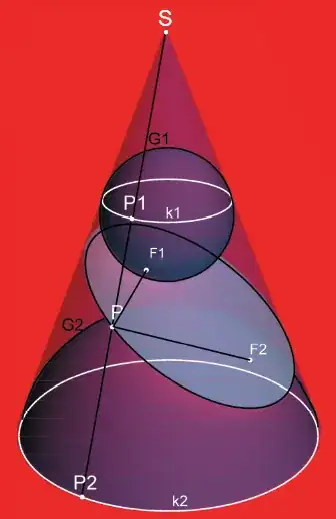

I will attempt to give an intuitive argument why it is possible for the intersection of the plane and cone to be an ellipse.

This may make it easier to accept the more rigorous mathematical arguments that show that the intersection must be an ellipse.

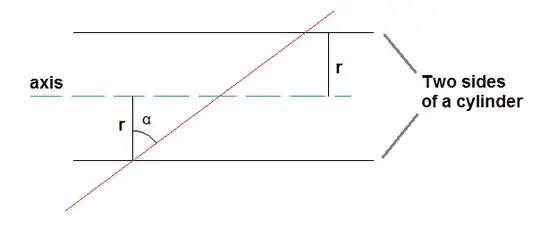

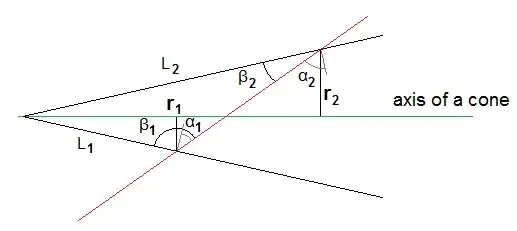

Suppose we are given a cone and a slant surface that cuts completely across the cone. Consider the many circular sections of the cone perpendicular to its axis, and the intersection of each of these circular disks with the slant surface.

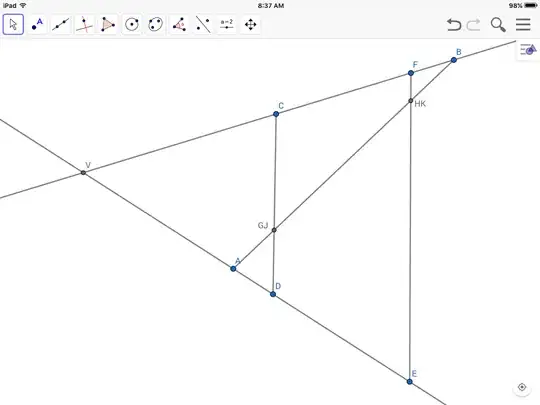

Of all of these disks, the one closest to the cone's vertex intersects the

slant plane at only one point. Let's call that point $P.$

The disk farthest from the cone's vertex also intersects the

slant plane at only one point. Let's call that point $Q.$

The intersections of the other disks with the slant plane are line segments, and all parallel to each other and perpendicular to the line segment $PQ.$ These parallel segments can be viewed as chords or "widths" of the conic section formed by intersection of the cone and the slant plane, measured at different positions along $PQ.$

For disks very near the points $P$ or $Q,$ these line segments are short.

The largest such line segment is not between point $P$ and the axis,

because as we on the slant plane from $P$ toward the axis, we are both getting closer to the axis (which would tend to increase the length of the intersection segment even if we were intersecting a cylinder instead of a cone), but we are also intersecting larger disks, which also tends to make the intersection lines longer.

Now consider the disk that intersects the axis of the cone at the same point where the slant plane intersects the axis. As the slant plane passes through this disk, the distance from the axis is having almost no effect on the length of the intersection segments (because when you take chords near the diameter of a circle, the change in the length of the chord is much, much less than the distance between the chord and the diameter),

but the slant plane is still cutting into larger and larger disks,

so the length of the intersection segments keeps increasing due to that effect.

Eventually, of course, the effect of moving away from the axis

(cutting through smaller parts of the disk) will overcome the effect of cutting larger and larger disks, because eventually the intersection shrinks down to a point at $Q.$ So the largest intersection segment is somewhere between the axis and $Q.$

But as you will notice from a momentary examination of a cross-section of the cone along the axis, showing how the slant plane intersects the cone at points $P$ and $Q,$ the point $P$ is closer to the vertex than $Q$ is, and therefore also closer to the axis. So the midpoint of $PQ$ is somewhere between the axis and $Q.$

Now we have that the largest chord ("width") of the conic section occurs not on the axis of the cone, but somewhere between the axis and the point $Q$; and also the midpoint of $PQ$ is somewhere between the axis and the point $Q.$

It turns out these two things are in fact exactly the same distance from the axis of the cone, that is, the longest chord of the conic section passes through the midpoint of the axis $PQ$ of the conic section.

This argument has not demonstrated that fact, of course; that is what the more rigorous mathematical proofs are for.

But this argument should make it a little more palatable that both of these things can occur at the same place.