First, notice that Fraleigh does not claim that $\phi$ is a map of $G$ onto $G'$, as you said. He only claims that it is onto $\phi[G]$. This is a weaker statement because $\phi[G]$ may be a proper subset of $G'$.

1.

I don't think a long explanation will make this any clearer than my comment above, that any function is onto its own range because that's what the range is. But what the heck. $\phi[G]$ is defined as $$\phi[G] = \{ \phi(x)\mid x\in G\}$$ which is actually shorthand for $$\phi[G] = \{ y\mid\text{there is some $x\in G$ such that $\phi(x)=y$} \}.$$ We want to show that $\phi$ is onto $\phi[G]$. This means we want to show that every $y$ in $\phi[G]$ is the image of some $x\in G$ under the mapping $\phi$.

That is for each $y\in \phi[G]$, we want to show that there is some $x\in G$ such that $\phi(x) = y$.

But that is exactly the definition of $\phi[G]$ that I quoted above.

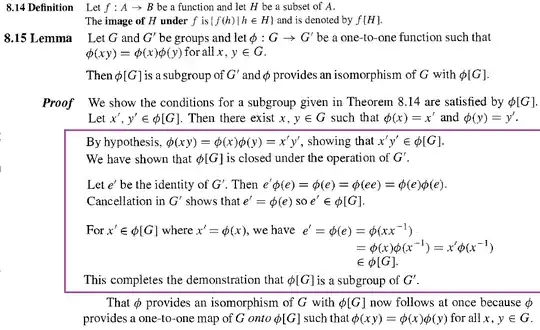

2. Fraleigh supposes that $\phi(xy)=\phi(x)\phi(y)$. This is the important property of a homomorphism. A homomorphism is just a mapping between two groups that satisfies that condition. He has two groups, $G$ and $G'$, and $\phi$ is a mapping between them that by hypothesis satisfies the condition. So $\phi$ is a homomorphism of $G$ into $G'$.

3. This is a matter of opinion. But I did not find it unclear.

4. I don't know what you mean by "picture". The point of the theorem is that a one-to-one homomorphism from $G$ to $G'$ is like locating a copy of $G$ inside of $G'$. Does that help?

If you are still confused, I suggest you try some small examples to see how it works. For example, let $G = Z_2, G' = Z_8,$ and $\phi(x) = 4x$. Then $\phi[G] = \{ 0, 4 \}$. And under mod-8 addition, $\{0 , 4\}$ is indeed a subgroup of $Z_8$, one that behaves just like $Z_2$.

Or consider $G=Z_4$ again, and $G'$ is the nonzero complex numbers under multiplication. Take $\phi(n) = i^n$. Then you can verify that $\phi(a + b) = \phi(a)\cdot \phi(b)$. $\phi[G] = \{ i, -i, -1, 1 \}$, and we have found a copy of $Z_4$ inside the complex numbers.