Is there a function whose limit does not exist as x approaches infinity but the integral of that function from negative infinity to positive infinity is equal to 1?

-

But the limit of that functions as x goes to infinity is zero – user138288 Mar 26 '14 at 23:13

-

Wha--?! You already said the limit doesn't exist. You can't have it both ways! – MPW Mar 26 '14 at 23:25

-

$f(x) = \sqrt{\frac{2}{\pi}} \sin(x^{2}) $ – Random Variable Mar 26 '14 at 23:33

5 Answers

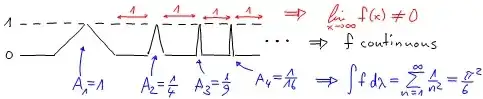

I think the general principle behind @heropup's example is the following rather simple idea:

That idea even can be exhausted to create a smooth function whos integral equals one though its limit at infinity does not exist (pasting smooth bump functions rather than merely continuous peeks).

- 17,045

An example of a continuous and differentiable function $f : \mathbb R \to \mathbb R^+$ such that $\lim_{x \to \infty} f(x)$ does not exist, but $\int_{x=0}^\infty f(x) \, dx < \infty$, is $$f(x) = \sum_{k=1}^\infty \frac{1}{1+k^4 (x-k^2)^2}.$$ Clearly, $0 < f(x) < \infty$ for all $x$ (convergence is assured by a simple comparison test). It is intuitive that $\displaystyle \lim_{x \to \infty} f(x)$ does not exist: details of a formal proof is left to the reader. The idea is that $f(n^2) > 1$ for each $n \in \mathbb Z^+$, but $f(x) \to 0$ for sufficiently large $x$ not "close" to a square. Meanwhile, the integral is bounded above by $$\int_{x=0}^\infty \sum_{k=1}^\infty \frac{dx}{1+k^4(x-k^2)^2} = \sum_{k=1}^\infty \frac{\pi + 2 \tan^{-1} k^4}{2k^2} < \pi \sum_{k=1}^\infty \frac{1}{k^2} = \frac{\pi^3}{6}.$$

- 143,828

-

No. If $\lim_{x \to \infty} f(x) = L = 0$, then for any $\epsilon > 0$, there would exist $N$ such that $|f(x)| < \epsilon$ whenever $x > N$. But no such $N$ exists; for example, $$f(\lceil N \rceil^2) = \sum_{k=1}^\infty \frac{1}{1+k^4(\lceil N \rceil^2 - k^2)^2} > \frac{1}{1+\lceil N \rceil^4 (\lceil N \rceil^2 - \lceil N \rceil^2)^2} = 1.$$ – heropup Mar 27 '14 at 04:53

-

Yes, take your favorite continuous function with the required integral. Then change $f(n)$ to $1$ for all $n \in \Bbb N$ Changing those points does not change the integral. For a specific example, $$f(x)=\begin {cases} 0& x \le 0 \\1&x \in \Bbb N \\ \exp(-x)& x \gt 0 \wedge x \not \in \Bbb N \end {cases}$$

- 383,099

-

Sorry, I'm not really sure what you mean by that. Can you give an example? – user138288 Mar 26 '14 at 23:16

-

Isn't the integral of exp(-x) from negative infinity to positive infinity non existent? I don't think the integral is 1, is it? – user138288 Mar 27 '14 at 01:13

-

-

Thanks, but didn't you say to start with a continuous function whose integral from negative infinity to positive infinity is 1? That's where I'm confused because exp(-x) doesn't work there. – user138288 Mar 27 '14 at 01:25

-

That is true. You can bend it a bit to make it continuous. The real point is that it is easy to destroy the limit at $+\infty$ – Ross Millikan Mar 27 '14 at 02:42

If you allow discontinuities, then you could take your favorite function with integral 1, and add discontinuities at each natural number. The integral doesn't change since the set of discontinuities has measure zero, but the limit doesn't exist.

- 1,489

-

Can you give an example of a function that has integral from negative infinity to positive infinity equal to 1? I'm being dumb and can't seem to get that part – user138288 Mar 27 '14 at 01:24

Let $f$ be the function given by $$ f(t)=\begin{cases}2^{n+1}(t-n),&\ t\in[n,n+1/2^{n+1})\\ 3-2^{n+1}(t-n),&\ t\in[n+1/2^{n+1},n+1/2^n]\\ 0,&\ \text{ otherwise }\end{cases} $$

(if you don't want to bother with the computations, at the beginning of each interval it consists of a triangle of height 2 and base $1/2^n$, so its area is $1/2^n$. Over the rest of each interval, the function is zero. The integral will be the sum of the areas of these triangles, which add to one)

This function is continuous. It's limit at infinity does not exist, because it achieves all values from zero to two between any two consecutive integers. And $$ \int_0^\infty f(t)dt=\sum_{n=1}^\infty\int_n^{n+1}f(t)dt=\sum_{n=1}^\infty\int_0^1f(t+n)dt\\ =\sum_{n=1}^\infty\int_0^{1/2^{n+1}}2^{n+1}t\,dt+\int_{1/2^{n+1}}^{1/2^{n}}(3-2^{n+1}t)\,dt\\ =\sum_{n=1}^\infty\frac{2^{n}}{2^{2n+2}}+\frac3{2^{n+1}}-2^{n}\left(\frac1{2^{2n}}-\frac1{2^{2n+2}} \right)\\ =\sum_{n=1}^\infty\frac1{2^n}=1 $$

If you want to give up absolute convergence of the integral, you can even get $f$ to be infinitely differentiable, as in Random Variable's example: $f(x)=\sqrt{2/\pi}\,\sin(t^2)$ (if over the whole line, otherwise one multiplies by 2).

- 217,281

-

What do you precisely mean by absolute convergence of the integral? – freishahiri Mar 27 '14 at 03:26

-

An integral $\int_{0}^\infty f$ is absolutely convergent if $\int_0^\infty|f|<\infty$. – Martin Argerami Mar 27 '14 at 03:54

-

So you mean absolutely integrable rather than absolutely convergent - note, the subject is integrals not improper integrals (I guess?) – freishahiri Mar 27 '14 at 04:09

-

Besides regarding you're last claim: There are smooth functions which are properly Lebesgue (absolutely if u want) integrable whos limit at infinity does not exist. So all desired properties together :) – freishahiri Mar 27 '14 at 04:13

-

Yes, one can make the bumps smooth and use the same idea. In any case, the point of my answer was to challenge the common "intuition" that for an improper integral to converge the function should go to zero. – Martin Argerami Mar 27 '14 at 04:21