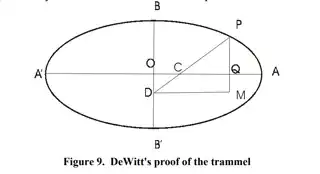

Here's a diagram of the device I mean, hard at work drawing an ellipse. I find this quite surprising, and would like to get to the bottom of things.

Essentially, a rod (black line in animation) is anchored to two sliders (in blue): One at an end, the other somewhere in the middle. The non-anchored end (black square) can move freely, tracing an ellipse, as the sliders move along perpendicular axes -- the end anchor along the minor axis, the interior anchor the major axis.

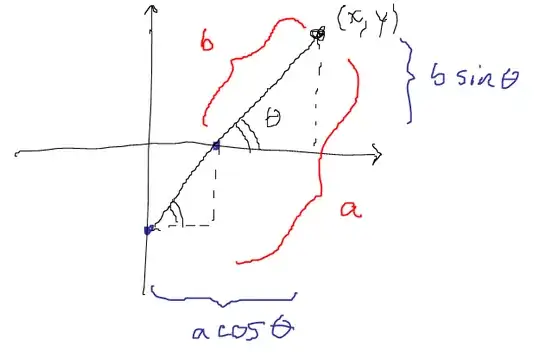

If you're willing to set up shop and start giving coordinates to the end that draws the ellipse (letting $a$ be the length of the rod, $b$ the distance from interior anchor to free end), it's not too hard to see that

\begin{align*} x &= a \cos \theta \\ y &= b\sin \theta, \end{align*}

and so in turn $$\frac{x^2}{a^2} + \frac{y^2}{b^2} = 1,$$

verifying the motion is indeed elliptical.

But I find this pretty unsatisfactory; until introducing coordinates, I had no reason to believe that an ellipse should be created. Even having introduced coordinates and verifying, I still find it very mysterious. What property of an ellipse am I missing that makes this device "obviously" draw an ellipse?

To put it another way: How could someone knowing only classical geometry (i.e., someone without coordinate geometry) have designed this machine to draw an ellipse? I am assuming that, being named after Archimedes, the device at least predates Descartes and thus coordinate geometry. Although, the runners do form something of a coordinate axis...

Compare this mysterious motion with the much more widely known method of putting pushpins down and tying one end of a string to each, pulling the string taut. This method is more apparent in how it generates an ellipse: the string has a fixed length which is the sum of distances from the pencil to each pushpin. This obeys the key and classically-known property that the sum of distances from foci to a point on the ellipse is a fixed distance.

![By Alastair Rae (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) or GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html)], via Wikimedia Commons](../../images/d4443645cdabf9c9e0e814b83d8595dc.webp)