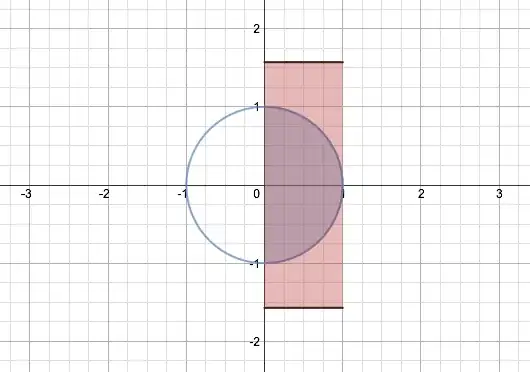

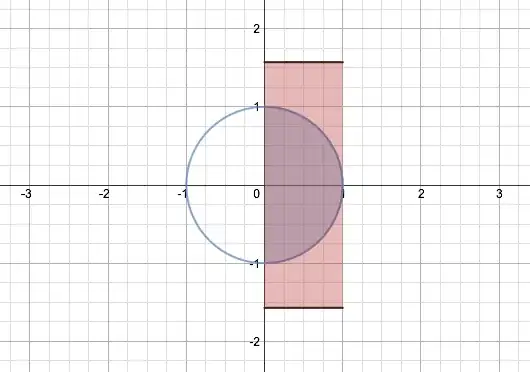

Let's begin with a geometric interpretation that is, admittedly, a little contrived, but may give some satisfaction. Consider a circle, and construct a rectangle whose width is one of the circle's radii. If we extend the black lines outward until the two orange areas together have the same area as the purple semicircle, the length of the rectangle is $\pi$ times its width:

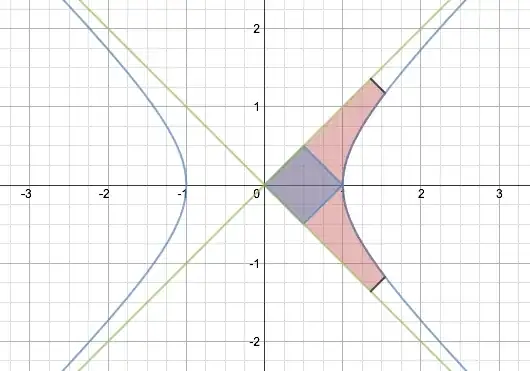

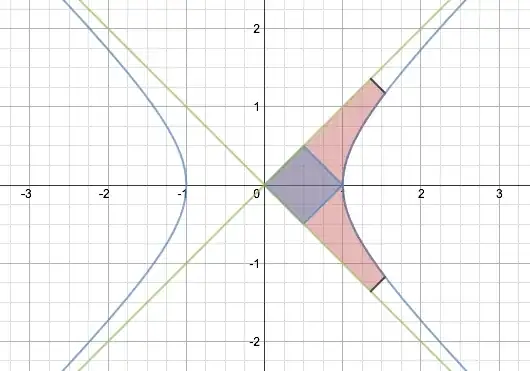

Next, consider a right hyperbola (that is, one in which the asymptotes are at right angles). If we extend the black lines outward until each of the orange areas individually have the same area as the purple square, those black lines are each $e$ times as far out from the center as the side of the square:

Now, some other observations:

Remember that hyperbolic sine and cosine are defined as

$$

\cosh\phi = \frac{e^\phi+e^{-\phi}}{2}

$$

$$

\sinh\phi = \frac{e^\phi-e^{-\phi}}{2}

$$

so that $e$ is as important to these functions as $\pi$ is to ordinary sine and cosine.

The unit circle $x^2+y^2 = 1$ can be parametrized as $(\cos\theta, \sin\theta)$, and then the area of the sector subtended at the center by the circle, from $0$ to $\theta$, is $\theta/2$. Similarly, the unit hyperbola $x^2-y^2 = 1$ can be parametrized as $(\cosh\phi, \sinh\phi)$, and then the area of the sector subtended at the center by the hyperbola, from $0$ to $\phi$, is $\phi/2$.

Equivalently, just as we have $\cos^2\theta+\sin^2\theta = 1$, we have $\cosh^2\phi-\sinh^2\phi = 1$.

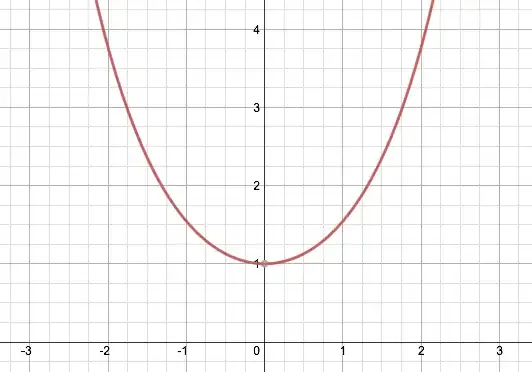

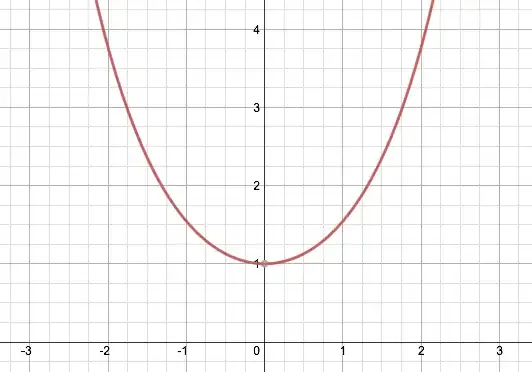

The figure produced by a hanging chain of uniform density is called a catenary (from Latin catena "chain"), and is simply $y = \cosh x$: