I did the following analysis for $2\times2$ real idempotent (i.e. $A^2=A$) matrices: $$ \begin{bmatrix}a&b\\c&d\end{bmatrix}^2=\begin{bmatrix}a^2+bc&(a+d)b\\(a+d)c&bc+d^2\end{bmatrix}=\begin{bmatrix}a&b\\c&d\end{bmatrix} $$ So in particular we have $(a+d)c=c$ and $(a+d)b=b$ so if either $b$ or $c$ is nonzero we have $a+d=1$. We also see that $a$ and $d$ both satisfy the equation $x^2+bc=x\iff x^2-x+bc=0$ which is a quadratic equation having solutions $$ x=\frac{1\pm\sqrt{1-4bc}}{2}=0.5\pm\sqrt{0.25-bc} $$ But this is only possible if $bc\leq 0.25$ for otherwise the above expression is not real. This gives us the following cases:

CASE 1: If $b,c=0$ we have $x\in\{0,1\}$ and since $a+d=1$ is unnecessary we have four possibilities: $(a,d)\in\{(0,0),(1,0),(0,1),(1,1)\}$.

CASE 2: If $bc=0.25$ we have $x=0.5$ so $a=d=0.5$.

CASE 3: If $bc<0.25$ yet $(b,c)\neq(0,0)$ we have $x\in L=\{0.5-\sqrt{0.25-bc},0.5+\sqrt{0.25-bc}\}$ and to have $a+d=1$ we must have $\{a,d\}=L$ so that if $a$ is one solution, then $d$ is forced to be the other solution. Or the other way around.

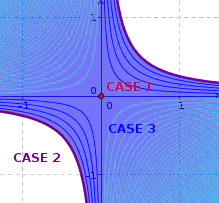

The cases can be illustrated via the following diagram graphing the hyperbola $xy=0.25$ corresponding to CASE 2, the area $xy<0.25$ corresponding to CASE 3, and the point $(0.0)$ corresponding to CASE 1:

The blue bands show the graphs of $xy=k$ for $k=0.05$ to $0.20$ and the cyan bands show $xy=k$ for $k=-0.05,-0.10,...$ For instance one could choose $(b,c)=(3.75,-1)$ so that $\sqrt{0.25-bc}=2$ thus rendering $x=0.5\pm 2=-1.5$ and $2.5$ and form the matrix $$ A=\begin{bmatrix}-1.5&3.75\\-1&2.5\end{bmatrix} $$ which will then be idempotent, as an example of CASE 3.

QUESTIONs:

- Can similar descriptions be derived for $3\times 3$ matrices?

- Is this a well known description of idempotent $2\times 2$ matrices?