamma(1, \frac13, \frac34, \frac22, 1) & C & 0 & D & C_X & E & F \end{array} \\

\begin{array}{c|cccccc}

\mathbf{\Gamma(1, \frac33, 1) } & C & 0 & C_X & D & E & \\ \hline

\Gamma(1, \frac13, \frac33, 1, 1) & C & 0 & C_X & D & E & F

\end{array}$$

Lastly the all-negative:

$$\begin{array}{c|ccccc|c}

\mathbf{\Gamma(-1, -1, -1) } & 0 & C & D & E & & \\ \hline

\Gamma(-1, -1, -1, -1) & 0 & C & D & E & F & \scriptsize \text{all-negative for}~ n = 6

\end{array}$$

These are the $(5 + 3 + 2 + 1) + (2+1) + 1 + 1 = 2^{n-2} = 16$ pieces mapping to $~f_6(t)$, the Eq.(6) in Sec.1.

Some comments on the $\Gamma$ indexing:

- Baseline pieces have ascending consecutive denominators and $1$ in the numerator: $\Gamma(1, \frac13), \Gamma(1, \frac13, \frac14), \Gamma(1, \frac13, \frac14, \frac15),\ldots$

- An argument of $\Gamma$ being $1$ means the bloodline becomes single line from there. The arguments in fractions like $\frac55, \frac44$ and $\frac22$ equal $1$ not by accident.

- The all-negative might as well all be denoted as just $\Gamma(-1)$

- There are $n - 2$ indices in $\Gamma(j,k,\ell,\ldots)$. That is, the number of arguments in $\Gamma$ indicates the number of points.

According to the rules for generating the codes (algorithm), it's easy to see the recurrence algorithm for the length (number of pieces) in each "bloodline":

- Each number gives a descending sequence of that length (e.g. whenever you see a $3$ it creates a $[3,2,1]~$).

- The very first (longest) sequence has the leading term bumped up by one (due to the special role of $0 = B_X$ in the code). For the first few $n$:

$$

[3,1] \\

[4, 2, 1], [1] \\

[5,3,2, \color{magenta}1], [2, \color{green}1], [1], [1] \\

[6,4,\underline{\mathbf{3}},2,\color{red}1], [3, 2, \color{blue}1], [2,1], \color{magenta}{[1]}, [2,\color{orange}1],\color{green}{[1]},[1],[1] \\

\scriptsize[7,5,4,3,2,1], [4, 3, 2, 1], \underline{\mathbf{[3,2,1]}}, [2,1], \color{red}{[1]},[3,2,1],[2,1], \color{blue}{[1]} ,[2,1],[1],\color{magenta}{[1]},[2,1], \color{orange}{[1]},\color{green}{ [1]},[1],[1]

$$

It's easy to prove this two-rule algorithm for the length at any $n$ leads to a total of $2^{n-2}$.

By design, given a legit $\Gamma$ that correctly corresponds to a code, one can reconstruct the code by reading the indices. For example, given $\Gamma(1,\frac13,\frac24,\frac23)$ one can deduce the code to be $\{C,D,0,E,C_X,F,D_X\}$ in the following manner.

- First index $1$ means $C$ is in front of zero, $\implies \{C,0,C_X\}$

- Second index $\frac13$ means $D$ goes in the first of the 3 spaces, $\{C, \_\_,0, \_\_,C_X,\_\_ \} \implies \{C,D,0,C_X,D_X \}~$, where $D_X$ is in the code (inside the bound, $d + t - 1 > -t~$) because $D$ is in front of zero.

- Third index $\frac24$ means $E$ goes to the 2nd of the 4 spaces that follow $D$, $\{C, D,\_\_,0, \_\_,C_X,\_\_,D_X,\_\_ \} \implies \{C,D,0,E,C_X,D_X \}~$, where $E_X$ is out of bounds because $E$ is behind $0$.

- Fourth index $\frac23$ means $F$ falls in the 2nd of the 3 spaces that follow $E$, $\{C, D,0, E,\_\_,C_X,\_\_,D_X,\_\_ \} \implies \{C,D,0,E,C_X,F,D_X \}~$, where again $F_X$ is not inside due to $f<0~$.

Conversely, one can deduce the $\Gamma$ indexing directly by reading the code, without needing to go through the hierarchical listing of all the levels below.

Sec.3.3$\quad$ Density Pieces from Encoded Configurations: the Simplex Volumes

The previous subsections established the natural codes (listing of configurations). Here we state the rules/algorithm to read the contribution to the density from a given code.

Denote the range of point $C$ (integration limit) as $\mathcal{R}_c = \mathcal{U}_c - \mathcal{L}_c$ the upper limit minus the lower limit, then:

- All configurations contribute to the density in the form of $\frac1{(n-2)!} \mathcal{R}_c^{n-2}~$, which is the volume of a simplex with side length $\mathcal{R}_c = t - (k_U+k_L)(1 - 2t)$, with $k_U$ and $k_L$ described below.

- The upper limit is always either $t$ or $3t-1$. Namely, $\mathcal{U}_c = t - k_U(1 - 2t)$ where $k_U = 0$ or $1$ is the number of group of points behind zero and in front of $C_X$.

- The lower limit is always in the form of $\mathcal{L}_c = k_L(2t-1)$ where $k_L$ counts the number of groups of points behind $C_X$. The gaps $D_X$ and $E_X$ act as dividers (bin edge), and points between the same pair of dividers are considered a single group.

The rules to count $k_U$ and $k_L$, are obviously true as demonstrated previously in Sec.2.2: the "one-gap-reduction" and "one-gap-lift" correspond to the two separate origins of the gap (same magnitude $1-2t$).

For example, at $n = 9$ with point $A$ to point $I$

- The configuration $\{C, D, 0, E, F, C_X, G, D_X, H, I \}$ which is indexed as $\Gamma(1,\frac13,\frac24,\frac13,\frac23,\frac23,1)$ contributes $\frac{(7t-3)^7}{7!}$ with an overall $9!$ in front, because there is one group $\{E, F\}$ in front of $C_X$ and two groups $\{G\}$ and $\{H, I\}$ behind $C_X$.

- The configuration $\{C, D, E, 0, C_X, F, G, D_X, E_X, H, I\}$ which is indexed as $\Gamma(1,\frac13,\frac14,\frac35,\frac13,\frac33,1)$ contributes $9!\,\frac{(5t-2)^7}{7!}$, because there is zero group in front of $C_X$ and two groups $\{F,G\}$ and $\{H, I\}$ behind $C_X$. Note that $E_X$ immediately follows $D_X$ and has no effect.

- The new and "last" piece is the configuration $\{C, D, E, 0, F, C_X, G, D_X, H, E_X, I \}$ which index is $\Gamma(1,\frac13,\frac14,\frac25,\frac24,\frac23,\frac22)$. The density from this config is $72(9t-4)^7$, because there is one group $\{F\}$ in front and three groups $\{F\}$, $\{G\}$, and $\{I\}$ after $C_X$.

Here's another quick look at where the circular diagram is clearly helpless. At $n = 16$ with points $A$ to $P$, the configuration

$$\begin{aligned}

&\Gamma(1,\frac13,\frac14,\frac15,\frac26,\frac15,\frac14,\frac13,\frac12,\frac12,\frac12,\frac22,1,1) \\

&= \{C, D, E, F, 0, G, H, C_X, I, D_X, J, E_X, K, L, M, F_X, N, O, P\}\end{aligned}$$

corresponds to a piece of $16!\,\frac{(11t-5)^{14}}{14!}$ where the total of $k_U + k_L = 1+4=\text{five}$ groups are $\{G,H\}$, $\{I\}$, $\{J\}$, $\{K,L,M\}$, and $\{N,O,P\}$. For the record, we know that for $n = 16$ the highest order is $(15t-7)^{14}$, see \ref{Eq_fn}. This is achieved by configurations such as

$$\begin{aligned}

& & &\{C, \ldots, H, 0, I, C_X, J, D_X, K, E_X, L, F_X, M, G_X, N, H_X, O, P\} \\

&\text{and} & &\{C, \ldots, I, 0, J, C_X, K, D_X, L, E_X, M, F_X, N, G_X, O, H_X, P, I_X\}~,\end{aligned}$$

among the ${n-1 \choose k}=15$ where $k \lfloor \frac{n-1}2\rfloor = 7$.

The proof about the simplex volume can perhaps be done with induction, while intuitively it's at least reasonable in that one can see the points having hierarchically restricted space.

Concluding Remarks

Many details of different levels can be formalized into rigorous proofs, but to be honest the effort I've made so far is not enough to overcome the majority of the technicalities.

Several less trivial claims are stated as "obviously true by demonstration", in the sense that: the process of using the circular diagram and encoding the configurations has been enough to convince the author that the results are true. The geometric and combinatorial nature of the problem is manifested by the construct.

Roughly speaking, the "solution" goes like

- Establishing the encoding as an exact representation of the problem.

- Showing via the codes that there are $2^{n-2}$ disjoint configurations.

- Showing via the codes that each configuration contributes to a simplex volume.

- Showing that this holds for all $n \geq 3$.

Arguably, not displaying a proof for (2) here in the post isn't a big deal. As for (4) the recurrence, it's a judgement call whether one can take it as true, perhaps having some faith in the induction proof (which formulation is hinted by the demonstration).

The most important task to continue is to fix the lack of semi-rigorous derivation for (3): the simplex volume, either for a given $n$, or with induction from trivial cases $n = 2$ and $3$.$\endgroup$

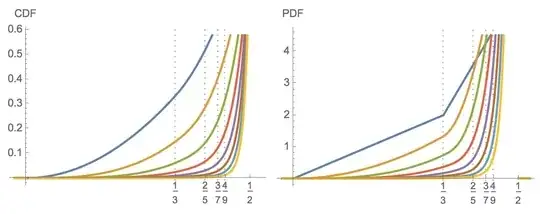

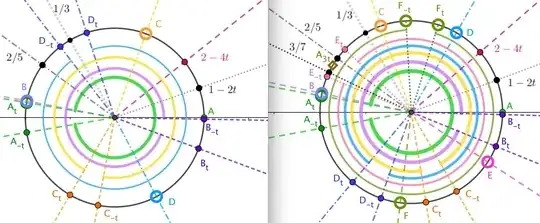

The plots above show left the CDF and right the density:

The plots above show left the CDF and right the density:  For the following bullets, figures that come later might be more suitable than the two above.

For the following bullets, figures that come later might be more suitable than the two above.

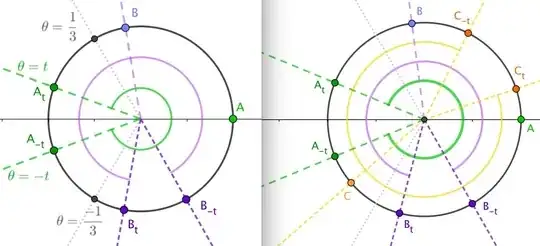

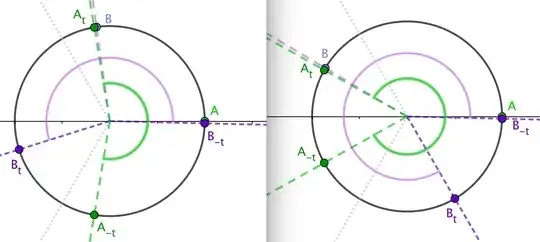

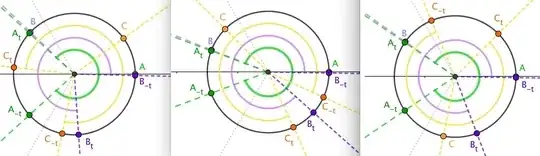

The one-gap-reduction of upper limit of

The one-gap-reduction of upper limit of