Why are only two tangents possible to a hyperbola from a point? If we treat the hyperbola as two individual parabolas, then a point should be able to create two tangents through it for both of them, hence a total of 4.

-

5But a hyperbola doesn't consist of two parabolas. – Wojowu May 13 '16 at 07:11

-

2The fact that a hyperbola has asymptotes (and a parabola does not) is significant here. – Blue May 13 '16 at 07:11

-

Just by imagining a point between the two vertices of the hyperbola, mentally 4 tangents can be imagined. Normally, we have trouble imagining things that math says exists but here it's the other way around rather. If anyone could mathematically explain why only two are possible, it'd be great. – Shreyash Chaudhari May 13 '16 at 07:13

-

If your hyperbola has the form $y=1/x$ then you might imagine that of the four intuitive potential tangents from a particular point to the hyperbola, two might have negative gradients and two positive gradients. But in fact all tangents of this hyperbola have negative gradient $\frac{dy}{dx}=-1/{x^2}$, so you can immediately eliminate the other two. – Henry May 13 '16 at 09:47

2 Answers

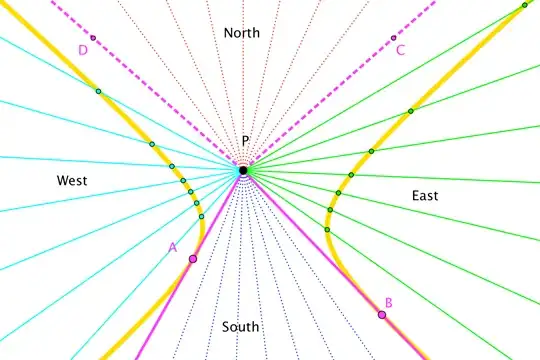

The diagram shows a point $P$ between the arms of a hyperbola. It also shows how the rays emanating from $P$ fall into four regions (denoted "North", "South", "East", "West") bounded by $\overrightarrow{PA}$, $\overrightarrow{PB}$, $\overrightarrow{PC}$, $\overrightarrow{PD}$:

Rays in the North and South regions never hit the hyperbola at all. Rays in the East and West regions cut the hyperbola.

The boundary rays are special.

$\overrightarrow{PA}$ and $\overrightarrow{PB}$ are tangent to the hyperbola (at "finite" points).

$\overrightarrow{PC}$ and $\overrightarrow{PD}$ are parallel to the (invisible) asymptotes of the hyperbola. (It's often helpful to think of these as being tangent to the hyperbola at the "point at infinity", but that's not the sense in which you're using tangency.)

(It's also good to know that the ray opposite $\overrightarrow{PC}$ separates the "Western" rays into two sub-regions: those that meet the hyperbola once, and those that meet it twice; likewise, the ray opposite $\overrightarrow{PD}$ sub-divides the "Eastern" rays.)

Moving $P$ can alter the nature of the boundaries a bit; for instance, if $P$ lies directly between the vertices (but, say, "west" of center), then $\overrightarrow{PA}$ and $\overrightarrow{PD}$ become the tangents, while $\overrightarrow{PB}$ and $\overrightarrow{PC}$ are asymptote-parallels. But the overall idea holds here, and apart from the case in which $P$ coincides with the hyperbola's center, there are always two tangents and two asymptote-parallels.

Anyway, the fact that a hyperbola has asymptotes (and thus region-bounding rays parallel to those asymptotes) distinguishes the geometry here from that of "two parabolas", which would have no asymptotes (and thus no corresponding region-bounding rays).

- 83,939

-

2

-

-

-

As I am a newcomer to GeoGebra, I didn't know that such things were possible with it... May I ask you the "item" permitting to draw such pencils ? – Jean Marie May 13 '16 at 09:34

-

@JeanMarie: The "item" is fakery. :) For reasonably-uniform (and automatically-adjusting) separation of the rays, I used the Angle Bisector tool to divide $\angle APB$, and then sub-divide the halves, and then sub-divide the quarters; likewise for the other "regions". I drew a circle about $P$, marked the points where the angle bisectors met that circle, and then drew all the rays from $P$ through those points. Then I hid all those bisectors, the circle, and the points, leaving only the rays. Easy! ;) – Blue May 13 '16 at 09:41

-

Thanks ! I think that I have to spend some more hours on this software in order that this kind of ideas come naturally to my mind. When one is accustomed to a powerful language as Matlab; the trend is to try to use it whatever the situation at hand (as you can see in my solution) whereas, sometimes, one should look elsewhere... – Jean Marie May 13 '16 at 09:55

-

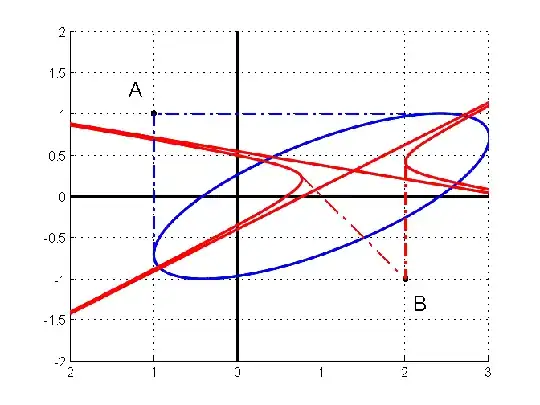

(see figure) @wojowu @Blue @Shreyash Chaudhari

Here is a mathematical explanation, using projective geometry.

Let us consider the case of an ellipse : from a given point outside an ellipse, you can draw two tangents (only).

If you have done projective geometry, you know that one can transform any conic section into any other one, in particular, one can map a hyperbola onto an ellipse, and vice versa.

As contact points and their tangents are preserved in such a transform, we are done.

With an example, it will be better; consider projective transform (P):

$$\begin{cases}X=\dfrac{2x}{x+y-1}\\Y=\dfrac{y}{x+y-1}\end{cases}$$

(P) "sends" the ellipse onto the hyperbola, sends $A(x,y)=(-1, 1)$ onto $B(X,Y)=(2,-1)$ and maps the tangents issued from $A$ to the ellipse onto the tangents issued from $B$ to the hyperbola.

I give below the Matlab program that I have done for this picture.

clear all;close all;hold on; grid on;

set(gcf,'color','w');

set(0,'defaulttextfontsize',16);

set(0,'defaultlinelinewidth',2);

axis([-2,3,-2,2]);

Tx=@(x,y)(2*x./(x+y-1)); % proj. transf. equ.

Ty=@(x,y)(y./(x+y-1)); % contd

t=0:0.01:2*pi;

x=1+2*cos(2*t-pi/4); % ellipse's param. equ.

y=sin(2*t); % contd

plot(x,y);

plot(Tx(x,y),Ty(x,y),'r')

x=[-1,-1,2.4];y=[-0.7,1,1];

plot(x,y,'-.b'); % draw tangents to ellipse issued from A

plot(Tx(x,y),Ty(x,y),'-.r'); % draw tangents to hyperbola issued from B

scatter([-1,2],[1,-1],30,'filled','k')

text(-1.3,1.3,'A');text(2.1,-1.3,'B');

- 88,997