Another method.

$$\int_{-\infty}^\infty\exp(ix^2)\mathrm dx=2\int_0^{\infty} \exp(ix^2)\mathrm dx\tag{1}$$

Let $-z=ix^2\implies x=(iz)^{1/2}\implies \mathrm dx=\frac{i^{1/2}}{2}z^{-1/2}\mathrm dz$ hence

$$\int_0^{\infty} \exp(ix^2)\mathrm dx=\frac{i^{1/2}}{2}\int_0^{-i\infty}z^{-1/2}\exp(-z)\mathrm dz\tag{2}$$

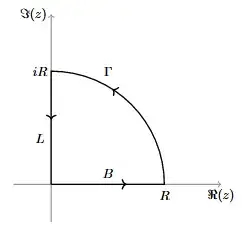

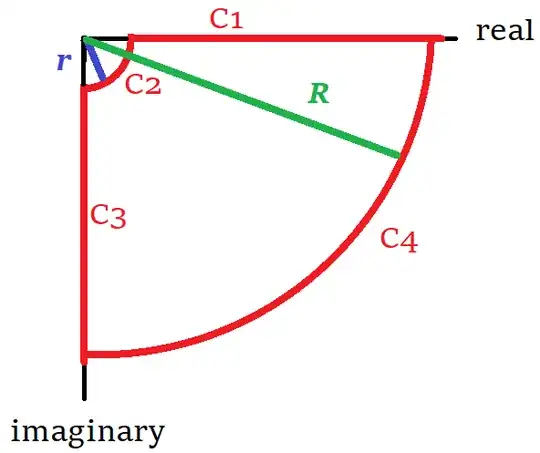

This is almost the Gamma function, but the limits of integration are wrong. We need to somehow argue that we can switch the $\int_0^{-i\infty}$ to $\int_0^\infty$. We consider the following contour in the complex plane:

We call this closed contour $C(r,R)$, a union of the four curves $C_1,C_2,C_3,C_4~(r,R)$. Explicitly,

$$C_1(r,R)=\{t\mid t\in[R,r]\} \\ C_2(r)=\{re^{it}\mid t\in[0,-\pi/2]\} \\ C_3(r,R)=\{-it\mid t\in[r,R]\} \\ C_4(R)=\{Re^{it}\mid t\in[3\pi/2,2\pi]\} \\ C(r,R)=C_1(r,R)\cup C_2(r)\cup C_3(r,R)\cup C_4(R)$$

Because we have an integrand that is analytic everywhere in the interior and on the boundary of $C(r,R)$, we know that

$$\oint\limits_{C(r,R)}z^{-1/2}\exp(-z)\mathrm dz=0$$

Obviously, what we'd like to show is that the integrals on $C_2$ and $C_4$ go to $0$ as $r\to 0,R\to\infty$. Let's have a look at $C_2$ first. Being that the integration goes in the counter-clockwise direction, we actually traverse $C_2$ in the clockwise direction and so we can parameterize the integration along $C_2$ as

$$\int\limits_{C_2(r)}z^{-1/2}\exp(-z)\mathrm dz=\int_{0}^{-\pi/2}(re^{it})^{-1/2}\exp(-re^{it})ire^{it}\mathrm dt$$

Simplifying things a little,

$$\int\limits_{C_2(r)}z^{-1/2}\exp(-z)\mathrm dz=-ir^{1/2}\int_{0}^{\pi/2}e^{it/2}\exp(-re^{-it})\mathrm dt$$

As $r\to 0$ we use a Taylor expansion on the $\exp$:

$$\exp(-re^{-it})=1-re^{-it}+\mathrm O(r^2)$$

So

$$\int\limits_{C_2(r)}z^{-1/2}\exp(-z)\mathrm dz=-ir^{1/2}\int_{0}^{\pi/2}e^{it/2}\exp(-re^{-it})\mathrm dt \\ =-ir^{1/2}\int_0^{\pi/2}e^{it/2}\mathrm dt+ir^{1/2}\int_0^{\pi/2}e^{it/2}re^{it}\mathrm dt +\mathrm O(r^2)\\ =ir^{1/2}\cdot(\text{integral not depending on}~r)+ir^{3/2}\cdot(\text{integral not depending on}~r)+\mathrm O(r^2) \\ =\mathrm O(r^{1/2})\to 0~\text{as}~r\to 0.$$

Now we look at $C_4$. This path is indeed counter-clockwise so we parameterize as such:

$$\int\limits_{C_4(R)}z^{-1/2}\exp(-z)\mathrm dz=\int_{3\pi/2}^{2\pi}(Re^{it})^{-1/2}\exp(-Re^{it})iRe^{it}\mathrm dt \\ =iR^{1/2}\int_{3\pi/2}^{2\pi}e^{it/2}\exp(-Re^{it})\mathrm dt$$

Expanding with Euler's formula,

$$\int\limits_{C_4(R)}z^{-1/2}\exp(-z)\mathrm dz=iR^{1/2}\int_{3\pi/2}^{2\pi} e^{it/2}\exp(-R\cos t-iR\sin t)\mathrm dt \\ =iR^{1/2}\int_{3\pi/2}^{2\pi} e^{it/2}\exp(-R\cos t)\exp(-iR\sin t)\mathrm dt $$

We know that $|\exp(-iR\sin t)|=|e^{it/2}|=1$ and so via the estimation lemma we know that

$$\left|\int_{C_4(R)}z^{-1/2}\exp(-z)\mathrm dz\right|= R^{1/2}\left|\int_{3\pi/2}^{2\pi} e^{it/2}\exp(-R\cos t)\exp(-iR\sin t)\mathrm dt\right| \\ \leq R^{1/2}\left|\int_{3\pi/2}^{2\pi}\exp(-R\cos t)\mathrm dt\right|\tag{3}$$

Past this point, the simple bound from the estimation lemma is actually not enough here, as it would only give us

$$\left|\int_{C_4(R)}z^{-1/2}\exp(-z)\mathrm dz\right|\leq \frac{\pi}{2}R^{1/2}$$

Which still goes to $\infty$ as $R\to \infty$. So we need to find a better way to bound the integral $\int_{3\pi/2}^{2\pi}\exp(-R\cos t)\mathrm dt$.

Due to periodicity,

$$\int_{3\pi/2}^{2\pi}\exp(-R\cos t)\mathrm dt=\int_{-\pi/2}^{0}\exp(-R\cos t)\mathrm dt$$

And then the evenness of the integrand,

$$\int_{-\pi/2}^{0}\exp(-R\cos t)\mathrm dt=\int_0^{\pi/2}\exp(-R\cos t)\mathrm dt$$

Here we will need to consult some mathematical literature. It turns out that

$$\int_0^{\pi/2}\exp(-R\cos t)\mathrm dt=-\frac{\pi}{2}M_0(R)$$

Where $M_0$ is a zeroth-order Modified Struve function. It has the asymptotic expansion

$$M_0(z)\asymp\frac{-1}{2\pi z}+\mathrm O(|z|^{-2}) \\ \text{as}~|z|\to\infty\\ (\operatorname{Re}z>0)$$

Which means, going back to $(3)$,

$$\left|\int_{C_4(R)}z^{-1/2}\exp(-z)\mathrm dz\right|\leq R^{1/2}\frac{\pi}{2}M_0(R)\asymp \frac{1}{4R^{1/2}}$$

Which allows us to conclude

$$\left|\int_{C_4(R)}z^{-1/2}\exp(-z)\mathrm dz\right|\to 0 \\ \text{as}~R\to\infty$$

Therefore,

$$0=\oint_{C(r,R)}z^{-1/2}\exp(-z)\mathrm dz =\left(\int\limits_{C_1(r,R)}+\int\limits_{C_2(r)}+\int\limits_{C_3(r,R)}+\int\limits_{C_4(R)}\right)z^{-1/2}\exp(-z)\mathrm dz \\ \to \left(\int\limits_{C_1(r,R)}+\int\limits_{C_3(r,R)}\right)z^{-1/2}\exp(-z)\mathrm dz~~\text{as}~r\to 0~,~R\to\infty$$

This finally allows us to conclude

$$\int_0^{-i\infty}z^{-1/2}\exp(-z)\mathrm dz=-\int_\infty^0 z^{-1/2}\exp(-z)\mathrm dz \\ =\int_0^\infty z^{1/2-1}\exp(-z)\mathrm dz \\ =\Gamma(1/2)=\sqrt{\pi}$$

Going all the way back to the beginning, this means

$$\int_{-\infty}^\infty\exp(ix^2)\mathrm dx=i^{1/2}\sqrt{\pi}=\sqrt{\frac{\pi}{2}}+i\sqrt{\frac{\pi}{2}}$$

Which instantly gives us the famous Fresnel Integrals:

$$\boxed{\int_{-\infty}^\infty \cos(x^2)\mathrm dx=\int_{-\infty}^\infty \sin(x^2)\mathrm dx=\sqrt{\frac{\pi}{2}}}$$

While lengthier than the other responses, this answer is, in my opinion, far more direct than the others and I think is an accurate reflection of the calculations one would have to go through if one had not seen the problem beforehand. It's my first full attempt at solving this problem, anyhow.