There isn't anything really wrong with the earlier answers, but I think they missing the chance to articulate a more basic justification of the security of passing IVs in the clear. Which is this:

- If the IV conveys no additional information about the plaintext to an adversary that doesn't already know the key, then knowledge of the IV will not be of significant help to an adversary.

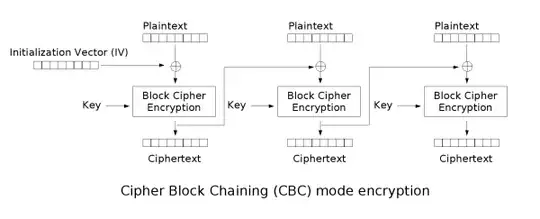

Modes like CBC that require a random IV are the clearest illustration of this. Here's a concrete, physical analogy: if I whimsically decided to toss a coin 128 times and write the outcomes on the outside of a sealed envelope, I think most people would find it obvious that my doing so would be of no help to an adversary trying to deduce the contents of the envelope without actually opening it. Because those 128 coin tosses are obviously random, and thus uncorrelated to the plaintext or any other event.

But the same logic applies to random IVs. They can be passed in the clear because they are random values, and therefore it's guaranteed they don't allow the adversary to infer any other information.

The analogous argument for nonce IVs, on the other hand, is weaker, because it requires us to demonstrate or assume that the honest parties choose nonces such that they do not convey information about the plaintexts (or any other secrets).

There are nuanced objections that have been be raised to the clear transmission of both random and nonce IVs, however. See, for example:

- Bellare, Paterson and Rogaway's work on algorithm substitution attacks, where an adversary performs mass surveillance on a population by covertly substituting an honest random IV algorithm with a dishonest substitute that uses the IV field to exfiltrate an encryption of the keys, but which the honest users cannot tell apart from an honest algorithm. Note that this isn't an argument that a correct implementation of random IVs is unsafe, but rather that protocols that allow such ciphers are vulnerable to a certain class of malicious instantiations.

- Daniel Bernstein's explanation of the optional secret message numbers feature in the CAESAR competition's call for submissions, which is motivated by concerns that in some applications the honest parties' choice of nonce IVs may inadvertently leak information that ought to be kept secret. And therefore submissions were encouraged (but not required) to support secret message numbers, where the cipher provides them with both integrity and confidentiality (like plaintexts) but can demand uniqueness from them (like public message numbers, a.k.a. nonces).