Every theory has axioms, which are some propositions held to be true without being proven from anything else, and are not provable from each other. Subsequent truths of the theory derived from the axioms are theorems.

The properly termed question is whether the empty set being a subset of every other set is axiom of set theory, or a theorem.

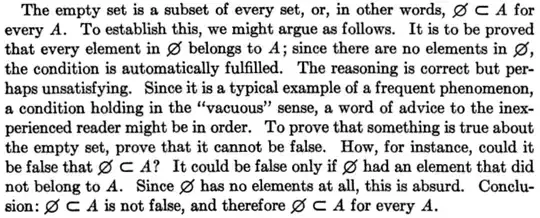

It depends on how "subset" is defined. If $A\subset B$ means that every element of $A$ is in $B$, it is not necessarily true that $\emptyset$ is a subset of anything, since it has no elements. In this case, $\emptyset \subset A$ can be added as an axiom. It doesn't conflict with anything, and simplifies all reasoning about subsets. Alternatively, if $A\subset B$ is defined as "$A$ has no elements that are not also in $B$", then we do not require the extra axiom for the $\emptyset$ case. If $A$ has no elements at all, it has no elements that are not in $B$.

Suppose that we use the first, positively termed definition of subset, and then adopt as an axiom not $\forall A:\emptyset \subset A$, but rather its negation: $\exists A:\emptyset \not\subset A$, or the outright proposition $

\forall A:\emptyset \not\subset A$.

This is just going to cause problems. We can "do" set theory as before, but all the theorems will be uglified by having to avoid the special cases involving the empty set. In any derivation step in which we rely on a subset relation being true, or assert one, we will have to add the verbiage of an additional statement which asserts that the variable in question doesn't denote the empty set. This proposition then has to be carried in all the remaining derivations, unless something else makes it superfluous (some unrelated assurance from elsewhere that the set in question isn't empty).

Working with this clumsy subset definition that doesn't work with the empty set very well, someone is eventually going to have an epiphany and introduce a new subset-like relation which doesn't have these ugly problems: a new $A\ \mathbf{subset*}\ B$ binary relation which reduces exactly to $A\subset B$ when neither $A$ nor $B$ are $\emptyset$, and which, simply by definition, reduces to a truth whenever $A = \emptyset$, regardless of $B$. That person will then realize that all the existing work is simpler if this $\mathbf{subset*}$ operation is used in place of $\subset$.

At the end of the day it boils down to criteria like: is the system consistent (doesn't contradict itself), is it complete (does it capture the truths we want) and also is it convenient: are the rules configured so that we do not trip over unnecessary cases and superfluous logic.