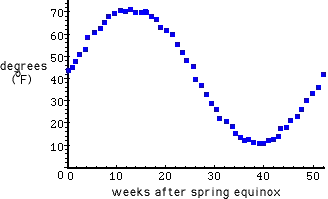

A wide variety of curves are useful in modelling and describing phenomena we observe. Trig functions, logarithms, exponentials, polynomials, hyperbolas, circles, and so forth are all very useful in this regard. As a concrete example, the sine function can be adjusted to model seasonal temperature data, with “time” on the horizontal axis, as has been done in the following image:

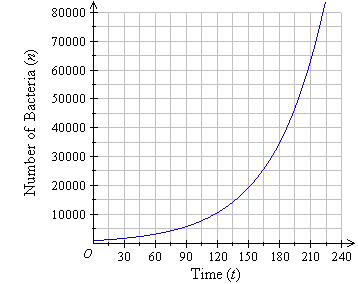

Likewise, exponential functions are well-suited to model population growth in certain scenarios:

However, let us consider when we actually see curves literally appearing in the macroscopic environment, with spatial dimensions on both axes. To list some examples, we see circles reflected in the cross-sections of trees; ellipses (and conic sections in general) are reflected in the orbits of the planets; hyperbolas and parabolas often appear in the context of light; a rock thrown upwards with some horizontal velocity follows a parabolic trajectory; concentric circles are seen around a drop in a pond, etc. In the overwhelming majority of cases I can think of, the only curves that manifest themselves visually in the macroscopic environment with any degree of regularity are the conic sections. Why is this the case? Given that other curves are just as apt and essential in describing the universe, there is no apparent reason why they should not also appear in our environment to the extent conic sections have. What is special about the conic sections?

So far, I have arrived at a few possible explanations, such as the Einsteinian nature of the fabric of space-time and how the presence of mass in space can be visualized by placing weights on a rubber sheet. This gives rise to conic sections appearing astronomically, and the effect filters down into smaller phenomena on a given planet (think, e.g., the Coriolis effect), which can then filter down further into even smaller phenomena. However, none of these possible explanations have yet come close to being particularly satisfactory or widely applicable.

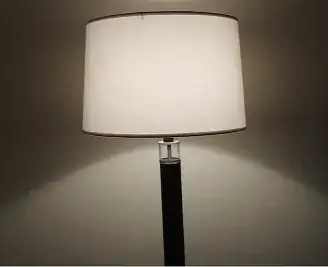

To finish up, I think this thread (and corresponding image below) are appropriate to include for a rather illuminating discussion (no pun intended) as to the various ways conic sections can appear with regards to light.

As one final note, this is not to say that we see only conic sections in nature. For example, catenaries arise in natural settings (e.g. spider webs, see below). The point, however, is that subjectively, conic sections seem to be the most abundant by far.

N.B.: I don't own any of these images. I'm simply hyperlinking from Google search results.

All of the manifestations you can think of, the tree, the pond, the orbits, happen in a setting where the medium is isotropic, and/or forces are radial. There is nothing preventing the tree from thickening radially. The pond has the same linear mass in all directions so the waves propagate at the same speed in all directions. Gravitational pull is radial.

– Mathusalem Oct 08 '15 at 09:23