The use of the Pochhammer contour has nothing to do with the Argument Principle (as far as I know), and has everything to do with the multivaluedness of the logarithm.

The point of using the Pochhammer contour is to extend the defintion of the beta function

$$ B(\alpha, \beta) = \int_0^1 t^{\alpha-1} (1-t)^{\beta-1} {\rm d}x$$

to complex arguments, via analytic continuation.

This is because normally the integral above is valid for $\Re(\alpha), \Re(\beta)>0$.

Before getting tangled up with this loopy contour, let us recall a few things:

For complex $z,x$:

$$x^z := e^{z \log(x)} \quad \text{ and } \quad \log(x) := {\rm Log}(|x|) + 2\pi i k,\quad k \in \mathbb{Z},$$

where $\rm Log$ is the logarithm defined for real values.

Since the complex logarithm is multi-valued, if start from $x_0 \neq 0$ and we (anti-clockwise) loop around zero once with a path $\gamma$, we need get a factor of $+2\pi i$ to our logarithm. I will denote this by:

$$ \log(x_0) \leadsto \log(x_0) + 2\pi i . $$

This same mechanism gives us:

$$ (x_0)^z \leadsto e^{2\pi i z}(x_0)^z .$$

This explains the multivaluedness of complex exponentiation.

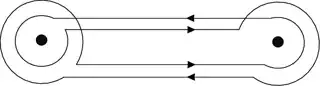

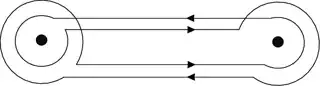

Let's now face the Pochhammer contour P (see below). The two black dots are $0$ and $1$. We can deform the straight lines so that they lie on the real line, so we obtain that $P = ABA^{-1}B^{-1}$, where $A$ is the loop starting at $1/2$ which goes once around $1$ anti-clockwise, and $B$ is the loop starting at $1/2$ which goes once around $0$ anti-clockwise.

Consider the integral over the Pochhammer contour

$$\int_P t^{\alpha-1} (1-t)^{\beta-1} {\rm d}x.$$

If $\Re(\alpha), \Re(\beta) >1$ then the integral vanishes along shrinking circles

around $1$ and $0$, since

$$|t^{\alpha-1} (1-t)^{\beta-1}|

= e^{(Re(\alpha)-1 ){\rm Log}(|t|)}

e^{(Re(\beta)-1) {\rm Log}(|1-t|)} \to 0 \quad \text{as} \quad t \to 0 \text{ or } 1.$$

Now, since the integrand is multi-valued as we explained above, as we turn around $0$ or $1$ we pick up an extra factor of $e^{2\pi i \alpha}$ or $e^{2 \pi i \beta}$ respectively (or possibly its inverse if we turn conterclockwise).

Thus the integrands change along different segments from 0 to 1, and they become:

$$t^{\alpha-1} (1-t)^{\beta-1}, \quad

t^{\alpha-1} e^{2 \pi i \beta} (1-t)^{\beta-1} \quad

e^{2 \pi i \alpha}t^{\alpha-1} e^{2 \pi i \beta}(1-t)^{\beta-1}, \quad

e^{2 \pi i \alpha}t^{\alpha-1}(1-t)^{\beta-1},$$

as we do $A$, then $B$, then $A^{-1}$ then $B^{-1}$, respectively.

Therefore we obtain that:

$$\int_P t^{\alpha-1} (1-t)^{\beta-1} {\rm d}x =

\int_0^1 t^{\alpha-1} (1-t)^{\beta-1} {\rm d}x +

e^{2 \pi i \beta} \int_1^0 t^{\alpha-1} (1-t)^{\beta-1} {\rm d}x +

e^{2 \pi i (\beta+\alpha)} \int_0^1 t^{\alpha-1} (1-t)^{\beta-1} {\rm d}x +

e^{2 \pi i \alpha} \int_1^0 t^{\alpha-1} (1-t)^{\beta-1} {\rm d}x

,$$

or in short:

$$\int_P t^{\alpha-1} (1-t)^{\beta-1} {\rm d}x = (1-e^{2 \pi i \alpha} )(1-e^{2 \pi i \beta} )B(\alpha, \beta). $$

This can be used to analytically extend the Beta function to the entire complex plane.