As we deal with arbitrary functions $f \colon A \to B$ and $g \colon B \to A$, there is nothing special to be got by taking $\lvert A \rvert = \lvert B \rvert = n$, so we'll answer the question more generally: Let's say we have $\lvert A \rvert = m$ men, and $\lvert B \rvert = w$ women. This adds no real difficulty to the calculations, and instead makes some expressions clearer. For your case, just set $m = w = n$.

The random model we assume throughout is that we pick any of the $w^m m^w$ pairs of functions $(f, g)$ with equal probability.

We will prove below that, under this random model,

the expected number of fixed points of $f \circ g$ or $g \circ f$, or in other words, the expected number of pairs of men and women who like each other, is $1$, and more generally,

for any $k$, the probability that this number of fixed points is exactly $k$ is a quantity that we can calculate exactly, and approaches $\dfrac{1}{k!e}$ as $m, w \to \infty$. In other words, the distribution of the number of mutually liking pairs approaches a Poisson distribution with mean $1$.

- "If I like someone, what is the probability that they like me back?"

Answer: $\dfrac1m$ if I'm a man, $\dfrac1w$ if I'm a woman.

For any $f\colon A \to B$ and any $a \in A$, if $f(a) = b \in B$, then the probability over random functions $g\colon B\to A$ that $g(b) = a$ is exactly $\dfrac1m$, as $g(b)$ takes on all $\left\vert{A}\right\vert = m$ values with equal probability. And as the probability is the same for each specific $f$, it remains the same when $f$ too is chosen at random.

Similarly for the women.

- "What is the expected number of men who are liked back by the women they like?"

Answer: $1$.

This is by linearity of expectation: for any $f$, we have

$$\operatorname{E}\left[\#\{a: g(f(a)) = a\}\right] = \sum_{a \in A} \Pr(g(f(a)) = m \frac1m = 1.$$

And as the expectation is the same for each individual $f$, it is also the same when $f$ itself is picked at random.

- "What is the expected number of women who are liked back by the men they like?"

Answer: $1$.

By symmetry / a similar calcuation.

- "What is the expected number of pairs of (men, women) who like each other?"

Answer: $1$.

The number of mutually liking pairs is of course the same as the either of the two numbers just previously considered.

So this actually answers your original question: the expected number of pairs $(a, b)$ such that $f(a) = b$ and $g(b) = a$ is exactly $1$.

It remains to answer the question you "reduced" it to (which as we will see is not exactly a reduction), about the number of pairs of functions $f \colon A \to B$ and $g \colon B \to A$ such that $g \circ f$ has no fixed points. Let's sidle up to it by inches.

- "For a given set of $k$ men, what is the probability that they are all liked back by the women they like?"

Answer: $\dfrac{\binom{w}{k}k!}{w^k m^k} = \dfrac{w^{\underline k}}{w^k m^k}$.

Given $f$ and $a_1, a_2, \dots, a_k$, what is the probability that $g(f(a_i)) = a_i$ for all $1 \le i \le k$? This probability depends on $f$. Clearly a necessary condition that all the $a_i$'s like distinct women: if two of them like the same woman, there is no way they can both be liked back. But for any $f$ where this necessary condition holds, then the events of each of them being liked back are independent; each of the men is liked back with probability $1/m$, giving probability $\dfrac1{m^k}$ that they are all liked back.

The number of functions $f$ satisfying this distinctness condition is $\displaystyle \binom{w}{k}k! w^{m-k}$. Thus the probability when taken over all functions $f$ is

$$\frac{\frac{1}{m^k} \cdot \binom{w}{k}k! w^{m-k} + 0 \cdot \text{(the rest)}}{w^m} = \frac{\binom{w}{k}k!}{m^k w^k}$$

and so the number of such pairs of functions $(f, g)$ is $w^{m-k}m^{w-k}\binom{w}{k}k!$.

(We could also have calculated this directly: the function $f$ on the $a_i$'s can be picked in $\binom{w}{k}k!$ ways, on the other $a$'s in $w^{m-k}$ ways, and $g$ in $m^{w-k}$ ways.)

We can also use the falling factorial notation: $w^{\underline k} = \binom{w}{k}k!$.

Finally we can answer the question:

- "What is the probability that no one is liked back?"

That is, what is the probability that $g \circ f$ has no fixed points? Let the set $L \subseteq A$ denote the set of fixed points of $g \circ f$: the set of lucky men who are liked back. We have calculated, in the previous question, the probability that $A_k \subseteq L$, for any particular subset $A_k$ of $A$ having size $k$. Thus, by the inclusion-exclusion principle,

$$\begin{align}

\Pr(L = \emptyset)

&= \Pr(\emptyset \subseteq L) - \binom{m}{1}\Pr(A_1 \subseteq L) + \binom{m}{2}\Pr(A_2 \subseteq L) - \binom{m}{3}\Pr(A_3 \subseteq L) + \dots \\

&= \sum_{k=0}^m (-1)^k \binom{m}{k}\binom{w}{k} k! m^{-k}w^{-k}

\end{align}$$

Using the falling factorial notation, the above can also be written as

$$P_{m, w, 0} = \sum_{k=0}^{\infty} \frac{m^{\underline k}}{m^k} \frac{w^{\underline k}}{w^k} \frac{(-1)^k}{k!}$$

I changed the upper limit of the sum to $\infty$ instead of $m$, to highlight that the expression is symmetric in $m$ and $w$: note that when $k > m$ we have $m^{\underline k} = 0$, and when $k > w$ we have $w^{\underline k} = 0$, so the terms in the sum are nonzero only up to $k = \min(m, w)$.

For the particular case when $m = w = n$, the number of pairs of functions $(f, g)$ such that $g \circ f$ has no fixed points is

$$\begin{align}

T_n

&= n^{2n} P_{n,n,0} \\

&= n^{2n} \sum_{k=0}^n (-1)^k \binom{n}{k}^2 k! n^{-2k} \\

&= n^{2n} \sum_{k=0}^n \left(\frac{n^{\underline k}}{n^k}\right)^2 \frac{(-1)^k}{k!}

\end{align}$$

This number $T_n$, for $n = 0, 1, 2, \dots$, takes the values

$$1, 0, 2, 156, 16920, 2764880, 650696400, 210105425628, 89425255439744, 48588905856409920, 32845298636854828800, 27047610425293718239100, 26664178085975252011318272, 31009985808408471580603417296, 42017027730087624384021945067520, 65618911142809749231767185516069500, \dots$$

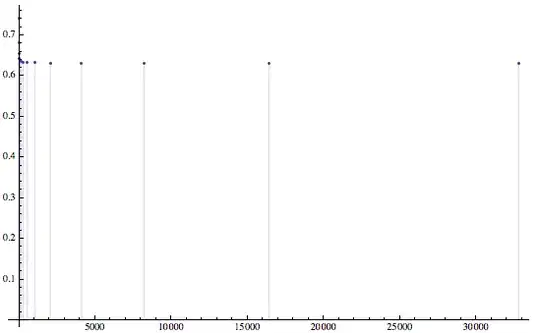

and is surprisingly not in OEIS, nor are the corresponding probabilities $P_{n,n,0} = \dfrac{T_n}{n^{2n}}$ which are

$$1, 0, \frac18, \frac{52}{243}, \frac{2215}{8192}, \frac{552976}{1953125}, \dots$$

$$\approx 1, 0, 0.125, 0.214, 0.258, 0.283, 0.299, 0.310, 0.318, 0.324, 0.328, 0.332, 0.335, 0.338, 0.340, 0.342, \dots$$

However, we will prove below that $P_{n, n, 0}$ approaches $\dfrac{1}{e} \approx 0.367879\dots$ as $n \to \infty$. Note that even before the proof, we can find this plausible, for two reasons:

- when the factor $\frac{n^{\underline k}}{n^k}$ (squared) which is close to $1$ is removed, the sum $\sum_{k=0}^{n} \frac{(-1)^k}{k!}$ does indeed converge to $e^{-1}$ as $n \to \infty$ (this will be how we prove it), and

- each $a \in A$ is not a fixed point with probability $1 - \frac1n$, so the independence approximation (treating these events as independent even though they are not) gives the probability of no fixed points to be $\left(1 - \frac1n \right)^n \to e^{-1}$, and perhaps this independence approximation gets better for large $n$.

Extending the above we can also answer

- "What is the probability that exactly $k$ men are liked back?"

Your expression for the number of such pairs of functions (on which hinges calling the previous problem a reduction) was $\displaystyle \binom{n}{k}^2 k! T_{n-k}$, meant to count the number of functions $(f, g)$ such that $k$ pairs are mutually liking and there are no fixed points on the remaing $n-k$ men and women. But this is not correct, as (for instance) the function on the remaining $m-k$ elements of $A$ is not constrained to take on values from the remaining $w-k$ elements of $B$ alone (it can also take values from the same $k$ elements already picked).

The right expression is given by the inclusion-exclusion principle: given a particular set $A_k$ of $k$ men, the probability that these are exactly the men liked back is

$$\begin{align}

\Pr(L = A_k)

&= \Pr(A_k \subseteq L) - \binom{m-k}{1}\Pr(A_{k+1} \subseteq L) + \binom{m-k}{2}\Pr(A_{k+2} \subseteq L) - \dots \\

&= \sum_{r=0}^{m-k} (-1)^r \binom{m-k}{r} \binom{w}{k+r}\frac{(k+r)!}{m^{k+r}w^{k+r}} \\

&= \sum_{l=k}^m (-1)^{l-k} \binom{m-k}{l-k} \binom{w}{l} \frac{l!}{m^l w^l}

\end{align}$$

and the probability got by choosing all sets of size $k$ is $\displaystyle \binom{m}{k}$ times that:

$$\begin{align}

P_{m, w, k}

&= \sum_{l=k}^m (-1)^{l-k} \binom{m}{k} \binom{m-k}{l-k} \binom{w}{l}\frac{l!}{m^l w^l} \\

&= \sum_{l=k}^m (-1)^{l-k} \binom{l}{k} \binom{m}{l} \binom{w}{l} \frac{l!}{m^l w^l} \\

&= \frac{1}{k!} \sum_{l=k}^m \frac{m^{\underline l}}{m^l} \frac{w^{\underline l}}{w^l} \frac{(-1)^{l-k}}{(l-k)!} \\

&= \frac{1}{k!} \sum_{r=0}^{\infty} \frac{m^{\underline {k+r}}}{m^{k+r}} \frac{w^{\underline {k+r}}}{w^{k+r}} \frac{(-1)^r}{r!}

\end{align}$$

(again we've changed the upper limit of the sum, with no change in value).

Note that when $k=0$, we recover our earlier expression for $P_{m, w, 0}$. We will prove below that $P_{m, w, k} \to \frac{1}{k!e}$ as $m, w \to \infty$.

- "What is the expected number of men who are liked back?"

We already answered this earlier (it's $1$), but using the above, it is also equal to

$$\begin{align}

\sum_{k=0}^m k P_{m, w, k}

&= \sum_{k=0}^m k \sum_{r=k}^{m} (-1)^{r-k} \binom{r}{k} \binom{m}{r} \binom{w}{r}\frac{r!}{m^rw^r} \\

&= \sum_{r=0}^m \binom{m}{r}\binom{w}{r}\frac{r!}{m^rw^r} (-1)^r \sum_{k=0}^r k\binom{r}{k} (-1)^{k}

\\ &= 1

\end{align}$$

(as the inner sum is nonzero only for $r=0$), as expected.

Finally, the promised proof about $P_{m, w, k}$. Suppose that $m$ and $w$ both go to infinity, in any which way — the relative rates don't matter. We can imagine them given by a sequence $(m_i, w_i)$, with the only property being needed that $m_i \to \infty$ and $w_i \to \infty$ as $i \to \infty$.

Then, for every fixed $k$ and $r$, we have $\displaystyle \frac{m_i^{\underline {k+r}}}{m_i^{k+r}} \frac{w_i^{\underline {k+r}}}{w_i^{k+r}} \to 1$ as $i \to \infty$ (and moreover is less than $1$ in absolute value), so by the dominated convergence theorem for series (see here for instance; idea via user Etienne here), we have

$$\begin{align}

\lim_{i \to \infty} P_{m_i, w_i, k}

&= \lim_{i \to \infty} \frac{1}{k!} \sum_{r=0}^{\infty} \frac{m_i^{\underline {k+r}}}{m^{k+r}} \frac{w_i^{\underline {k+r}}}{w^{k+r}} \frac{(-1)^r}{r!} \\

&= \frac{1}{k!} \sum_{r=0}^{\infty} \frac{(-1)^r}{r!} \\

&= \frac{1}{k!e}

\end{align}$$

which proves our claims about the limiting distribution.

Some data: For $0 \le n \le 7$, below is the number $n^{2n}P_{n, n, k}$ of pairs of functions $f,g$ for $m=w=n$, such that $f \circ g$ has exactly $k$ fixed points.

0 {0: 1}

1 {0: 0, 1: 1}

2 {0: 2, 1: 12, 2: 2}

3 {0: 156, 1: 423, 2: 144, 3: 6}

4 {0: 16920, 1: 33184, 2: 13968, 3: 1440, 4: 24}

5 {0: 2764880, 1: 4581225, 2: 2088800, 3: 316200, 4: 14400, 5: 120}

6 {0: 650696400, 1: 973830816, 2: 460350000, 3: 85521600, 4: 6231600, 5: 151200, 6: 720}

7 {0: 210105425628, 1: 293840040823, 2: 141537806928, 3: 29771976150, 4: 2849330400, 5: 116794440, 6: 1693440, 7: 5040}

Next, (some of) the corresponding probabilities $P_{n, n, k}$:

1 {0: 0.000, 1: 1.00}

2 {0: 0.125, 1: 0.750, 2: 0.125}

3 {0: 0.214, 1: 0.580, 2: 0.198, 3: 0.00823}

4 {0: 0.258, 1: 0.506, 2: 0.213, 3: 0.0220, 4: 0.000366}

5 {0: 0.283, 1: 0.469, 2: 0.214, 3: 0.0324, 4: 0.00147, 5: 0.0000123}

6 {0: 0.299, 1: 0.447, 2: 0.211, 3: 0.0393, 4: 0.00286, 5: 0.0000695, 6: 3.31e-7}

7 {0: 0.310, 1: 0.433, 2: 0.209, 3: 0.0439, 4: 0.00420, 5: 0.000172, 6: 2.50e-6, 7: 7.43e-9}

8 {0: 0.318, 1: 0.423, 2: 0.206, 3: 0.0471, 4: 0.00538, 5: 0.000303, 6: 7.70e-6, 7: 7.22e-8, 8: 1.43e-10}

9 {0: 0.324, 1: 0.416, 2: 0.204, 3: 0.0494, 4: 0.00638, 5: 0.000444, 6: 0.0000160, 7: 2.72e-7, 8: 1.74e-9, 9: 2.42e-12}

10 {0: 0.328, 1: 0.410, 2: 0.202, 3: 0.0511, 4: 0.00723, 5: 0.000586, 6: 0.0000269, 7: 6.62e-7, 8: 7.84e-9, 9: 3.59e-11}

100 {0: 0.364, 1: 0.372, 2: 0.186, 3: 0.0607, 4: 0.0146, 5: 0.00273, 6: 0.000419, 7: 0.0000539, 8: 5.94e-6, 9: 5.69e-7, ...}

1000 {0: 0.368, 1: 0.368, 2: 0.184, 3: 0.0613, 4: 0.0153, 5: 0.00303, 6: 0.000501, 7: 0.0000709, 8: 8.76e-6, 9: 9.59e-7, ...}

and for $n = 10000$:

10000 {0: 0.36784, 1: 0.36792, 2: 0.18396, 3: 0.061307, 4: 0.015321, 5: 0.0030623, 6: 0.00050997, 7: 0.000072781, 8: 9.0867e-6, 9: 1.0082e-6, ...}

Contrast this with the actual Poisson distribution $\frac{1}{k!e}$:

{0: 0.36788, 1: 0.36788, 2: 0.18394, 3: 0.061313, 4: 0.015328, 5: 0.0030657, 6: 0.00051094, 7: 0.000072992, 8: 9.1240e-6, 9: 1.0138e-6, ...}

So we can see that convergence is rather slow.