Addition, subtraction, and XOR are all equivalent in this case:

A quick note: this a follow up to Ross Millikan as well as a couple other comments to bring together a few of the ideas and make it more accessible to non-mathematicians.

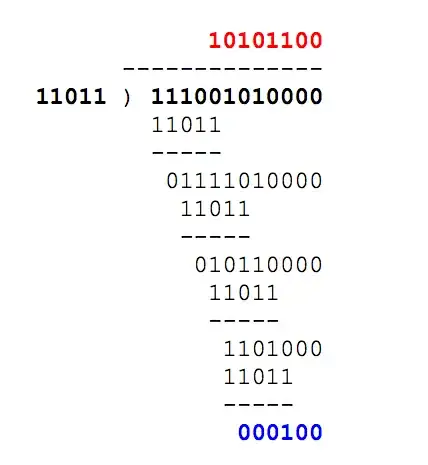

- as Jyrki Lahtonen noted, the above style of "binary division" is likely from a computer science method of error correction called Cyclic Redundancy Check (CRC).

- this is not normal binary division. As mark has noted the "subtractions" also appear to be xor operations.

- I'm not 100% sure if there is a proper mathematical name for this, but in computer science you will see stuff like: binary polynomial division over a finite field, etc. (In CRC we are actually interested in the modulo/remainder not the quotient)

The finite field part is the important point. In each subtraction operation that makes up the "division," the subtraction is over the finite field of 0 and 1 for that one binary digit.

For integer values over this finite-field size (0 and 1 are the only possibilities) addition, subtraction, and XOR are all equivalent functions. For most inputs this is intuitive. However, for 1 + 1 and 0 - 1, given the finite field it is necessary to loop around to the other side of the finite-field:

1 + 0 = 1

1 - 0 = 1

1 XOR 0 = 1

1 + 1 = 2 (or 10 with the carry in binary) but over the finite field this one greater than the largest value in the field maps back to the first value value in the field so zero

1 - 1 = 0

1 XOR 1 = 0

0 + 1 = 1

0 - 1 = -1 but again since we are one less than the minimum value in the finite field this maps to the largest value in that field so one

0 XOR 1 = 1

Just like mathematicians, computer science people arbitrarily define certain operations in certain contexts for their usefulness, or to enable further level of abstraction: Think of the "addition" or "multiplication" operations in Elliptical Curve Cryptography.

With that in mind, in the context of CRC, it is perfectly legitimate to call this "binary division"