Both methods are related to the binary representation of the exponent.

The ideas that tie all these things together is that every time you go one place to the left in a binary number, you multiply the number by two;

and when you square a number, you multiply its exponent by two.

The method given by Khan Academy is what I would have thought of as "repeated squaring." From the binary representation,

$\newcommand{two}{\mathrm{two}} 383_\mathrm{ten} = 101111111_\two,$

we determine that we need nine binary digits.

The leftmost digit is the digit for $2^8 = 256.$

We therefore write our first power and then start squaring:

\begin{align}

3^1 &\equiv 3 \pmod7 && \text{(first power)}\\

3^2 &\equiv 2 \pmod7 && \text{(previous number squared)} \\

3^4 &\equiv 4 \pmod7 && \text{(squared again)} \\

3^8 &\equiv 2 \pmod7 && \text{(squared again)} \\

3^{16} &\equiv 4 \pmod7 && \text{(notice the pattern?)} \\

3^{32} &\equiv 2 \pmod7 \\

3^{64} &\equiv 4 \pmod7 \\

3^{128} &\equiv 2 \pmod7 \\

3^{256} &\equiv 4 \pmod7

\end{align}

This becomes repetitive (and therefore easy) very quickly in this case:

$2^2 \equiv 4 \pmod7$ and $4^2 \equiv 2 \pmod7,$

so it's just alternating $2$s and $4$s after the first few lines.

Next, we multiply together the powers that correspond to the binary digits we need:

\begin{align}

100000000_\two &= 256 &

3^{256} &\equiv 4 \pmod7 \\

101000000_\two &= 256 + 64 = 320 &

3^{320} \equiv 4 \times 3^{64} \equiv 4\times 4 &\equiv 2 \pmod7 \\

101100000_\two &= 320 + 32 = 352 &

3^{352} \equiv 2 \times 3^{32} \equiv 2\times 2 &\equiv 4 \pmod7 \\

101110000_\two &= 352 + 16 = 368 &

3^{368} \equiv 4 \times 3^{16} \equiv 4\times 4 &\equiv 2 \pmod7 \\

101111000_\two &= 368 + 8 = 376 &

3^{376} \equiv 2 \times 3^8 \equiv 2\times 2 &\equiv 4 \pmod7 \\

101111100_\two &= 376 + 4 = 380 &

3^{380} \equiv 4 \times 3^4 \equiv 4\times 4 &\equiv 2 \pmod7 \\

101111110_\two &= 380 + 2 = 382 &

3^{382} \equiv 2 \times 3^2 \equiv 2\times 2 &\equiv 4 \pmod7 \\

101111101_\two &= 382 + 1 = 383 &

3^{383} \equiv 4 \times 3^1 &\equiv 5 \pmod7

\end{align}

In practice, of course, we only need to write the rightmost equivalences

on each line. The rest of it is just to show why it works.

Basically, the idea is that you can get the exponent $101111101_\two = 383$

by taking the sum

\begin{multline}

100000000_\two + 1000000_\two + 100000_\two + 10000_\two \\+ 1000_\two + 1000_\two + 100_\two + 10_\two + 1_\two.

\end{multline}

We construct the power of $3$ by multiplying the powers corresponding to the

addends in this sum.

Note that you could multiply powers starting with the highest power (as shown above) or starting with the lowest power.

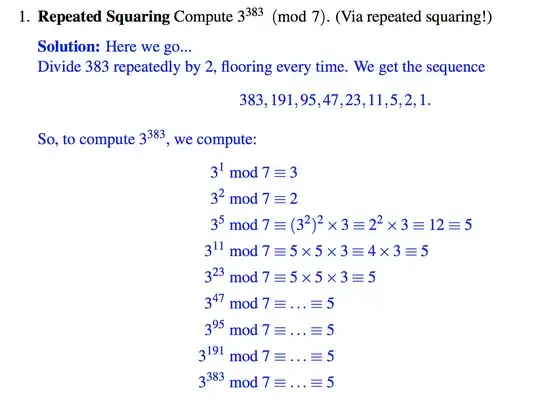

But where the Khan Academy method simply adds the various powers of $2$

to get the exponent, the method given in your text corresponds to a

"shift left and add" method of building the exponent.

That is, we start with the leading bit of the binary exponent,

but we put it in the one's place. We then repeatedly multiply by $2$

(which "shifts" all the binary digits one place to the left)

and (when needed) add $1$ to write another digit of the number,

working from left to right.

Doubling the exponent corresponds to squaring the power of $3$

and adding $1$ corresponds to multiplying by $3$:

\begin{align}

1_\two &= 1 & 3^1 &\equiv 3 \pmod7 \\

10_\two &= 2 \times 1 = 2 & 3^2 &\equiv 2 \pmod7 \\

101_\two &= 2 \times 2 + 1 = 5 &

3^5 \equiv (3^2)^2 \times 3 \equiv 4 \times 3 &\equiv 5 \pmod7 \\

1011_\two &= 2 \times 5 + 1 = 11 &

3^{11} \equiv (3^5)^2 \times 3 \equiv 4 \times 3 &\equiv 5 \pmod7 \\

10111_\two &= 2 \times 11 + 1 = 23 &

3^{23} \equiv (3^{11})^2 \times 3 \equiv 4 \times 3 &\equiv 5 \pmod7 \\

101111_\two &= 2 \times 23 + 1 = 47 &

3^{47} \equiv (3^{23})^2 \times 3 \equiv 4 \times 3 &\equiv 5 \pmod7 \\

1011111_\two &= 2 \times 47 + 1 = 95 &

3^{95} \equiv (3^{47})^2 \times 3 \equiv 4 \times 3 &\equiv 5 \pmod7 \\

10111111_\two &= 2 \times 95 + 1 = 191 &

3^{191} \equiv (3^{95})^2 \times 3 \equiv 4 \times 3 &\equiv 5 \pmod7 \\

101111111_\two &= 2 \times 191 + 1 = 383 &

3^{383} \equiv (3^{191})^2 \times 3 \equiv 4 \times 3 &\equiv 5 \pmod7

\end{align}

As long as we do not make any arithmetic errors, we inevitably get the same result on the left as when we do it the other way,

therefore we get the same result on the right as well.