In a previous post I asked help to clarify a property of stable convergence in distribution:

Definition

Let $X_n$ be a sequence of random variables defined on a probability space $(\Omega,\mathcal{F},\mathbb{P})$ with value in $\mathbb{R}^N$. We say that the sequence $X_n$ converges stably in distribution with limit $X$, written $X_n\stackrel{\text{st}}{\longrightarrow} X$, if and only if, for any bounded continuous function $f:\mathbb{R}^N\to\mathbb{R}$ and for any $\mathcal{F}$-measurable bounded random variable $W$, it happens that: $$ \lim_{n\rightarrow \infty}\mathbb{E}[f(X_n)\,W]=\mathbb{E}[f(X)\,W]. $$

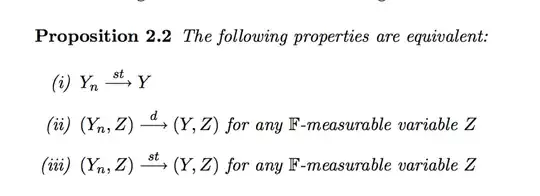

What I need to prove now is the following:

Assume $$ (Y_n,Z)\stackrel{\text{d}}{\longrightarrow}(Y,Z), $$

for all measurable random variable $Z$, then

$$ (Y_n,Z)\stackrel{\text{st}}{\longrightarrow}(Y,Z) $$ for all measurable random variables $Z$. So I need to prove that, for any bounded continuous function $f$ and for any measurable $Z$ it holds that $$ \lim_{n\rightarrow \infty}\mathbb{E}[f(Y_n,Z)\,W]=\mathbb{E}[f(Y,Z)\,W] $$ for all bounded random variables $W$.

I tried unsuccessfully with Portmanteau and Levy continuity theorem…

=================================================================

In practice I am trying to prove this proposition from the paper by Podolskij and Vetter:

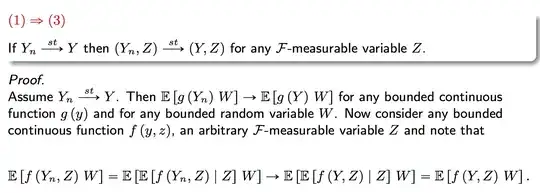

I did this reasoning for (1)=>(3), but I am not so sure of its correctness.