The proof goes back to at least Dedekind - being a special case of much more general results about conductor ideals. Here is a presentation bringing these concepts to the fore (but using nothing more than high-school algebra).

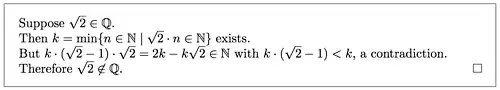

Theorem $\ $ Let $\;\rm n\in\mathbb N.\;$ Then $\;\rm r = \sqrt{n}\;$ is integral if rational.

Proof $\ $ Consider the set $\rm D$ of all the possible denominators $\rm d$ for $\rm r, \;$ i.e. $\;\rm D = \{\, d\in\mathbb Z \;:\: dr \in \mathbb Z\,\}$.

Note $\rm D$ is closed under subtraction: $\rm\, d,e \in D\, \Rightarrow\, dr,\,er\in\mathbb Z \,\Rightarrow\, (d-e)\:r = dr - er \in\mathbb Z.\;$

Further $\rm d\in D \,\Rightarrow\, dr\in D\,$ since $\rm\, (dr)r = dn\in\mathbb Z \;$ by $\;\rm r^2 = n\in\mathbb Z.\;$ Therefore, invoking the Lemma below,

with $\rm d $ the least positive element in $\rm D,$ we infer that $\;\rm d\,|\,dr \;$ in $\mathbb Z,\;$ i.e. $\rm\ r = (dr)/d \in\mathbb Z.\quad$ QED

Lemma $\ $ Suppose $\;\rm D\subset\mathbb Z \;$ is closed under subtraction and that $\rm D$ contains a nonzero element.

Then $\rm D \:$ has a positive element and the least positive element of $\rm D$ divides every element of $\rm D\:$.

Proof $\rm\,\ \ 0 \ne d\in D \,\Rightarrow\, d-d = 0\in D\,\Rightarrow\, 0-d = -d\in D.\, $ Hence $\rm D$ contains a positive element. Let $\rm d$ be the least positive element in $\rm D$. Since $\rm\: d\,|\,n \!\iff\! d\,|\,{-}n,\,$ if $\rm\, c\in D$ is not divisible by $\rm d$ then we

may assume that $\rm c$ is positive, and the least such element. But $\rm\, c-d\,$ is a positive element of $\rm D$ not divisible by $\rm d$

and smaller than $\rm c$, contra leastness of $\rm c$. So $\rm d$ divides every element of $\rm D.\ $ QED

Remark $ $ The theorem's proof exploits the fact that the denominator ideal $\rm D$ has the special property that it is closed under multiplication by $\rm\: r\:.\ $ The fundamental role that this property plays becomes clearer when one learns about Dedekind's notion of a conductor ideal. Employing such yields a trivial one-line proof of the generalization that a Dedekind domain is integrally closed since conductor ideals are invertible so cancellable. This viewpoint serves to generalize and unify all of the ad-hoc proofs of this class of results - esp. those proofs that proceed essentially by descent on denominators. This conductor-based structural viewpoint is not as well known as it should be - e.g. even some famous number theorists have overlooked this. See my post here for further details.