I am looking for a set in the plane (with respect to the natural Euclidean topology) that is connected, locally connected, path-connected but not locally path-connected. I did not find one in Steen-Seebach, but maybe I overlooked?

-

3Do you know of an example in $\mathbb{R}^n$ for any $n$? – Eric Wofsey Oct 27 '15 at 02:36

-

This is interesting. I can think of examples in $\mathbb{R}^3$, but not in $\mathbb{R}^2$. – George Lowther Oct 27 '15 at 20:23

-

1Could you share these examples with the readers of this forum? – R2M Oct 27 '15 at 20:49

-

@R2M: I just did – George Lowther Oct 27 '15 at 23:25

5 Answers

Update: This example is from pp. 184-185 of M. Shimrat, Simply disconnectible sets, Proc. London Math. Soc. (3) 9 (1959), 177-188.

Here is an example I saw in an old paper, maybe from the 1950s. Unfortunately I don't know the reference.

Let $S(a,b)$ be the closed semicircle in the upper half-plane with endpoints $(a,0)$ and $(b,0).$

Let $\mathcal P$ be the smallest set of ordered pairs of real numbers such that $(0,1)\in\mathcal P$ and, whenever $(a,b)\in\mathcal P,$ we have $\left(\frac{a+nb}{n+1},\frac{a+(n+1)b}{n+2}\right)\in\mathcal P$ for $n\in\mathbb N=\{1,2,3,\dots\}.$

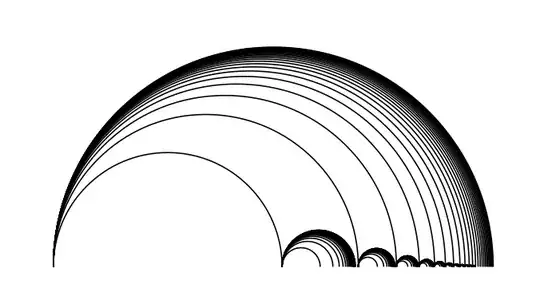

For $a,b\in\mathbb R,\ a\lt b,$ let $$E(a,b)=\bigcup_{n\in\mathbb N}S\left(a,\frac{a+nb}{n+1}\right).$$ Then the set $$X=\bigcup_{(a,b)\in\mathcal P}E(a,b)$$ is pathwise connected and locally connected, but it is not locally pathwise connected.

Added by Grumpy Parsnip: Here is a picture of the first two stages. I hope this is now correct:

And here is a picture I did freehand in Adobe illustrator to try and capture more of the stages and indicate that the limit circles are not in the set. The dotted lines indicate that the limit is not there.

And here is a picture I did freehand in Adobe illustrator to try and capture more of the stages and indicate that the limit circles are not in the set. The dotted lines indicate that the limit is not there. ]2

]2

- 82,298

-

Very nice construction btw, but can you prove it satisfies the properties? (I think I can do this, although it is tricky) – George Lowther Oct 28 '15 at 10:26

-

2@GeorgeLowther No, I I can't prove it has the properties. (Maybe I could if my life depended on it, I don't know.) I was hoping that I could find the reference, so I would be absolved from proving anything. Please post your own answer with the construction I posted (I don't own it) and a proof that it works, and I will delete my answer. – bof Oct 28 '15 at 10:39

-

If you don't find a reference I'll post an answer later today or tomorrow, although no need to delete yours. – George Lowther Oct 28 '15 at 10:44

-

Post your answer whenever you're ready, I don't expect to find the reference anytime soon. I hope somebody finds it eventually, in order to set the record straight and give credit where due. Maybe I should ask that as a reference-request question. – bof Oct 28 '15 at 10:52

-

-

I think I've got a pretty good picture of this set, but I'm not seeing why it is not locally path connected, even informally. – Cheerful Parsnip Oct 28 '15 at 13:47

-

@Grumpy Parsnip: Basically, it is a tree and every path from one node to another node in a different branch must visit a node above those two, and local path connectedness fails because each node (other than the top one) is a limit of nodes in different branches. – George Lowther Oct 28 '15 at 14:44

-

@GeorgeLowther: I see it's tree like structure, and I see all sorts of limiting of nodes onto nodes, but I'm still not seeing why local path connectedness fails. Isn't a neighborhood of a node just a truncated tree? – Cheerful Parsnip Oct 28 '15 at 15:11

-

@GeorgeLowther I think you're right about $\bar S(0,1)$ not being needed. I recall now that that wasn't in the original picture in the article I read.. I added that myself (some decades ago) in order to get an example of a locally connected & pathwise connected & simply connected space with a proper covering space. Or something like that. – bof Oct 28 '15 at 18:04

-

@R2M I'm sorry. I would have loved to post a picture instead of that ugly definition. Sadly, I don't know how to post pictures, and I would have a hard time drawing it on paper as I can't draw freehand circles. Anybody who wants to edit a picture of that thing into my answer has my blessing. – bof Oct 28 '15 at 18:10

-

-

1@GrumpyParsnip Much better. Thanks! It's not clear from the picture that the "limit" semicircles from 0 to 1, from 1/2 to 2/3, etc. are not in the set. I'm not sure what would be a good way to indicate that in a picture. – bof Oct 28 '15 at 21:44

-

@GrumpyParsnip Now that you're looking at the right picture, do you see "informally" that it's locally connected but not locally pathwise connected? I mean, does it look plausible now? – bof Oct 28 '15 at 21:45

-

@bof: I'm definitely much more convinced it's true and now I understand George Lowther's comment about backtracking to a higher node. The point is that that higher node is not in a small neighborhood of the point your are looking at. – Cheerful Parsnip Oct 28 '15 at 22:12

-

-

@R2M Endpoints included, that's what I meant by "closed" semicircle. Seems to me you have to include them if you want the whole set to be pathwise connected. Anyway, now that I've found and posted the Shimrat reference, you're better off reading his paper and ignoring my clumsy and perhaps inaccurate attempt to reproduce it from memory. – bof Oct 29 '15 at 09:07

-

Let us note that $X$ presents a sort of "self-similarity" in the following sense. For every $\alpha, \beta \in \mathbb{R}, \alpha < \beta$, let $\mathcal{P}(\alpha, \beta)$ be the smallest subset of $\mathbb{R}^2$ such that $(\alpha, \beta) \in \mathcal{P}(\alpha, \beta)$ and , whenever $(a,b) \in \mathcal{P}(\alpha, \beta)$ we have $\left(\frac{a+nb}{n+1},\frac{a+(n+1)b}{n+2}\right)\in\mathcal P(\alpha, \beta)$ for $n\in\mathbb N={1,2,3,\dots}.$ The set $\mathcal{P}$ defined in the answer of @bof coincides with $\mathcal{P}(0,1)$. – Maurizio Barbato Aug 06 '23 at 10:46

-

For any $\alpha, \beta \in \mathbb{R}, \alpha < \beta$, set $X(\alpha, \beta) = \bigcup_{(a,b) \in \mathcal{P}(\alpha,\beta)} E(a,b)$. $X(0,1)$ coincides with $X$. Moreover $X(\alpha, \beta)$ is similar to $X$. This follows just at once by noticing that for every $a, b \in \mathbb{R}, a < b$, and every $n \in \mathbb{N}$, we have $\left(\frac{a+nb}{n+1},\frac{a+(n+1)b}{n+2}\right)=(a+\frac{n(b-a)}{n+1}, a+\frac{(n+1)(b-a)}{n+2})$. In particular, if $(\alpha,\beta) \in \mathcal{P}$, we have that $X(\alpha,\beta)$ is a subset of $X$ similar to $X$. – Maurizio Barbato Aug 06 '23 at 10:52

I'm posting this answer in order to show that the excellent example given by bof does satisfy the required properties - it is path connected and locally connected, but not locally path connected. See that answer for a construction of the set and for plots of it.

As I am not adding any new examples of my own, I'll make this answer community wiki so others can edit it.

I'll start by constructing the set in slightly different way which should represent the tree-like nature of the set a bit better. First, a bit of notation. Use $\mathbb{N}=\{1,2,\ldots\}$ for the positive integers, and $\mathbb{N}^*=\bigsqcup_{n=0}^\infty\mathbb{N}^n$ for the collection of finite sequences of positive integers. For any $a=(a_1,\ldots,a_m)$, $b=(b_1,\ldots,b_n)$ in $\mathbb{N}^*$ and $k\in\mathbb{N}$ then I will write $a\cdot k=(a_1,\ldots,a_m,k)$ $a\cdot b=(a_1,\ldots,a_m,b_1,\ldots,b_n)$. We can also put the lexicographic order on $\mathbb{N}^*$, so that $a\le b$ iff there is a $j\le\min(m,n)$ with $a_i=b_i$ for all $i < j$ and $a_j < b_j$, or if $m\le n$ and $a_i=b_i$ for all $i\le m$.

Now, let $\{x_a\}_{a\in\mathbb{N}^*}$ be real numbers with the following properties,

- For any $a\in\mathbb{N}^*$ then $k\mapsto x_{a\cdot k}$ is a strictly increasing sequence strictly bounded below by $x_a$.

- For any $a=(a_1,\ldots,a_n)$ with $n\ge1$, then $x_{a\cdot k}\to x_{a^\prime}$ as $k\to\infty$, where $a^\prime=(a_1,\ldots,a_{n-1},a_n+1)$.

These properties are equivalent to saying that $a\mapsto x_a$ is strictly increasing and order-continuous w.r.t. the lexicographic order. Letting $S(x,y)$ be the closed semicircle in the upper half-plane with endpoints $(x,0)$ and $(y,0)$, we define the set $$ X=\bigcup_{a\in\mathbb{N}^*,k\in\mathbb{N}}S(x_a,x_{a\cdot k}). $$ I will use $P_a$ to denote the point $(x_a,0)$, so that $X$ intersects the x-axis precisely at the points $\{P_a\colon a\in\mathbb{N}^*\}$. We can show that $X$ is path connected and locally connected, but is not locally path connected at the points $(x_a,0)$ whenever $a=(a_1,\ldots,a_n)$ with $n\ge1$ and $a_n\ge2$.

The following example gives the same set $X$ as in bof's answer.

- $x_{()}=0$,

- $x_{(k)}=k/(k+1)$.

- $x_{a\cdot k}=(x_{a}+kx_{a^\prime})/(k+1)$ for all $a=(a_1,\ldots,a_n)$ with $n\ge1$, $k\in\mathbb{N}$ and $a^\prime=(a_1,\ldots,a_{n-1},a_n+1)$.

We can prove the following statements.

$X$ is path connected.

By definition, each point of $X$ is connected via an arc of a semicircle to a point $P_{(a_1,\ldots,a_n)}$. This is in turn connected to $P_{(a_1,\ldots,a_{n-1})}$ by a semicircular arc and, applying this inductively, we see that each point of $X$ is connected to $P_{()}$ by a sequence of arcs of semicircles.

The semicircles $S(x_a,x_{a\cdot k})$ minus their endpoints ($P_a,P_{a\cdot k}$) are open in $X$.

This should be clear from the plot of $X$ in bof's answer. If $k > 1$ then it can be seen that the region bounded above by the semicircular arc $S(x_a,x_{a\cdot (k+1)})$ and below by the semicircle $S(x_a,x_{a\cdot(k-1)})$, $S(x_{a\cdot(k-1)},x_{a\cdot k})$ and $S(x_{a\cdot k},x_{a\cdot(k+1)})$ is an open subset of the plane intersecting $X$ at $S(x_a,x_{a\cdot k})$ minus its endpoints. In the case where $k=1$, we can bound the region from below by the line segment joining $P_a$ to $P_{a\cdot k}$ and the semicircle $S(x_{a\cdot k},x_{a\cdot(k+1)})$.

Let $D$ be an open disc centered on the x-axis. Then $D\cap X$ is connected.

Let $S$ be a nonempty set which is open and closed on $D\cap X$. We need to show that it is all of $D\cap X$. Note that each of the semicircles defining $X$ intersects $D$ in an arc (i.e., connected) meeting one of the points $P_a$, if it intersects it at all. So, $P_a\in S$ for some $a$. We just need to show that $S$ contains all of the points $P_a$ which are in $D$. I'll show that if $a\le b$, $P_a\in S$ and $P_b\in D$ then $P_b\in S$. Applying the same statement to the complement of $S$ will show that it also holds for $a \ge b$, which gives the result.

If $P_a\in S$ and $P_{a\cdot k}\in D$ then the semicircle joining $P_a$ to $P_{a\cdot k}$ lies in $D\cap X$, so $P_{a\cdot k}\in S$. Next, if $a= (a_1,\ldots,a_n)$ has $n\ge1$ and $a^\prime=(a_1,\ldots,a_n+1)$ satisfies $P_{a^\prime}\in D$ then $P_{a^\prime}=\lim_{k\to\infty}P_{a\cdot k}\in S$. Inductively applying this gives $P_{(a_1,\ldots,a_n+k)}\in S$ whenever it is in $D$.

Now consider $a=(a_1,\ldots,a_m)$ and $b=(b_1,\ldots,b_n)$ with $a\le b$, $P_a\in S$ and $P_b\in D\cap X$. If $m\le n$ and $a_i=b_i$ for $i\le m$ then we have $P_{(b_1,\ldots,b_m)}=P_a\in S$. Using the above, we can inductively apply $P_{(b_1,\ldots,b_{m+1})}=P_{(b_1,\ldots,b_m)\cdot b_{m+1}}\in S$. to see that $P_b\in S$.

Finally, consider the case where for some $j\le\min(m,n)$ we have $a_i=b_i$ for all $i < j$ and $a_j < b_j$. From what we have shown above, $$ P_{(a_1,\dots,a_{m-1}+1)}=\lim_{k\to\infty}P_{(a_1,\dots,a_{m-1},a_m+k)}\in S. $$ Inductively applying this gives $P_{(a_1,\ldots,a_{j-1},a_j+1)}\in S$. Then, as $b_j=a_j+1+k$ for some $k\ge0$, applying what we have shown above gives $P_{(b_1,\ldots,b_j)}\in S$. Then, using the first case, we have $P_b\in S$.

$X$ is locally connected

Each point of $X$ not on the x-axis lies on one of the semicircles $S(x_a,x_{a\cdot k})$ minus its endpoints which we have shown to be open in $X$. So, $X$ is locally (path) connected away from the x-axis. Next, any point on the x-axis has a base of connected neighborhoods by taking the open discs centered at the point intersected with $X$.

For any $a=(a_1,\ldots,a_n)$ with $n\ge1$ and $a_n \ge 2$, $X$ is not locally path connected at $P_a$.

This remains to be added...

- 34,429

-

The proof of the final statement (remains to be added...) is obviously one of the main points of this construction, so I'll add it when I have some time. Tomorrow, hopefully. – George Lowther Oct 29 '15 at 00:32

-

2

Here's an example in $\mathbb{R}^3$. The construction does not adapt to the plane, and I don't know if there do exist examples in $\mathbb{R}^2$.

Start by letting $A\subseteq\mathbb{R}^2$ be connected, locally connected and not locally path connected. For example, see my answer on mathoverflow for an example where $A$ is totally path disconnected (i.e., every continuous $f\colon\mathbb{R}\to A$ is constant), so has no path connected subsets other than single points.

Then, $$ X = \left\{(x,y,z)\in\mathbb{R}^3\colon (y,z)\in A{\rm\ or\ }x=0\right\} $$ is connected, locally connected, path connected but not locally path connected.

To see this, set \begin{align} Y &= \mathbb{R}\times A = \left\{(x,y,z)\in\mathbb{R}^3\colon (y,z)\in A\right\},\\ Z&=\{0\}\times\mathbb{R}^2=\left\{(x,y,z)\in\mathbb{R}^3\colon x=0\right\} \end{align} so that $X=Y\cup Z$. Then, $Y$ is locally connected, as $\mathbb{R}$ and $A$ satisfy these properties. So, $X$ is locally connected away from $Z$. Furthermore, we have a deformation retraction from $X$ onto $Z$ by $F((x,y,z),t)=(tx,y,z)$, so $X$ is contractible and, hence, path connected. Restricting to a neighbourhood of any point in $Z$, this also shows that $X$ is locally contractible at all points of $Z$, so $X$ is locally connected. However, if $A$ is not locally path connected at a point $p\in A$ then $X$ cannot be path connected about any point $(x,p)\in X$ for all $x\not=0$.

- 34,429

I shall complete here the answer given by George Lowther by proving its last statement. Clearly, all the terminology and notation will be that used by George Lowther in his answer (in particular $()$ will denote the empty sequence in $\mathbb{N}^*$, that is the sequence of zero length, and if $a=(a_1,\ldots,a_n) \in \mathbb{N}^n$ for some $n \geq 1$, we shall agree that $(a_1,\ldots,a_{n-1})$ is equal to the empty sequence $()$ when $n=1$.). Moreover, we shall need some further notation in order to carry on the proof.

For every $x, y \in \mathbb{R}^2$, we denote by $d(x,y)$ the usual euclidean distance between $x$ and $y$, while for every $x \in \mathbb{R}^2$ and every $r > 0$, $D_r(x)$ will denote the open disc of center $x$ and radius $r$. For every $a \in \mathbb{N}^*$, by $\mathcal{B}(a)$ we shall denote the branch of $X$ starting at $P_a$, that is $$ \mathcal{B}(a)= \bigcup_{b \in \mathbb{N}^{*},k\in\mathbb{N}} S(x_{a \cdot b}, x_{a \cdot b \cdot k}). $$ We shall also set for every $a \in \mathbb{N}^{*},k\in\mathbb{N}$: $$ \mathcal{C}(a,k)=S(x_a,x_{a \cdot k}) \cup \mathcal{B}(a \cdot k). $$ Finally, for every $a, b \in \mathbb{R}, a < b$, we shall denote by $\mathcal{R}(a,b)$ the closed region of the plane bounded from above by $S(a,b)$ and bounded from below by the segment of extremes $(a,0)$ and $(b,0)$.

The main part of the proof is the following proposition.

For any $a \in \mathbb{N}^{*}$, the path components of $X \setminus \{ P_a \}$ are each of the sets $\mathcal{C}(a,k) \setminus \{ P_a \}$, for $ k \in \mathbb{N}$, and, when $a \neq ()$, also the set $X \setminus \mathcal{B}(a)$.

Let us first of all note that, by arguing as done by George Lowther in his proof that $X$ is path connected, we see that $X \setminus \mathcal{B}(a)$ (when $a$ is not the empty sequence, otherwise $X \setminus \mathcal{B}(a) = \emptyset$) as well as each set $\mathcal{C}(a,k) \setminus \{ P_a \}$ for $ k \in \mathbb{N}$ is path connected. In order to prove the proposition, it will then be enough to prove that given $x \in S(x_{a}, x_{a \cdot k}) \setminus \{ P_a \} $ and $y \in S(x_{a}, x_{a \cdot \ell}) \setminus \{ P_a \}$, with $k, \ell \in \mathbb{N}, k < \ell$ (respectively $x \in S(x_{a}, x_{a \cdot k}) \setminus \{ P_a \}$ and $y \in X \setminus \mathcal{B}(a)$), $x$ and $y$ are not path connected in $X \setminus \{ P_a \} $. We shall argue by contradiction. Assume that $f:[0,1] \rightarrow X \setminus \{ P_a \} $ is a continuous map such that $f(0)=x$ and $f(1)=y$. Define $$ T_1= \{ t \in [0,1] : f(t) \in \mathcal{R}(x_a,x_{a \cdot k}) \}. $$ Since $0 \in T_1$, $f$ is continuous and $\mathcal{R}(x_a,x_{a \cdot k})$ is closed, the number $$ t_1=\max T_1 $$ is well defined. Now note that, being $k < \ell$, we have $$ (S(x_a,x_{a \cdot \ell}) \setminus \{ P_a \}) \cap \mathcal{R}(x_a,x_{a \cdot k})= \emptyset, $$ (respectively, being $X \setminus \mathcal{B}(a) = \emptyset$ if $a=()$, while $X \setminus \mathcal{B}(a) \subset \mathbb{R}^2 \setminus (\mathcal{R}(x_a,x_{a'}) \setminus \{ P_{a'} \})$ if $a=(a_1,\ldots,a_{m})$, with $m \geq 1$, and $a'=(a_1,\ldots,a_{m - 1}, a_m + 1)$, we have $$ (X \setminus \mathcal{B}(a)) \cap \mathcal{R}(x_a,x_{a \cdot k})= \emptyset), $$ so that $f(1)=y \notin \mathcal{R}(x_a,x_{a \cdot k})$, which implies $t_1 < 1$. By the continuity of $f$, $f(t_1)$ must belong to the boundary of $\mathcal{R}(x_a,x_{a \cdot k})$ (for otherwise $f(t)$ would belong to the interior of $\mathcal{R}(x_a,x_{a \cdot k})$, so that we would have $f(t) \in \mathcal{R}(x_a,x_{a \cdot k})$ for all $t \in (t_1, t_1 + \epsilon)$ for $\epsilon > 0$ small enough, against the definition of $t_1$), so either $f(t_1) \in S(x_a,x_{a \cdot k})$ or $f(t_1)$ belongs to the segment $P_a P_{a \cdot k}$ of extremes $P_a$ and $P_{a \cdot k}$. Assume that $f(t_1) \in S(x_a,x_{a \cdot k}) \setminus \{ P_a, P_{a \cdot k} \}$ or that $f(t_1) \in P_a P_{a \cdot k} \setminus \{ P_a, P_{a \cdot k } \}$. Then there would exist $r > 0$ such that $$ D_r(f(t_1)) \cap X \subset \mathcal{R}(x_a,x_{a \cdot k}). $$ Indeed, if $f(t_1) \in S(x_a,x_{a \cdot k}) \setminus \{ P_a, P_{a \cdot k} \}$ we have $D_r(f(t_1)) \cap X \subset S(x_a,x_{a \cdot k}) \setminus \{ P_a, P_{a \cdot k} \} $ for $r$ small enough, being $S(x_a,x_{a \cdot k}) \setminus \{ P_a, P_{a \cdot k} \}$ open in $X$,as already proved by George Lowther in his answer; while if $f(t_1) \in P_a P_{a \cdot k} \setminus \{ P_a, P_{a \cdot k } \}$, just choose $r < \min \{ d(f(t_1),P_a),d(f(t_1),P_{a \cdot k}) \}$. But then by the continuity of $f$ there would exist $\epsilon > 0$ such that for all $t \in (t_1, t_1 + \epsilon)$ we would have $f(t) \in \mathcal{R}(x_a,x_{a \cdot k})$, against the definition of $t_1$. Since $f(t_1) \neq P_a$ by assumption, we conclude that $f(t_1)=P_{ a \cdot k }$. Set $b_1=k$.

Now assume that for some $n \in \mathbb{N}$ we have defined a strictly increasing finite sequence $0 \leq t_1 < t_2 < \ldots < t_n <1$ and $b=(b_1,\ldots,b_n) \in \mathbb{N}^n$, such that for each $i=1,\ldots,n$ we have: $$ f(t_i)=P_{a \cdot (b_1,\ldots,b_i)}, $$ $$ f(t) \notin \mathcal{R}(x_{a \cdot (b_1,\ldots,b_{i-1})}, x_{a \cdot (b_1,\ldots,b_i)}) \quad \forall t \in (t_i,1]. $$ In particular we have $f(t) \neq P_{a \cdot (b_1,\ldots,b_n)}$ for all $t \in (t_n,1]$. Set $$ \delta = \min \{x_{a \cdot (b_1,\ldots,b_{n})} - x_{a \cdot (b_1,\ldots,b_{n-1})}, x_{a \cdot (b_1,\ldots,b_n, 1)} - x_{a \cdot (b_1,\ldots,b_{n})}\}. $$ Since the map $a \mapsto x_a$ from $\mathbb{N}^{*}$ into $\mathbb{R}$ is strictly increasing, we have $\delta > 0$ and $x_{a \cdot (b_1,\ldots,b_n, 1)} < x_{a \cdot (b_1,\ldots,b_{n-1},b_n + 1)}$, so that $$ \delta \leq \min \{x_{a \cdot (b_1,\ldots,b_{n})} - x_{a \cdot (b_1,\ldots,b_{n-1})}, x_{a \cdot (b_1,\ldots,b_{n-1}, b_n +1)} - x_{a \cdot (b_1,\ldots,b_{n})}\}, $$ which in turn implies that $$ D_{\delta}(P_{a \cdot (b_1,\ldots,b_{n})}) \subset \mathcal{R}(x_{a \cdot (b_1,\ldots,b_{n-1})},x_{a \cdot (b_1,\ldots,b_{n-1},b_n + 1)}) \setminus S(x_{a \cdot (b_1,\ldots,b_{n-1})},x_{a \cdot (b_1,\ldots,b_{n-1},b_n + 1)}). $$ Choose then $\epsilon > 0$ such that $f(t) \in D_{\delta}(P_{a \cdot (b_1,\ldots,b_{n})})$ for all $t \in (t_n,t_n + \epsilon)$. Since $$ f(t) \notin \mathcal{R}(x_{a \cdot (b_1,\ldots,b_{n-1})}, x_{a \cdot (b_1,\ldots,b_n)}) \quad \forall t \in (t_n,1 $$ we must have $$ f(t) \in \mathcal{R}(x_{a \cdot (b_1,\ldots,b_{n})}, x_{a \cdot (b_1,\ldots,b_{n-1},b_n + 1)}) \quad \forall t \in (t_n,t_n + \epsilon). $$ By the definition of $\delta$ we also have $\delta \leq x_{a \cdot (b_1,\ldots,b_n, 1)} - x_{a \cdot (b_1,\ldots,b_{n})}$, so that in conclusion we must have $$ f(t) \in \bigcup_{p \in \mathbb{N}} S(x_{a \cdot (b_1,\ldots,b_{n})},x_{a \cdot (b_1,\ldots,b_{n}) \cdot p}) \quad \forall t \in (t_n,t_n + \epsilon). $$ Let then $p \in \mathbb{N}$ be such that for some $\tilde{t} \in (t_n,t_n+\epsilon)$ we have $$ f(\tilde{t}) \in S(x_{a \cdot (b_1,\ldots,b_{n})},x_{a \cdot (b_1,\ldots,b_{n}) \cdot p}). $$ Set $b_{n+1}=p$ and $$ T_{n+1}= \{ t \in [0,1] : f(t) \in \mathcal{R}(x_{a \cdot (b_1,\ldots,b_{n})}, x_{a \cdot (b_1,\ldots,b_{n+1})}) \}. $$ Since $\tilde{t} \in T_{n+1}$, $f$ is continuous and $\mathcal{R}(x_{a \cdot (b_1,\ldots,b_{n})}, x_{a \cdot (b_1,\ldots,b_{n+1})})$ is closed $$ t_{n+1}=\max T_{n+1} $$ is well defined and such that $t_n < t_{n+1}$. Note now that we have $x_a < x_{a \cdot (b_1,\ldots,b_n)}$ and also $x_{a \cdot (b_1,\ldots,b_{n+1})} < x_{a \cdot (k+1)}$, since $b_1=k$, so that $$ \mathcal{R}(x_{a \cdot (b_1,\ldots,b_{n})}, x_{a \cdot (b_1,\ldots,b_{n+1})}) \subset \mathcal{R}(x_a,x_{a \cdot (k+1)}) \setminus S(x_a,x_{a \cdot (k+1)}), $$ from which, being $k < \ell$, we get $$ (S(x_a,x_{a \cdot \ell}) \setminus \{ P_a \}) \cap \mathcal{R}(x_{a \cdot (b_1,\ldots,b_{n})}, x_{a \cdot (b_1,\ldots,b_{n+1})}) = \emptyset, $$ (respectively,being $X \setminus \mathcal{B}(a) = \emptyset$ if $a=()$, while $X \setminus \mathcal{B}(a) \subset \mathbb{R}^2 \setminus (\mathcal{R}(x_a,x_{a'}) \setminus \{ P_{a'} \})$ if $a=(a_1,\ldots,a_{m})$, with $m \geq 1$, and $a'=(a_1,\ldots,a_{m - 1}, a_m + 1)$, we have $$ (X \setminus \mathcal{B}(a)) \cap \mathcal{R}(x_{a \cdot (b_1,\ldots,b_{n})}, x_{a \cdot (b_1,\ldots,b_{n+1})}) = \emptyset). $$ So $f(1)=y \notin \mathcal{R}(x_{a \cdot (b_1,\ldots,b_{n})}, x_{a \cdot (b_1,\ldots,b_{n+1})})$, from which we get $t_{n+1} < 1$. Now, exactly the same argument given above in order to prove that $f(t_1)=P_{a \cdot k}$ with:

$\bullet$ $t_1$ replaced everwhere by $t_{n+1}$,

$\bullet$ $x_a$ replaced everywhere by $x_{a \cdot (b_1,\ldots,b_n)}$,

$\bullet$ $x_{a \cdot k}$ replaced everywhere by $x_{a \cdot (b_1,\ldots,b_{n+1})}$,

$\bullet$ the statement "$f(t_1) \neq P_a$ by assumption" replaced by "$f(t_{n+1}) \neq P_{a \cdot (b_1,\ldots,b_n)}$ since $f(t) \neq P_{a \cdot (b_1,\ldots,b_n)}$ for $t \in (t_n,1]$"

shows that $f(t_{n+1})= P_{a \cdot (b_1,\ldots,b_{n+1})}$.

In this way, we define a strictly increasing sequence $(t_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}$ in $[0,1]$, and a sequence $(b_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}$ with values in $\mathbb{N}$ such that $f(t_n)=P_{a \cdot (b_1,\ldots,b_n)}$ for all $n \in \mathbb{N}$. Since the map $a \mapsto x_a$ from $\mathbb{N}^{*}$ into $\mathbb{R}$ is strictly increasing, the sequence $(x_{a \cdot (b_1,\ldots,b_n)})_{n \in \mathbb{N}}$ is strictly increasing and bounded from above by $x_{a \cdot (b_1 + 1)}$. So there exist the limits $$ \bar{t}=\lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} t_n, $$ and $$ \bar{x}=\lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} x_{a \cdot (b_1,\ldots,b_n)}. $$ By continuity we have $$ \bar{x}=f(\bar{t}) \in X \setminus \{ P_a \}. $$ But this is not possible. Indeed, let $(c_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}$ be the sequence obtained by appending $(b_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}$ to $a$ (that is, if $a=()$, we have $c_n=b_n$ for all $n$, while, if $a=(a_1,\ldots,a_m)$ with $m \geq 1$, we have $c_n=a_n$ for $1 \leq n \leq m$ and $c_n=b_{n-m}$ for $n > m$). Let $d=(d_1,\ldots,d_q) \in \mathbb{N}^{q}$. If there exists $j \leq q$ such that $d_i=c_i$ for $1 \leq i < j$ and $d_j < c_j$, we have $d < (c_1,\ldots, c_q)$, so that $x_d < x_{(c_1,\ldots, c_q)} < \bar{x}$. Analogously, if $d_i=c_i$ for $1 \leq i \leq q$ (this case includes the one in which $q=0$, that is $d$ is the empty sequence), we have $d < (c_1,\ldots, c_{q+1})$ and so $x_d < x_{(c_1,\ldots, c_{q+1})} < \bar{x}$. Finally, if there exists $j \leq q$ such that $d_i=c_i$ for $1 \leq i < j$ and $d_j > c_j$, we have $d > (c_1,\ldots,c_j,c_{j+1} +1)$, so that $x_d > x_{(c_1,\ldots,c_j,c_{j+1} +1)} \geq \bar{x}$. In any case $x_d \neq \bar{x}$, so that $\bar{x} \notin X$, a contradiction.

For any $a=(a_1,\ldots,a_n)$ with $n\ge1$ and $a_n \geq 2$, $X$ is not locally path connected at $P_{a}$.

To prove now this claim is very easy. Set $b=(a_1,\ldots,a_{n-1})$ and $c=(a_1,\ldots,a_{n-1},a_n -1)$. Let $\delta > 0$ be such that $\delta < x_{a} - x_{b}$, and set $N=D_{\delta}(P_{a}) \cap X$. $N$ is a neighborhood of $P_{a}$ in $X$. Assume that $M$ is a neighborhood of $P_{a}$ in $X$ such that $M \subset N$. Then for some $r \in (0,\delta)$ we have $D_r(P_{a}) \cap X \subset M$. Since we have $$ \lim_{k \rightarrow \infty} x_{c \cdot k} = x_{a}, $$ we have $P_{c \cdot k} \in D_r(P_{a}) \cap X \subset M$ for all $k > K$ for some $K > 0$. Choose $k > K$. Now $P_{c \cdot k} \in \mathcal{C}(b,a_n -1) \setminus \{P_b \}$, while $P_{a} \in \mathcal{C}(b,a_n) \setminus \{P_b \}$. By the proposition proved above $P_{c \cdot k}$ and $P_{a}$ are not path connected in $X \setminus \{P_b\}$, and so they are not path connected in $M$. So we conclude that $M$ is not path connected. QED

- 4,220

-

Some final comments. First of all, I apologize if this answer is a little bit too long, but I preferred to write down carefully all the details of the proof, hoping this makes it more readable. This is also the reason I decided not to add it to the original answer of George Lowther. Secondly, I want to thank very very ... much @bof for having acquainted me and all the community with this wonderful example of topological space, which deserves to be named "Shimrat's space": it is a remarkably beautiful object with bizarre topological properties! – Maurizio Barbato Aug 06 '23 at 09:20

-

Finally, I want to express a special thank to @GeorgeLowther for the generosity he showed in sharing his thoughts about Shimrat's space $X$. In particular he did an extraordinarily fine job in: (i) elucidating the tree structure of $X$; (ii) finding a remarkable generalization of its definition; (iii) giving careful proofs of its path connectedness and local connectedness. Thanks a lot, George! – Maurizio Barbato Aug 06 '23 at 09:25

This is not a separate answer, but only a too long observation to be written down as a comment. I use here the same notation used in my answer above. I want to observe here that $X$ allows us to define a another subspace of the plane with unusual topological properties. More precisely, my aim here is to prove the following statement.

Let $a=()$ be the empty sequence. Then $X \setminus \{ P_a \}$ is a subspace of the plane which is connected, locally connected, but not path connected.

Indeed, being $X$ locally connected as proved by George Lowther, also $X \ \setminus \{ P_a \}$ is locally connected. Moreover, by the proposition proved in my answer above, we know that $X \setminus \{ P_a \}$ is not path connected. All we have to prove here is that $X \setminus \{ P_a \}$ is connected. To see this, let $x \in \mathcal{C}(a,k) \setminus \{ P_a \}$ and $y \in \mathcal{C}(a,k+\ell) \setminus \{ P_a \}$, with $k, \ell \in \mathbb{N}$. Since we have

$$

\lim_{m \rightarrow \infty} P_{(k) \cdot m} = P_{(k+1)},

$$

$P_{(k+1)}$ belongs to the closure of $\mathcal{C}(a,k) \setminus \{ P_a \}$. By the proposition in my answer above, $\mathcal{C}(a,k) \setminus \{ P_a \}$ is path connected and so connected. It follows that the set $Y_{0}=(\mathcal{C}(a,k) \setminus \{ P_a \}) \cup \{ P_{(k+1)} \}$ is connected. But since $\mathcal{C}(a,k+1) \setminus \{ P_a \}$ is path connected, and so connected, and $P_{(k+1)} \in \mathcal{C}(a,k+1) \setminus \{ P_a \}$, we have that $Y_{0} \cup (\mathcal{C}(a,k+1) \setminus \{ P_a \})=(\mathcal{C}(a,k) \setminus \{ P_a \}) \cup (\mathcal{C}(a,k+1) \setminus \{ P_a \})$ is connected. Now, assume by induction that, for $1 \leq n < \ell$, the set

$$

\bigcup_{s=0}^{n} (\mathcal{C}(a,k+s) \setminus \{ P_a \})

$$

is connected. Since

$$

\lim_{m \rightarrow \infty} P_{(k+n) \cdot m} = P_{(k+n+1)},

$$

$P_{(k+n+1)}$ belongs to the closure of $\mathcal{C}(a,k+n) \setminus \{ P_a \}$. So by the inductive assumption

$$

Y_{n}= \left( \bigcup_{s=0}^{n} (\mathcal{C}(a,k+s) \setminus \{ P_a \})\right) \cup \{ P_{(k+n+1)} \}

$$

is a connected set. Now $\mathcal{C}(a,k+n+1) \setminus \{ P_a \}$ is path connected, and so connected, and $P_{(k+n+1)} \in \mathcal{C}(a,k+n+1) \setminus \{ P_a \}$, so that

$$

Y_{n} \cup (\mathcal{C}(a,k+n+1) \setminus \{ P_a \})= \bigcup_{s=0}^{n+1} (\mathcal{C}(a,k+s) \setminus \{ P_a \})

$$

is connected. By induction we conclude that

$$

\bigcup_{s=0}^{\ell} (\mathcal{C}(a,k+s) \setminus \{ P_a \})

$$

is a connected subspace of $X \setminus \{ P_a \}$ containing both $x$ and $y$ . So any two points of $X \setminus \{ P_a \}$ are connected in $X \setminus \{ P_a \}$, that is $X \setminus \{ P_a \}$ is connected.

- 4,220