I have seen similar post asking for interpretation of the Maurer-Cartan form, but I am still struggling to understand it, so let me try to work a specific example and pose a specific question.

Let $G$ be the group containing all matrices of the form

\begin{bmatrix} x &y \\ 0 &1/x \end{bmatrix}

where $x \neq 0$.

I read that the Maurer-Cartan form is defined as $\Omega = g^{-1} dg$ so I computed

$\Omega= \begin{bmatrix} 1/x &-y \\ 0 &x \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} dx &dy \\ 0 &-dx/x^2 \end{bmatrix}= \begin{bmatrix} dx/x &ydx/x^2+dy/x \\ 0 &-dx/x \end{bmatrix}$

So, for example, at the point $g= \begin{bmatrix} 5 &3 \\ 0 &1/5 \end{bmatrix} $ we have $\Omega_g = \begin{bmatrix} dx/5 &3dx/25+dy/5 \\ 0 &-dx/5 \end{bmatrix} $

But I read that at a specific point $g\in G$, the entity $\Omega_g$ is supposed to be a linear map from $T_gG$ to $T_eG$. Looking at what I computed above, I don't see how $\Omega_g$ is a linear map on $T_gG$. For example, what is $\Omega_g (\frac{\partial}{\partial x})$?

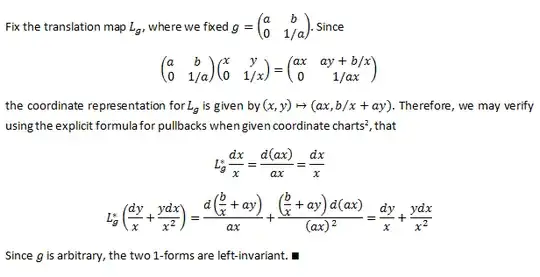

I'm also interested in the claim that $\Omega$ is left-invariant. I am able to show that the 1-forms appearing as entries of $\Omega$ are each left-invariant via explicit computation.

--Proof:

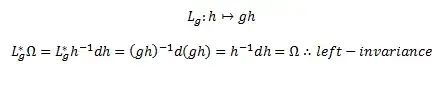

However, I have seen the following "direct" proof, applicable in general, which appears similar in spirit:

--Proof:

However, because $dh$ is not a 1-form in the usual sense, and we are not really working in some coordinates, I am not sure how I am supposed to interpret this "proof" besides recognizing the analogy. Why is the above proof true?

As for background, you may assume I understand Lee's Smooth Manifold text (2nd edition) chapters 1-14. Lee's treatment of 1-form is always real-valued, so this different kind of 1-form is throwing me off.