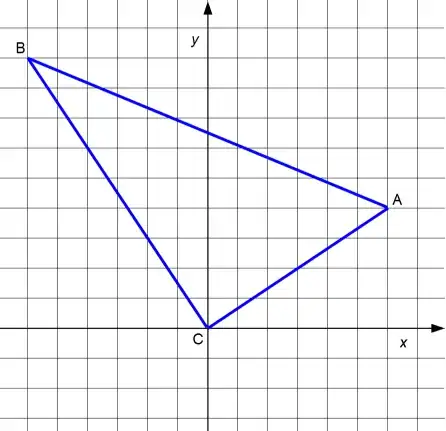

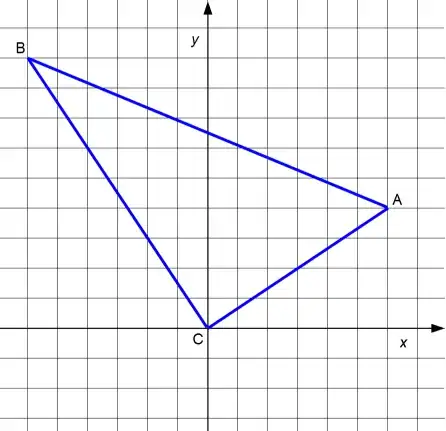

Here's an example of a right triangle with integer coordinates at every vertex

and legs that are not parallel to either coordinate axis:

The vertices of this triangle are $A=(6,4),$ $B=(-6,9),$ and $C=(0,0).$

Now to find out whether a right triangle with given side lengths

can be placed with all three vertices at integer coordinates, let's first try to

determine what right triangles can be constructed on integer coordinates and

what possible sets of lengths their sides can have.

Then we can ask whether the given set of side lengths is one of those possible sets.

First of all, the three side lengths have to satisfy the Pythagorean formula.

List the lengths in order of increasing size, so the lengths are

$AC,$ $BC,$ and $AB$ with $AC \leq BC < AB.$ Then it must be true that

$(AC)^2 + (BC)^2 = (AB)^2.$

If this is false, we do not even have a right triangle.

Now suppose we have three leg lengths as described in the previous paragraph.

Without loss of generality, we can simplify our visualization and calculations

by considering only triangles that (like the one in the figure) have a right

angle at $C=(0,0),$ vertex $A$ in the first quadrant of the plane ($x>0,y>0$),

and vertex $B$ in the second quadrant ($x<0,y>0$).

Any other right triangle with integer coordinates can be translated an integer distance

up or down and an integer distance right or left so that its right-angled vertex is

at $(0,0),$ then (if needed) rotated by $90,$ $180,$ or $270$ degrees so that

the other two vertices are in the first two quadrants, and then (if needed)

"flipped" (reflected) around the $y$ axis so that the leg in the first quadrant is

the shorter one.

So for the general case, let $A=(x_A,y_A),$ $B=(x_B,y_B),$ and $C=(0,0),$

where $x_A,$ $y_A,$ $x_B,$ and $y_B$ are all integers,

$x_A>0,$ $y_A>0,$ $x_B<0,$ and $y_B>0$ as in the figure.

The squares of the lengths of the two legs are then

$(AC)^2=x_A^2+y_A^2$ and $(BC)^2=x_B^2+y_B^2.$

Right away this tells us something about the possible lengths of sides:

the length of each leg is the square root of an integer.

But not all integers are sums of squares of integers,

so only some square roots of integers are possible side lengths.

To know if an integer $N$ is a sum of squares, find the prime factorization of $N.$

If no prime of the form $4k+3$ has an odd exponent in that factorization, $N$ is a

sum of two squares.

This is due to a theorem of Fermat as explained here.

Euler's proof of this theorem also gives some useful techniques to help find

possible pairs of squares.

For the given set of side lengths of a triangle, then,

let's determine whether $AC^2$ is the sum of two squares.

If it is not, we can stop right away; the triangle's vertices

cannot all have integer coordinates.

(For this step we just need the prime factorization of $AC^2.$

Let's examine leg $AC$ a little closer before we actually look for the two squares.)

The slope of the leg $AC$ is $y_A/x_A.$ Since $y_A$ and $x_A$ are both integers,

we can reduce this fraction to lowest terms, that is we can write

$$\frac{y_A}{x_A} = \frac qp$$

where $p$ and $q$ are integers that have no common divisor,

that is, $\gcd(p,q) = 1.$

This means $x_A=mp$ and $y_A=mq$ for some integer $m$

and $(p,q)$ is the point on the leg $AC$ with integer coordinates closest to $C.$

In the example in the figure, $(p,q)=(3,2).$

Since $(p,q)$ is on the leg $AC,$ the point $(-q,p)$ ($(-2,3)$ in the figure)

is on the leg $BC,$ perpendicular to $AC.$ Moreover, $(-q,p)$ is the point on $BC$

with integer coordinates that is closest to $(0,0).$

Any other point on the line $BC$ that has integer coordinates must have

coordinates that are just $(-q,p)$ scaled up by some integer factor.

In order for $B$ to be at integer coordinates, then, we must be able to write

$x_B=-nq$ and $y_B=np$ for some integer $n.$

So we can say this about the legs of the triangle: there exist positive integers

$m,$ $n,$ $p,$ and $q$ such that $\gcd(p,q) = 1,$

$$\begin{eqnarray}(AC)^2 &=& (mp)^2 + (mq)^2 &=& m^2(p^2 + q^2), \mbox{ and}\\

(BC)^2 &=& (np)^2 + (nq)^2 &=& n^2(p^2 + q^2).\end{eqnarray}$$

In the case of a triangle with sides $AC = 2\sqrt{13},$ $BC = 3\sqrt{13},$

and $AB = 13,$ like the one in the figure, we can then look for two squares of

positive integers whose sum is $(AC)^2 = 52.$ The only choice (apart from the

order in which we list the squares) is $52 = 6^2 + 4^2.$

This gives us $m=2,$ $p=3,$ and $q=2,$ as illustrated in the figure.

Now we need to check that we can find an integer $n$ such that

$(BC)^2 = n^2(p^2 + q^2).$ We find that $n=3,$ so we know we can place all vertices

of the triangle at integer coordinates, and moreover we have enough information

to find one such set of coordinates.

In other cases there is a pitfall we must avoid.

Suppose, for example, that $AC=5\sqrt{5},$ $BC=12\sqrt{5},$ and $AB=13\sqrt{5}.$

Then $(AC)^2 = 125 = 11^2 + 2^2,$ from which we get $m=1,$ $p=11,$ and $q=2.$

But we cannot find an integer $n$ such that $(BC)^2 = 720 = n^2(11^2 + 2^2).$

Yet we can place vertices of a triangle with these three side lengths

at integer coordinates: $A=(10,5),$ $B=(-12,24),$ and $C=(0,0).$

It matters which two squares we find whose sum is $(AC)^2.$

We could have written $(AC)^2 = 125 = 10^2 + 5^2,$

and then we would have $m=5,$ $p=2,$ and $q=1.$

We would then easily find that $(BC)^2 = 720 = 12^2(2^2 + 1^2).$

In order to find suitable pairs of squares, we first find the largest square

$m^2$ that divides $(AC)^2,$ so we can write $(AC)^2 = m^2 r$ where $r$

has no square factors.

In fact, if $(AC)^2$ is the sum of two squares, then the prime factorization

of $r$ has at most one factor of $2,$ at most one factor of

any prime of the form $4k+1,$ and no other factors, and so there are integers

$p$ and $q$ such that $r = p^2 + q^2.$

Moreover, for any values of $m',$ $p',$ and $q'$ that we could choose

so that $(AC)^2 = m'^2 (p'^2 + q'^2),$

we will find that $p^2 + q^2$ is a divisor of $p'^2 + q'^2$

and that the quotient is the square of an integer.

(This follows from facts used in counting the number of pairs of squares

with the desired sum.)

So if we can find an integer $n'$ such that $(BC)^2 = n'^2 (p'^2 + q'^2),$

we can find an integer $n$ such that $(BC)^2 = n^2 (p^2 + q^2).$

So if $(AC)^2$ is the sum of two squares, write $(AC)^2 = m^2 r$ where $m$ is an integer

and $r$ is an integer with no square factors,

and write $r = p^2 + q^2$ where $p$ and $q$ are integers.

If it is possible to place the vertices of a triangle with the desired side lengths

using only integer coordinates,

then $(BC)^2/(p^2 + q^2)$ will be the square of an integer $n,$ and we will

be able to write $(BC)^2 = n^2(p^2 + q^2)$ and find integer coordinates for all

vertices of the desired triangle.

But if $(BC)^2/(p^2 + q^2)$ is not the square of an integer,

then it is not possible to draw a triangle with the desired side lengths

using only integer coordinates for the vertices.