First of all, I am aware of the question in How to embed Klein Bottle into $R^4$ , which was inconclusive. Anyway, I've made some progress, but I still have a question.

I am using Do Carmo's Riemannian Geometry, and struggling to solve a problem.

The problem is:

Show that the mapping $G:\mathbb{R}^2\to\mathbb{R}^4$ given by

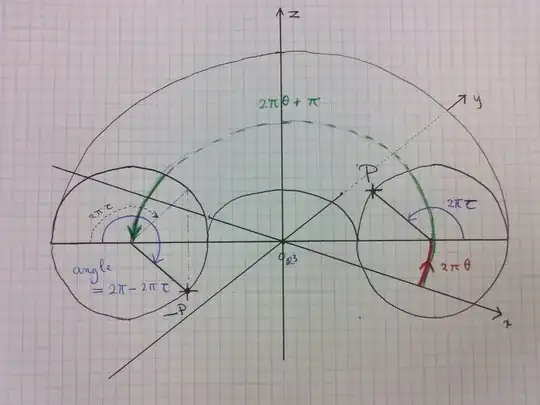

$$G(x,y)=((r\cos (2\pi y)+a)\cos (4\pi x),(r\cos (2\pi y)+a)\sin (4\pi x),r\sin (2\pi y)\cos (2\pi x),r\sin (2\pi y)\sin (2\pi x)))$$

induces an embedding of the Klein bottle into $\mathbb{R}^4$ (It is a slightly different function from the one in the book, but works in the same way).

First of all, it's not hard to see that $$G(x+n,y+m)=G(x,y)\text{ whenever }m,n\in\mathbb{Z}.$$ Therefore, this mapping is well-defined over the torus $\mathbb{T}^2$. What I need now is to show that $G(-x,-y)=G(A(x,y))=G(x,y)$, where $A$ is the antipode mapping. If this were true, then the mapping G would be well-defined over the Klein Bottle, but it's obvious that this is false.

Am I working wrong here somewhere?

Consider the embedding

Consider the embedding

But he uses the Antipode mapping $A$ and the isomorphism group ${ Id, A}$ to obtain the Klein Bottle from the Torus, and it wasn't working

– Marra Apr 18 '14 at 15:34