According to Table 1 of following paper by GK Das et al (2006),

$\hspace0.3in$Efficient algorithm for placing a given number of base stations to cover a convex region

the minimum radius for 23 circles to over a unit square is at most $0.14124482238793135951$. Since this is smaller than $\displaystyle\;\frac{\sqrt{2}}{10}$, at most 23 circles is enough.

I have no idea how the configuration for 23 circles look like. However, following is a

page

which has the configuration of best known covering of a square by up to $12$ equal circles.

As your can see, the configuration doesn't seem to follow any obvious pattern. It is highly

unlikely that $n^{*}$ has any simple formula.

Update

The configurations in Table 1 are computed in a research notes (Ref 15 in GK Das' paper)

$\hspace0.3in$Covering a square with up to 30 equal circles by K.J. Nurmela, P.R.J. Ostergard

An online copy (in postscript) is available here. It has pictures for configuration up to 30 circles.

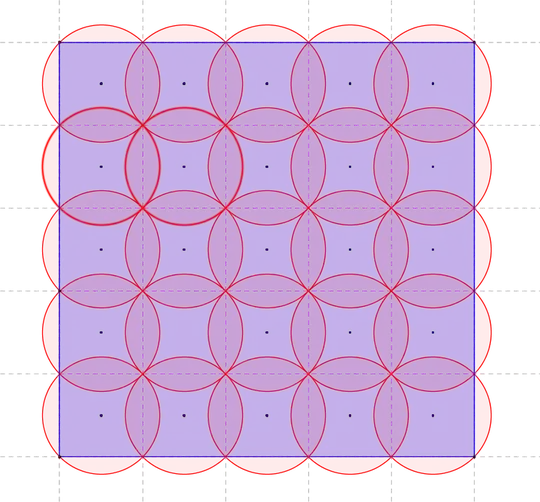

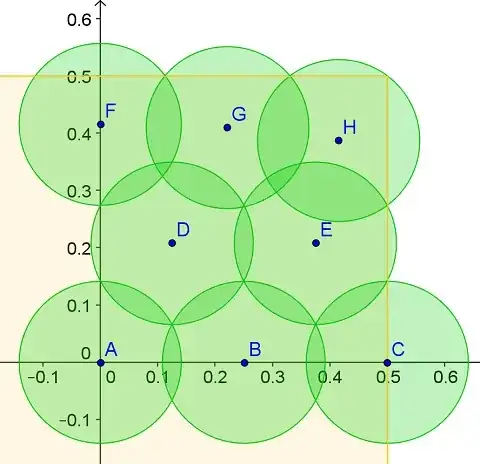

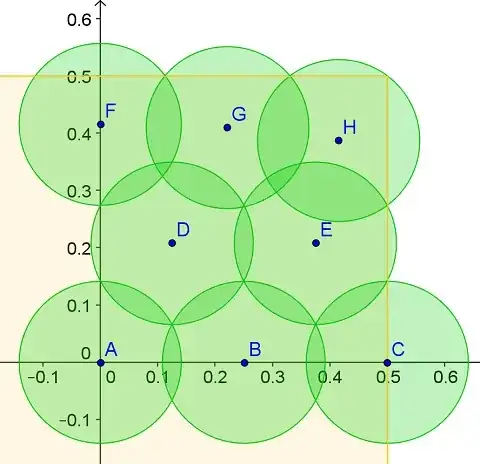

Based on above paper, following is one way to cover the unit square with 23 circles

of radius $\frac{\sqrt{2}}{10}$.

For simplicity of presentation, we will center the unit square at the origin and

only show the $8$ circles on the first quadrant.

In this configuration, the centers of the circles are positioned at:

$$\begin{array}{|c:l|}

\hline

\text{eg.} & (x,y)\\

\hline

A, B, C & (0,0), (\pm 0.25,0), (\pm 0.5,0)\\

D, E & (\pm 0.125,\pm 0.20756513901392), (\pm 0.375,\pm0.20756513901392)\\

F & (0, \pm 0.41513027802785)\\

G & (\pm 0.22172066050239,\pm 0.40940831933773)\\

H & (\pm 0.41515845958082,\pm 0.38685446089527)\\

\hline

\end{array}$$

The centers of the middle 3 layers (i.e those in the same layers as $A,B,C,D,E$) are forming a triangular lattice elongated in the vertical direction.